A research team led by a scientist at the University of California, Riverside, has found that brains treated with certain drugs within a few days of an injury have a dramatically reduced risk of developing epilepsy later in life.

The development of epilepsy is a major clinical complication after brain injury, and the disease can often take years to appear.

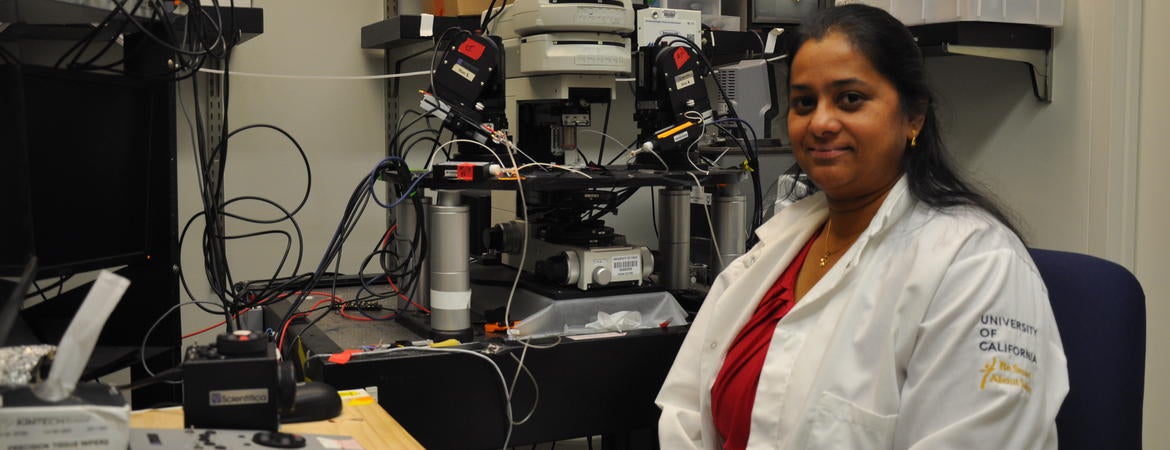

“Working on rats, whose immune response system models that of humans, we identified that after brain injury a certain immune system receptor makes the brain more excitable, which promotes development of epilepsy,” said Viji Santhakumar, an associate professor of molecular, cell, and systems biology at UC Riverside and the lead author of the study that appears in the Annals of Neurobiology. “If this receptor can be suppressed, preferably within a day after injury, the future development of epilepsy can be reduced if not entirely prevented.”

The receptor in question is the Toll-like receptor 4, or TLR4, an innate immune receptor. Following a brain injury, TLR4 increases excitability in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, the brain structure that plays a major role in learning and memory.

Santhakumar explained two factors are involved in brain injury: a neurological complication and the immune system. These factors have traditionally been studied separately, she said.

“Our team, however, studied these factors together,” she added. “This approach helped us understand that the immune system operates through a very different mechanism in the injured brain than in the uninjured brain. Understanding the difference can guide us on how best to target treatments aimed at preventing epilepsy after traumatic brain injury.”

The team specifically studied concussions, the kind suffered by many football players, which can lead to cell death in the hippocampus, affecting the processing of memory. Cell death activates the immune system, including TLR4. TLR4, in turn, increases excitability in the hippocampus.

“What our rat studies on traumatic brain injury show is that if we target early changes in excitability, we can alter long-term pathology,” Santhakumar said. “Blocking TLR4 signaling shortly after brain injury reduces neuronal excitability in the hippocampus and seizure susceptibility. This seizure susceptibility is not reduced if we delay the blocking of TLR4 signaling after injury.”

Paradoxically, Santhakumar’s team found that drugs such as Resatorvid, which block TLR4 in the injured brain, caused epilepsy in uninjured brains.

“This paradox is difficult to understand,” Santhakumar said. “We are currently looking at molecular signaling pathways in injured and uninjured brains to make sense of it.”

The study could have important implications for war veterans returning home with brain injuries.

“Most often, the consequences of their injuries don’t show up a year later, but several years later,” said Santhakumar, who came to UCR in 2018 from Rutgers University.

The study focused only on epilepsy, one of several pathologies that can follow brain injury.

“Deficits in memory, cognition, and social behaviors could also follow brain injury,” Santhakumar said. “In future work, we plan to study co-morbidities associated with traumatic brain injury.”

Other researchers from UCR taking part in the study were D. Sekhar, D. Subramanian, and A. A. Korgaonkar, the first author of the paper. Joining from Rutgers New Jersey Medical School were Y. Li, J. Guevarra, B. Swietek, A. Pallottie, S. Sing, K. Kella, and S. Elkabes.

The research was supported by a grant to Santhakumar from the National Institutes of Health.