10 Years and Counting

Since its inception, the School of Medicine has worked to advance and increase access to healthcare in the region — and it’s just getting started

By Iqbal Pittalwala

I t is a truth universally acknowledged, that a fast-growing region lacking sufficient doctors, must be in want of a medical school. Inland Southern California, with about 40 primary care physicians for every 100,000 people — far fewer than the 60-80 recommended by the California Health Care Foundation — is such a region. In addition to general practitioners, the region is underserved in many medical specialties, too. It’s little wonder, therefore, that several decades ago UC Riverside, with demonstrated strength in the biomedical sciences, explored the idea of establishing its own medical school.

Today, UCR’s School of Medicine, which began with a staff of five people, is 10 years old — a significant milestone for the first public MD degree-granting medical school to open in California in the past four decades. To mark the anniversary, the school opened a new education building, allowing a gradual ramp up to a class size of 125 students per year and a total of 500 enrolled students in the four-year program.

In 2013, the school welcomed its inaugural class of just 50 students. For a spot in the most recently admitted Class of 2027, more than 6,000 students turned in applications. Only 86 made the cut, 73% of whom have ties to Inland Southern California and 44% of whom come from groups that are underrepresented in medicine. Many graduates of the medical school are the first in their families to complete a bachelor’s degree. Many also learned English as their second language.

The school’s mission to train a diverse physician workforce and deliver programs in clinical care and research is germane to Inland Southern California, an ethnically diverse region made up of Riverside, San Bernardino, and Imperial counties and home to more than 4.6 million people. Ranked fifth in the country for medical school diversity by U.S. News & World Report, the school is committed to improving the health of the region and addressing disparities among socially and economically disadvantaged populations. Through UCR Health, the school’s clinical arm established in 2016, the School of Medicine has extended its reach, delivering care to individuals and families in far corners of Inland Southern California.

Inception

UCR’s Division of Biomedical Sciences, launched in 1974, originated the idea of establishing a medical school on campus. The division also supported the UCR/UCLA Program in Biomedical Sciences, an accelerated Bachelor of Science/MD program, which preceded the School of Medicine. Neal Schiller, an emeritus professor of biomedical sciences who served as interim dean of the medical school in 2015, said the program was created to become a magnet for the strongest students in California and be an opportunity for UCR to distinguish itself. It took seven years to complete, with the last four years constituting the medical phase.

“This was a highly competitive program,” Schiller said. “Only 24 students were considered for the medical phase at the end of their third year. These students did two years of their medical education at UCR. The first year was basic medical science; the second year was clinical medical science. They completed their third and fourth years of clinical training at UCLA.”

The program almost ground to a halt in the mid-1980s when physicians at the San Bernardino County Medical Center, who trained the second-year UCR students, became unavailable due to a dispute between the medical center and UCLA.

“This jeopardized having the second year of the program at UCR,” Schiller said. “The second year required us to have a good number of physicians who could handle the clinical phase of the students’ basic medical training. Fortunately, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center stepped forward to handle the second year. But we wanted this second year back at UCR.” Eventually, the program found local physicians to train the second-year students, which gave UCR better control of the sequencing of the first and second years of the four-year medical phase of the program.

“Had we not brought back the second year, there would never have been an opportunity to start a medical school at UCR,” Schiller said. “We wouldn’t have had the experience of doing both the first and second years of training here.”

In 1997, the program was renamed the UCR/UCLA Thomas Haider Program in Biomedical Sciences after a generous gift to the program from Dr. Thomas Haider, a renowned spine surgeon, and his wife Salma. In 2008, the UC Regents approved UCR’s proposal for a medical school, making it the sixth in the UC system. In 2010, Dr. G. Richard Olds was named the founding dean. Two years later, the school received preliminary accreditation from the Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Full accreditation came in 2017, the year the School of Medicine graduated its first class of students.

Forging ahead

Since its inception, the School of Medicine has graduated more than 380 physicians, with 40% completing residency training in the region, said Dr. Deborah Deas, the Mark and Pam Rubin Dean of the School of Medicine and vice chancellor for health sciences, who joined the medical school in 2016. Additionally, more than 215 residents have been trained through sponsored graduate medical education programs in family medicine, internal medicine, cardiovascular medicine, psychiatry, and other specialties to help address the healthcare workforce shortage.

“What a change 10 years brings!” Deas said. “We are most grateful for the consistent support we have received from the community and the state legislature. Our journey over these years illustrates my favorite African proverb: ‘If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.’”

The medical school has succeeded in designing research programs that engage the community in work on health issues and disparities critical to Inland Southern California, such as the respiratory problems linked to toxic dust from the shrinking Salton Sea. The school’s pathway programs, which are older than the medical school, are another crowning achievement. They are helping diversify Inland Southern California’s healthcare workforce by supporting more than 1,200 local students annually in K-12 schools, community colleges, and universities in their path to medical school and health or science professions. One of the pathway programs, the Medical Scholars Program, received a national award this year.

“This program, which officially began in 2005, had 15 students in its pilot phase,” said Teresa Cofield, director of the pathway programs. “It quickly broadened resources for students, particularly community college students. It stands out among our pathway programs because it is a cohort-based multiyear program, allowing students to grow professionally over four years.”

A crucial goal of the medical school today is to expand UCR Health, which currently sees more than 45,000 patient visits annually. Plans are being made to increase clinic locations across Inland Southern California.

“We are providing patients with primary care and specialty care in areas such as neurology and behavioral health that are in short supply in our region,” said Timothy Collins, CEO of UCR Health. “The goal is to provide medical care closer to where patients are located. Our unhoused population needs different services and levels of care. We have opened a clinic in Riverside that focuses on serving this population. Our approach is to look at the holistic need for these individuals and make behavioral health and primary care available to them.”

Division undivided

The School of Medicine is home to several centers of research: The Center for Molecular and Translational Medicine (MolMed), which works on developing novel treatments in several medical fields; Bridging Regional Ecology, Aerosolized Toxins, & Health Effects (BREATHE) Center, which explores health effects of toxin exposures from the air; Center for Health Disparities Research (HDR@UCR), which addresses health disparities in Inland Southern California; Center for Glial-Neuronal Interactions (CGNI), which identifies risk factors and therapies for disease and dysfunction linked to the central nervous system; Center for Healthy Communities, which works on improving the health of diverse communities in Inland Southern California; Center for RNA Biology and Medicine, which focuses on research linked to ribonucleic acid present in all living cells and important for diagnosing human disease; and the Center for Cannabinoid Research, which studies the role in health and disease played by the cannabinoid system that controls many physiological functions in the mammalian body.

“Each center has a different origin and purpose and was initiated by people with a vision,” said Dr. David Lo, a distinguished professor of biomedical sciences and senior associate dean for research in the medical school, who leads BREATHE and HDR@UCR. “To have a research center at UCR like BREATHE makes good sense because Riverside is located at the edge of the Los Angeles basin, and we needed a center that focuses on the health impacts of air quality. HDR@UCR, which draws researchers on campus from sociology, psychology, anthropology, public policy, and engineering, has supported 25 projects or more that are community based.”

The Division of Biomedical Sciences is a pillar of strength for the school. The division’s nearly two dozen faculty members perform high-impact research on medically relevant topics and teach graduate students working towards their master’s or doctoral degrees. Craig Byus, who served as dean and program director of the UCR/UCLA Thomas Haider Program in Biomedical Sciences, worked with colleagues and community members to develop the program’s mission, focused on care for the medically underserved in Inland Southern California, which later formed the foundation of the mission for the School of Medicine.

“The school’s mission has been a guiding principle for how the division hires faculty and staff and how we develop,” said Monica Carson, chair of the Division of Biomedical Sciences, who launched CGNI, the division’s first center, in 2007. “We hold on to the mission and we are living it. Faculty interested in joining our division not only need to do top-tier science and research, but they’ve also got to be on board with the mission. It’s what draws a lot of researchers to us. They are here for research we can do as a community.”

Carson is pleased several of the division’s faculty hold leadership positions on campus and that the division is expanding its master’s program. She is pleased, too, with the vision the biomedical sciences faculty have developed: having sustainable research and an educational infrastructure that supports division cohorts at all career stages, with the goal of reaching the top quartile of their specific biomedical research fields. Carson has ensured the division continues to develop strategies to combat structural racism, prejudice, and inequities in research, teaching, and service. All the division’s faculty serve as dissertation mentors for graduate students and 95% of faculty members are funded by the National Institutes of Health, she said.

A pivotal moment in the division’s trajectory for Declan McCole, a professor of biomedical sciences who grew up in a rural, medically underserved community in northwest Ireland, was the establishment in 2016 of MolMed, a center led by fellow biomedical professor Maurizio Pellecchia.

“It was clear he had great leadership potential that manifested itself in this center,” said McCole, who joined UCR in 2013 and was one of the first research faculty members hired to help start the medical school. “It also provided a spark for other members of the division who had ideas of establishing centers. MolMed was a big moment for us and helped make the division’s footprint bigger. It also built on the success of other campuswide centers such as CGNI, where biomedical sciences faculty are heavily involved. Moving forward, I see opportunities for the division to expand its capacity to do translational research and have high hopes for UCR to get its own hospital, which would dramatically increase our translational and clinical research capabilities.”

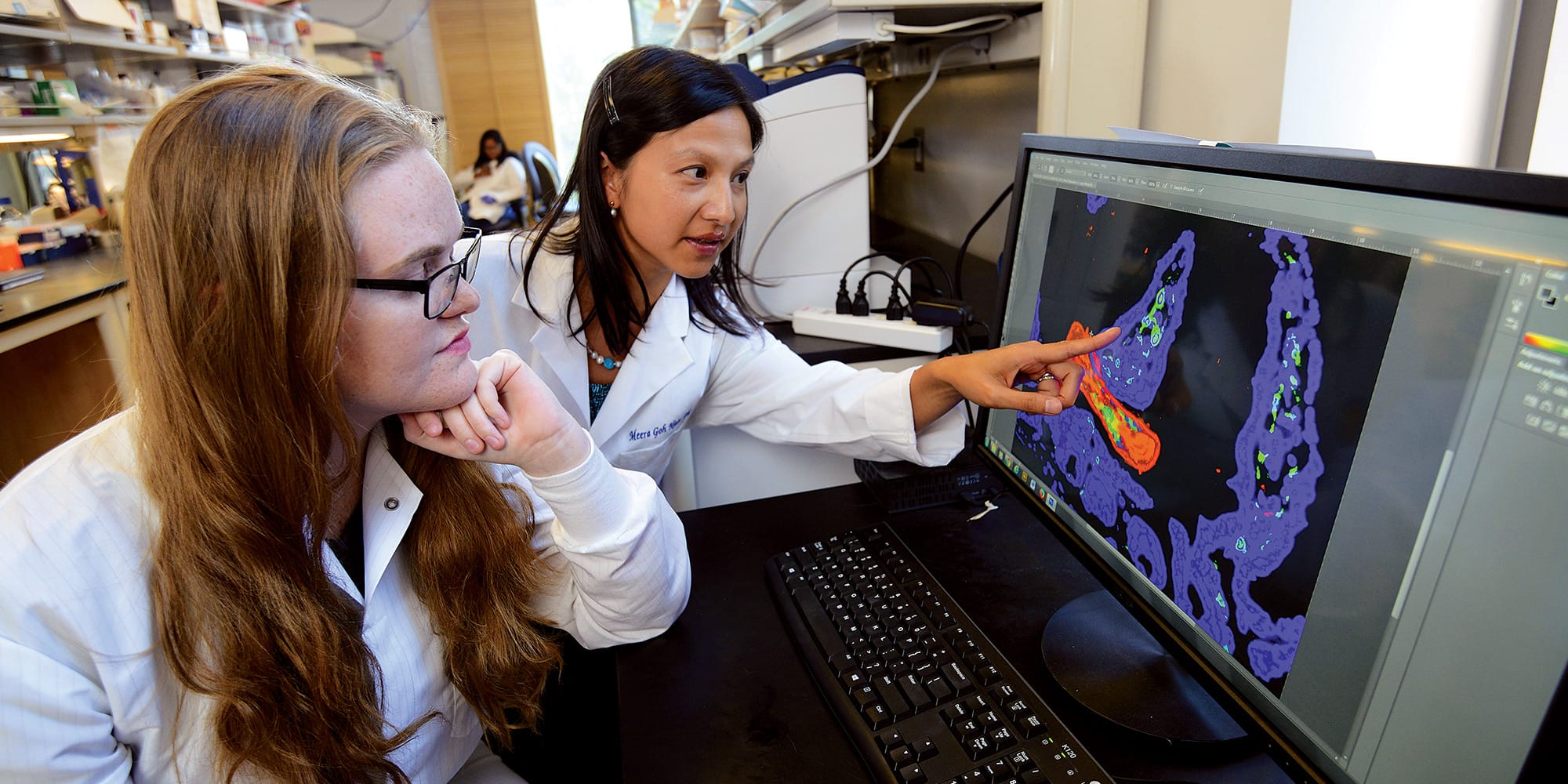

For Meera Nair, who joined UCR the day the medical school got its preliminary accreditation in 2012, MolMed has been a cornerstone in the Division of Biomedical Sciences’ success in placing UCR on the map in terms of innovative research on drug development. She believes the enhanced community engagement with HDR@UCR has also been transformative.

“Having an ongoing dialogue with community stakeholders in our region that shapes our research questions has been enlightening and motivates my research endeavors,” said Nair, an associate professor of biomedical sciences. “Moving forward, I’d like to see us focusing on expanding translational and clinical research to address health problems in our community.”

Nair remembers interviewing the medical school’s first cohort of students. She was overjoyed when one of the students recently got in touch with her.

“Dr. Jonathan Pham, who joined and graduated from our medical school, is now a practicing physician in our area,” she said. “He reached out to volunteer to give his first lecture to our medical students. We’ve come full circle.”

Emma Wilson, a professor of biomedical sciences who joined the division in 2008, would like to see the school increase research in infectious disease and immunology. There is also growth potential at the division for cancer research, she said.

“I see growth areas in doing more translational research and collaboration with our community-based physicians and researchers that would provide unique training opportunities for our graduate students and be mission focused in design,” Wilson said.

Mission in action

The school’s 10-year anniversary has had a particular impact on its alumni, including Dr. Antonio Garcia, now an associate physician at Kaiser Meridian Clinic in Riverside.

“Riverside is my home, so after completing medical school, I went into residency at the UCR School of Medicine,” said Garcia, who received his MD in 2020. “I specialized in family medicine because I wanted to take care of everyone — from newborns to older adults. At my clinic, I take care of patients of all ages. I also want to help teach the next generation of doctors.”

To achieve this goal, Garcia signed up to be part of the medical school’s signature program, the Longitudinal Ambulatory Care Experience, which helps medical students serve local patients while building their foundation as physicians. Garcia is excited to work with a UCR medical student in January 2024. He is delighted, too, to see the medical school’s hard work pay off.

“Thanks to this medical school, we are improving and increasing access to healthcare,” he said.

“Being a new physician, I’ve had the pleasure of seeing patients who have not seen a doctor in many years due to access issues. With the medical school continuing to grow, we will be able to provide excellent healthcare to all our community residents. Physicians like me and others are proof that the school’s mission statement and goals are being realized. We are staying in the area, we are working with our community, and we are teaching the next generation of physicians. I’m so proud of all the school has accomplished in the past 10 years. I can’t wait to see what it accomplishes in the next decade.”

HISTORY OF THE SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

1974

UCR’s Division of Biomedical Sciences is launched; the UCR/UCLA Program in Biomedical Sciences is formed.

1997

The biomedical sciences program is renamed the UCR/UCLA Thomas Haider Program in Biomedical Sciences after a generous gift to the program from Dr. Thomas Haider and his wife.

2003

Then-Chancellor France A. Córdova appoints a panel of academics and education leaders to begin planning for a four-year medical school.

2008

The UC Board of Regents approves the establishment of the School of Medicine.

2009

Dr. G. Richard Olds is named founding dean of the School of Medicine and vice chancellor of health affairs.

2011

The School of Medicine Research Building opens and serves as a model for sustainable laboratory design.

2012

The School of Medicine Education Building is opened; the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) grants the School of Medicine preliminary accreditation, making it the sixth medical school in the UC system and the first public M.D.-granting medical school to open in California in more than 40 years.

2013

The first class of 50 students is welcomed to the School of Medicine for the traditional white coat ceremony.

2016

Dr. Deborah Deas is appointed the Mark and Pam Rubin Dean of the School of Medicine and CEO for clinical affairs.

2017

The LCME gives the School of Medicine full accreditation; the inaugural graduating class of 40 students receives MD degrees and recites the Hippocratic Oath.

2019

State legislators approve $108 million in the state budget for construction of the new School of Medicine Education Building II (SOM Ed II).

2021

The UC Board of Regents gives final approval for SOM Ed II and the School of Medicine hosts a groundbreaking ceremony to kick off its construction.

2023

The School of Medicine celebrates its 10th anniversary and officially opens SOM Ed II.

SOM SPOTLIGHTS

Michelle Burroughs

director of community engagement and outreach, Center for Healthy Communities

“Working in the medical school’s Center for Healthy Communities is profoundly meaningful as it empowers me to champion health equity and create positive change in diverse, underserved communities.”

Bio: Burroughs addresses health disparities through community engagement in research and health initiatives. With more than 25 years in public health, she excels in program administration and collaboration with diverse organizations, and has received recognition for her contributions to diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Current Research: The Center for Healthy Communities’ Black Health Equity Initiative (BHEI) is committed to addressing health disparities in Black communities. By fostering trust, addressing systemic racism, and improving healthcare access, BHEI empowers Black community members to take control of their health. Burroughs’ work focuses on helping community members develop self-efficacy skills to enhance well-being and promote health equity, an important endeavor in pursuing equitable healthcare and improved community health outcomes.

Teaching at SOM: “As a preceptor, I teach effective community engagement to students, nurturing their passion for meaningful involvement. I aim to impart skills for impactful community interactions and inspire a lifelong commitment to community well-being.”

Martín García-Castro

professor, biomedical sciences

“Working at the School of Medicine allows me to lead original developmental and stem cell biology research while contributing to increased access and opportunities for our underserved community.”

Bio: Before joining the School of Medicine in 2014, García-Castro was an associate professor at Yale University and a postdoctoral fellow at Caltech. His work on the origin and differentiation of neural crest cells (NCCs), which are key contributors to craniofacial and peripheral nervous system development and are involved in multiple pathologies, has pioneered studies in animal and human models, advancing basic and translational efforts.

Current Research: García-Castro’s lab uses state-of-the-art strategies combining classic chick embryology with a powerful pluripotent stem cell model to understand when, where, and how NCCs are formed. Simultaneously, his lab assesses how NCCs contribute to pathologies, including rare syndromes like Mowat-Wilson and deadly cancers like melanoma. The lab also pursues regenerative medicine gains, for example, through cornea generation.

Teaching at SOM: “I teach early developmental biology, promoting critical thinking, thirst for knowledge, and, whenever possible, I advocate for social justice. At the medical school, I cherish like-minded collaborative colleagues engaged in improving teaching, research, and community.”

Kimberley Lakes

professor, clinical psychiatry and neuroscience

“The opportunity to contribute to the development of something new and innovative inspires and challenges me. The medical school’s mission to reduce health disparities aligns closely with my values and my desire to make my work meaningful.”

Bio: Lakes joined the School of Medicine in 2018 and engages in research, teaching, and clinical practice. Her numerous awards include a Fulbright Global Scholar award, Aspen Brain Forum Prize in Neuro-Education, Young Investigator Award, National Institutes of Health awards for Health Disparities Research, and a Visiting Scholar Fellowship from the University of Oxford.

Patient Care: Lakes specializes in neuropsychology and mental health at UCR Health, the clinical arm of the school.

Current Research: Lakes’ research spans the fields of clinical child neuropsychology and developmental cognitive neuroscience. She is interested in holistic, innovative, and culturally relevant interventions to promote self-regulation — the ability to manage emotions and impulses — in children and adolescents. Current grant-funded studies include the development of digital health interventions to improve and support self-regulation by promoting healthy behaviors and by delivering evidence-based psychological intervention.

Teaching at SOM: “I teach neurodevelopment and therapeutic interventions to psychiatry residents and medical students and hope to foster a deep understanding of contextual influences on patients’ lives and therapeutic skills that are applicable across clinical contexts.”

Scott Pegan

professor, biomedical sciences

“I share the medical school’s vision of a California where the full spectrum of our population, ranging from those of meager backgrounds to those that serve our nation and everywhere in between, should have access to quality healthcare.”

Bio: Pegan joined the School of Medicine in 2021. His research focuses on the discovery of antivirals through immune system regulation and antidotes for nerve and pesticide agent poisoning. Beyond being a lieutenant colonel serving the U.S. Military Academy at West Point as a science and technology adviser, Pegan has partnered with industry and federal agencies on research for drug discoveries and holds several U.S. and international patents.

Current Research: Pegan is working on therapies and vaccines for Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic Fever. Caused by one of the World Health Organization’s priority pathogens, there are no treatments for this often-fatal disease. U.S. service members succumbing to this disease and its spread to new countries have raised alarms. In the same spirit of assisting service members, Pegan also helps develop new antidotes against nerve agent poisoning.

Teaching at SOM: “Serving others and the wonders of science have been lifelong draws for this native Californian, which is encompassed in the spirit and mission of the School of Medicine.”

Natalie Zlebnik

assistant professor, biomedical sciences

“The School of Medicine is meaningful to me because it is deeply rooted in the community and seeks to improve the lives of residents of Inland Southern California.”

Bio: Zlebnik joined the School of Medicine in 2021. She came to UCR after completing a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, where she focused on the role of the endocannabinoid system in normal reward-motivated behaviors and its therapeutic role in disorders of reward seeking, such as eating disorders. She examines how drugs that are misused or abused exploit neural mechanisms of motivated behavior to promote relapse and facilitate the transition to drug addiction.

Current Research: Zlebnik seeks to understand how the reward circuit of the brain is altered by chronic drug intake to drive relapse long after drug exposure has ended. This allows her lab to develop interventions that restore normal circuit function to improve recovery and abstinence. Researchers in her lab can probe the mouse brain in ways they cannot in humans, but treatments they have identified can still provide significant benefit for humans.

Teaching at SOM: “I am personally invested in this medical school because it comprises individuals who truly believe in its values and mission.”

Changcheng Zhou

professor, biomedical sciences

“At the medical school, I have the opportunity to teach and train the next generation of researchers and physicians and improve the health of our local communities.”

Bio: Zhou joined the School of Medicine in 2019. His research focuses on understanding the molecular mechanisms of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. He is a fellow of the American Heart Association and the recipient of the Cardiovascular Toxicology Impact Award from the Society of Toxicology. Earlier this year, he received a grant of nearly $6.8 million from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to study the link between environmental chemicals and cardiovascular disease.

Current Research: Zhou’s lab is investigating how exposure to certain chemicals, including common chemicals found in consumer products such as plastics, increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. In addition to changes in diet and lifestyle, the chemical environment to which we are exposed has significantly changed in the past few decades. Zhou’s lab is trying to understand how exposure to these chemicals contributes to the development of several chronic human diseases.

Teaching at SOM: “I teach cardiovascular physiology and liver metabolism. I hope our medical and graduate students gain fundamental knowledge from my courses and develop clinical and research interests in several high-prevalence diseases, such as heart and liver diseases, that affect the Inland Southern California population.”

Bringing Health Home

By School of Medicine staff

Timothy J. Collins began his appointment as the new chief executive officer of UCR Health, the clinical enterprise of the School of Medicine, in May 2023. His appointment is the latest chapter in a career spanning over 30 years in acute care hospitals, health systems, and academic medical centers. Collins’ core belief is what underpins his dedication to serve the community and improve healthcare in Inland Southern California. “It’s not about me or the success that I might have. It’s about what I can do for others,” said Collins, who holds a doctorate in education from Creighton University and master’s and bachelor’s degrees from the University of Southern California.

His path through the world of healthcare is rooted in his experiences as a lifeguard in Laguna Beach, when he found himself wondering what happened to the people he rescued. That curiosity laid the foundation for a lifelong medical career, which started with emotionally and physically challenging work as an emergency medical technician and grew into an array of positions dedicated to improving community health. Among them, running hospitals, serving as a healthcare consultant for international companies, volunteering with the San Diego Sheriff’s Department Search and Rescue team, and even leading an earthquake response team in Nepal. Having grown up in the region, Collins’ connection to Southern California helps fuel his latest endeavor leading UCR Health. His family is here, and he feels a strong obligation to address healthcare disparities in the area.

“The School of Medicine is meaningful to me because it is deeply rooted in the community and seeks to improve the lives of residents of Inland Southern California.”

As part of the UC system, UCR Health has a mission to provide quality care and service to patients across Inland Southern California, Collins said. UCR Health currently sees over 45,000 patient visits annually and has expanded access to specialties, including pediatrics, neurology, and minimally invasive gynecology. Collins intends to build on this progress by increasing services and capacity, especially in underserved urban and rural areas. He remains committed to enhancing clinical quality and fostering collaboration with local clinics, hospitals, and community-based organizations to strengthen overall care for the community. As he looks to the future, Collins said he was impressed with the passion and capability of UCR Health staff and physicians.

“I hope that people will be excited about UCR Health’s presence and its commitment to invest in providing healthcare services to those in need,” he said.

❯ Learn more about UCR Health at ucrhealth.org.