A new avocado variety that’s more than a half-century in the making will soon be available to growers in the world marketplace.

It’s called the Luna UCR™ and offers consumers great flavor, a rind that turns a tell-tale black when ripe, and high postharvest quality. Growers, meanwhile, will benefit from a smaller tree size, allowing denser plantings for more efficient and safer harvesting, and minimal pruning.

It also has a type of flower that makes it an efficient pollinizer for various avocado varieties, including the stalwart Hass, the world’s leading variety. Planting the Luna UCR™ intermingled with other varieties could help ensure good yields by increasing pollination rates.

Developed by University of California, Riverside, agricultural scientists, the Luna UCR™ is officially known as the BL516. It is protected under a pending patent that credits Mary Lu Arpaia, a UC Cooperative Extension horticulturist based at UCR, and her colleague Eric Focht, a UCR staff research associate in the Botany and Plant Sciences Department in the College of Natural and Agricultural Sciences. Other credited “co-inventors” are former UCR scientists Gray Martin, the late David Stottlemyer, and the late B.O. “Bob” Bergh, who left UCR in 1991.

The variety will be marketed to growers worldwide through a partnership with Eurosemillas, SA, a company based in Spain that specializes in international marketing of proprietary crop varieties. Under an agreement worked out by UCR’s Office of Technology Partnerships, Eurosemillas is the licensee of the variety. Eurosemillas has established partnerships with growers in 14 countries outside of the USA to grow the Luna UCR™.

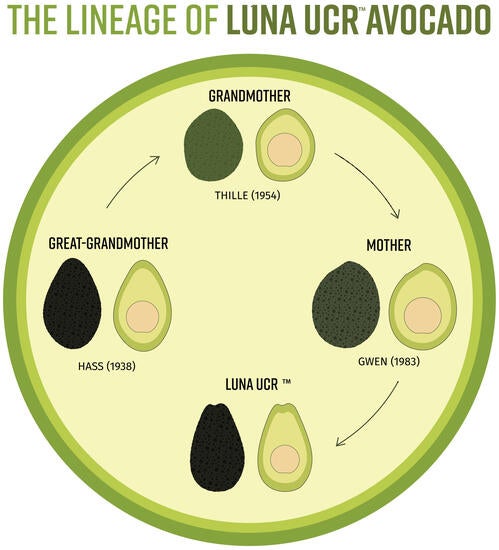

The development of Luna UCR™ has been intergenerational. It goes back to the work of Bergh in the 1950s, explained Arpaia, who described him as UCR’s “first real long-term avocado breeder.”

Back then, the avocado industry sought a green skinned Hass as an alternative to the smooth-skinned and green-colored Fuerte avocado – the nation’s top seller from the 1920s to the 1970s. Meaning “strong” in Spanish, the Fuerte is so named because it survived deep freezes in Los Angeles in the early 20th Century. It has excellent flavor but was a problem for growers because it’s an alternate fruit bearer, which meant the trees produce robust fruit crops only once every two years.

The Hass, meanwhile, had much going for it, including a great nutty flavor and a skin that easily peeled. But, in the mid 1950s or so, consumers turned their noses to the Hass, because they associated its black skin when ripe with rotten, spoiled fruit, explained Focht.

So, Bergh went to work, planting thousands of genetically different avocado seedlings from a Thille avocado, an offspring of the Hass, in search of a perfect green version of an otherwise Hass-like fruit. So, more than 20 years later, in 1983, he succeeded with the release of the Gwen, named after his wife.

Unfortunately, the Gwen avocado was a commercial flop – because the black-skinned Hass had made it after all.

Technology and advertising solved consumer issues with the black skin. The use of ethylene gas in warehouses allowed for the uniform ripening of avocados that are picked when they are still green. And a “Ripe for Tonight” advertising campaign taught consumers that avocados are ripe and ready to eat when the skin turns black.

The arrival of drip irrigation meant Hass groves could be planted on steep hillsides, including those along the Interstate 15 corridor on both sides of the border between Riverside and San Diego counties. This allowed for a great expansion of the industry in Southern California in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Because of its green skin, the Gwen was left behind before it was introduced, even though it has wonderful properties, including its flavor, its ability to bear fruit every year, and a smaller tree size for easier harvesting with less pruning.

Bergh was taken aback, but not defeated, Arpaia said. He recognized that although Gwen had not found a place in the commercial marketplace, it might provide the basis of future avocado varieties.

“So, he decides in 1985 he's going to make one big final push because he's getting older and getting ready to retire,” Arpaia said. “Knowing what I know about Bob, he never gave up.”

Bergh planted as many as 70,000 genetically different seedlings from Gwen mother trees at three sites with different climates in San Bernardino, Ventura, and San Luis Obispo counties. Hedging his bet paid off when all the trees planted in the Mentone area of San Bernardino County died in an unusually deep freeze. Yet, one of the Ventura Country trees that grew in Camarillo became the first of what is now the Luna UCR™ avocado, with the preferred black skin when ripe. Unfortunately, Bergh will not see the release of this fruit of his labor. He died in 2021 at age 96.

“Fruit breeding is a very long-term process,” Arpaia said. “So, you build upon the shoulders of your predecessors.”

What’s next for UCR’s avocado breeders?

“We are looking to collect and plants seeds again next year,” Focht said.

“So, 20 years from now, I’ll be on a patent. I’ll be 90 years old, but still on the patent,” Arpaia said.

Click here for a video version of this story