THE BAERS AND THE BEES

UCR’s Barbara Baer-Imhoof and Boris Baer founded the Center for Integrative Bee Research to safeguard bees and secure human food production

By Jules Bernstein | Photos by Stan Lim

M eet the Baers, the sweet married couple who work together, play together, and are quietly saving the world together. They’re helping honey bees survive, which in turn ensures us humans get to keep eating for the foreseeable future. The continuous collapse of honey bee colonies, caused by culprits including parasites, pesticides, and environmental changes, is plaguing beekeepers worldwide, threatening global food security. The Baers are at the forefront of the fight against this problem.

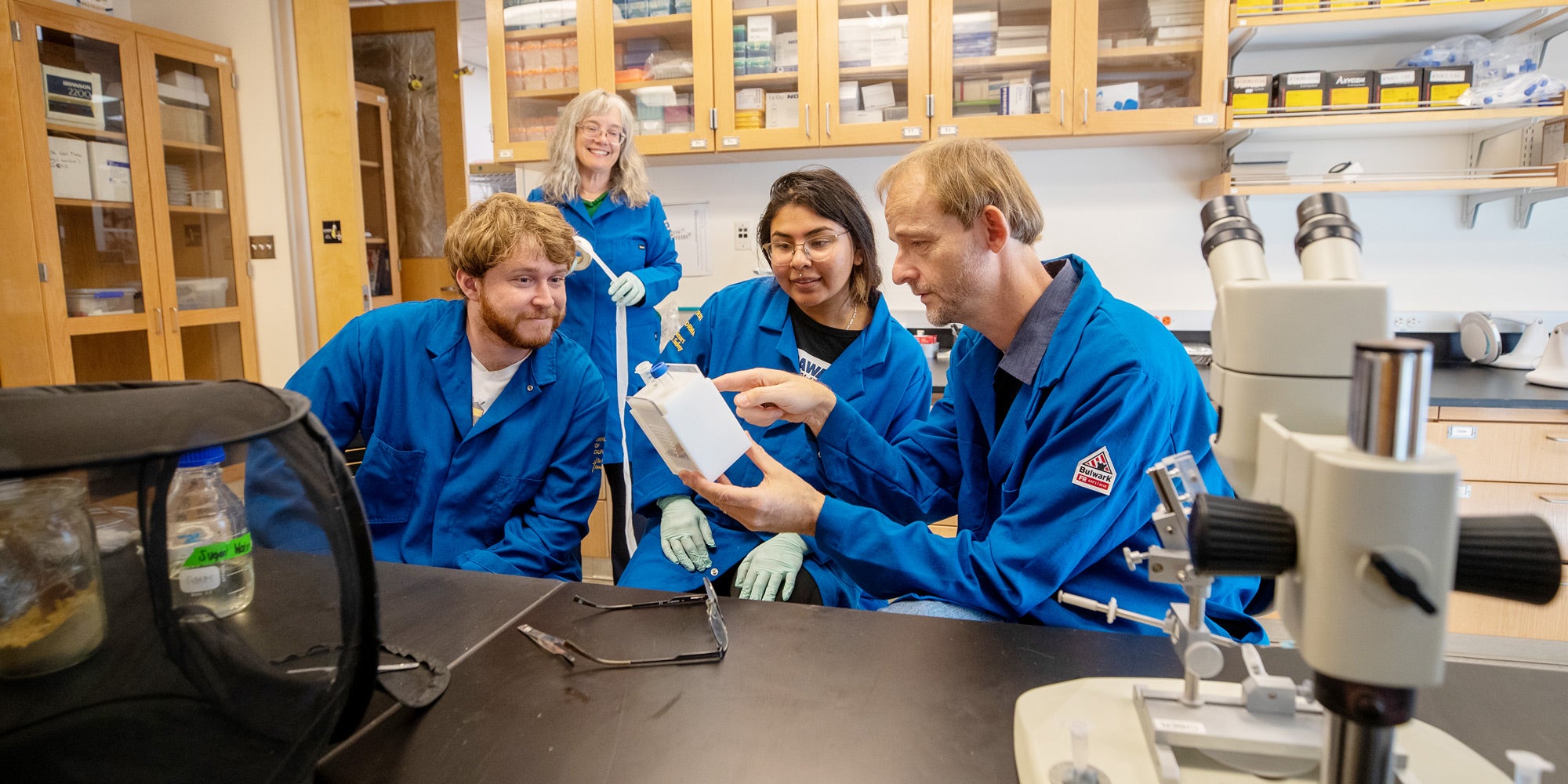

Barbara Baer-Imhoof and Boris Baer founded the world-renowned Center for Integrative Bee Research, or CIBER, to serve as a beekeeping think tank. The center, now based at UC Riverside, is one of the largest honey bee health networks in the country, enabling entomologists, engineers, economists, and professional beekeepers to collaborate on innovative solutions for colony collapse.

Perhaps it is surprising then, given the gravity of their work, the first sound you’d have heard from the hallway on approaching the center’s most recent weekly staff meeting is raucous laughter. On arrival, Barbara offers newcomers muffins and freshly brewed cappuccinos. She asks whether to include sugar. Early meeting topics include the nature of the perfect laboratory pet and attendance at an upcoming pizza party. The atmosphere is festive, yet serious lab business is eventually settled.

“We definitely push a friendly environment here, because we believe people do their best if they’re happy to come to work,” said Boris, a UCR professor of entomology. “Everyone’s best is certainly needed to solve the daunting challenges facing the bees.”

Bees pollinate more than 80 crops, with a global estimated annual value of $220 billion. Over the past year, U.S. beekeepers reported losing roughly 45% of their hives, with similar losses reported worldwide. These losses have been happening on this scale for nearly 20 years — the magnitude of the problem is not small.

“Every third bite of food you eat has been pollinated by a bee,” said Barbara, a research specialist at UCR. “The issue is even more serious than fewer foods for the buffet table, or even some financial setbacks.”

Boris added, “Bees save human lives. The crops they pollinate provide vitamins and other chemical compounds we need to be healthy. Without bees we will lose people to health issues. It’s more than nutrition; it’s human wellbeing that’s at stake.”

MEANT TO BEE

Barbara was not always certain she wanted to study bees, but she knew from a young age that she wanted to dedicate her life to a big humanitarian cause.

“I had this ambition as a kid,” Barbara said. “I wanted to save the world.”

It was this ambition, matched with Boris’ enthusiasm for bees, that ultimately resulted in CIBER. Their match was made 26 years ago in Switzerland, the Baers’ home country. Barbara was a third-year doctoral student in biology at ETH Zurich, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, when she was asked to serve as a mentor to Boris, a first-year doctoral student. She found his enthusiasm for bumblebee research infectious, he made her laugh, and the connection was instant.

“We’re not high school sweethearts, but Ph.D. sweethearts,” she said. Boris recounts their early years with deadpan comedic delivery.

“Barbara was basically my supervisor at that time. I was the rookie,” he said. “She showed me how to catch bees and rear them, which isn’t easy. And because bumblebees are reared in climate-controlled rooms under red light, I always joke that I met my wife in the red-light district, which is actually true.”

Living and working together isn’t for everyone, but Boris says the circumstances of their early years helped set the foundation for the successful partnership they share today. Bumblebee breeding can be challenging and the workload on graduate students brutal, so lab partners must learn to be truly supportive. The Baers worked day and night in graduate school, up to 80 hours a week.

“I learned how much I can trust her in those years,” Boris said. “If she told me she was going to do something, I came into the lab the next morning and it was always done.”

Having a shared goal also helped them in navigating past smaller disagreements.

“You have to stick your heads together on problems to solve them. I think that really helped us then and still does,” he said. “We can passionately fight with each other about science, so we don’t have to fight about anything else.”

For a time following her doctorate, Barbara was unsure she wanted to continue working as a scientist. She went on to get an MBA, worked in banking, then became a full-time mom to the couples’ two children. She supported Boris as his academic career took them from Zurich to Copenhagen, Denmark; then to Perth, Australia. When she eventually returned to science, Barbara knew exactly why she’d come back. The bank work didn’t excite her in quite the same way that solving existential problems did. With that renewed sense of purpose, and Boris’ ever-present enthusiasm, the Baers moved CIBER from Perth to its current home at UC Riverside.

CIBER SECURITY

The Baers see CIBER as a platform to encourage collaboration amongst scientists from four other UC campuses as well as commercial beekeepers. Of all the threats to commercial beekeeping that CIBER participants must solve, arguably the most serious is the varroa mite. These mites mainly attack honey bee larvae and pupae, latching on to them and eating their fat bodies. The fat loss weakens the bees, and the mites transmit viruses and bacteria while eating.

As humans began to travel around with managed honey bees, this mite jumped from Asian to European-managed bees, whose immune systems were not prepared for it. The mites then spread around the world, reaching the U.S. in the 1980s. This year, after several unsuccessful tries, the mite established itself in honey bee colonies on one of the last formerly unaffected continents, Australia.

“We don’t have any real treatments, it is difficult to suppress, and it has become semi-tolerant to the treatments we do have,” Boris said. “If you ask beekeepers what they’re most worried about, it’s the mites.”

Another more recently established honey bee pest is the small hive beetle, whose larvae burrow and tunnel through combs, consuming broods, pollen, and honey. They also produce a repellent slime, so bees have a hard time removing them from their hives. Honey ferments in the damaged combs, and colonies collapse within weeks.

One way CIBER scientists are addressing these pests is through breeding and artificial insemination. There is a honey bee found only in Southern California that appears tolerant of mites as well as the region’s extreme heat and drought. Genetically, they are the most diverse bees in the world, and unlike the Africanized bees that form part of their ancestry, some of these bees are manageable, not defensive.

Dubbed “survivor bees” for their ability to withstand environmental stresses, they carry mite loads up to five times smaller than other bees. It’s not clear whether the survivors repel the mites, or the managed bees are more attractive mite targets. Breeding survivors with other bee populations holds promise for creating managed hives that thrive.

“California was always a spoiled state. We had gold, then struck oil, and now we have these bees,” Boris said. “If we can crack into their natural resistance, it could have major impact.”

The CIBER team is identifying and isolating volatile substances produced by survivor bee larvae, which keep nearby mites away and warn worker bees about them. Identifying the survivor bee colonies capable of producing the most of these helpful chemicals, and using those colonies in a breeding program, will help mitigate the danger posed by the mites.

The team is also doing a similar thing with survivor bees’ resistance to other infectious agents. They’ve isolated four different substances that kill an intestinal parasite called Nosema, which is a particular problem for hives used in almond pollination. Nosema gives the bees diarrhea and prevents them from keeping their hives clean

“With the chemicals we’ve already identified from survivor bees, up to 70% of infected hives are completely cured of Nosema,” Boris said.

There are other factors impacting the bees, including pesticides, that have a synergistic effect. If a hive is healthy, it can withstand a lot of stress, even pesticides to a certain degree. However, if the hive is struggling with parasites, they’ll be hit much harder by heat waves or insecticides.

“When it comes to bees, one plus one can equal three,” Barbara said. “One stressor magnifies the effects of the others.”

To keep additional bee stresses at bay, she is spearheading an effort to develop a scent that will repel bees from flowering plants treated with deadly pesticides. Scientists from UC Berkeley, the California Research Alliance, German chemical company BASF, and UCR’s Department of Molecular, Cell and Systems Biology have been working through CIBER for the past two years to find these scents. The group identifies compounds that are promising repellant candidates, then Barbara tests them in both the lab and the field, “to see if the bees wrinkle their noses at the chemicals.”

Finally, the group is looking to give beekeepers tools to better monitor the health of their hives. Tiny devices designed in conjunction with UCR mechanical engineers will be able to “listen” and “smell” inside hives for distress signals. The goal is not only to record health data, but to use artificial intelligence and machine learning to develop algorithms that can detect the earliest possible onset and causes of problems and warn beekeepers while there’s still time to act. Preventative devices like these are key because once the colony collapses, it’s too late to bring it back.

“We know bees have a special pheromone they give off when they’re hungry or dying, and these can be traced,” Boris said. “We are essentially building electronic veterinarians.”

Their analyses of bee behaviors and genetics are also yielding surprising results. For example, males possess seminal fluid toxins that temporarily blind queens during mating. The goal, apparently, is for a single male to ensure its genes get passed on by making it more difficult for a queen to mate with others.

While some of their results have been a surprise, the Baers’ overall success is not. They intentionally foster an environment that attracts others who are passionate about their common goal. Honey bees cannot thrive in solitude, and neither, in their opinion, can human beings. “You can’t keep a single bee in a cage, it will die,” Barbara said.

“There are so many problems and so much negativity around us,” Boris added. “There’s a virus, inflation, a war, possible recession. People have had enough. We try to find ways to turn those frustrations into positive energy that helps us find solutions. We have an environment at this university that makes our work possible, and we never take that for granted.”

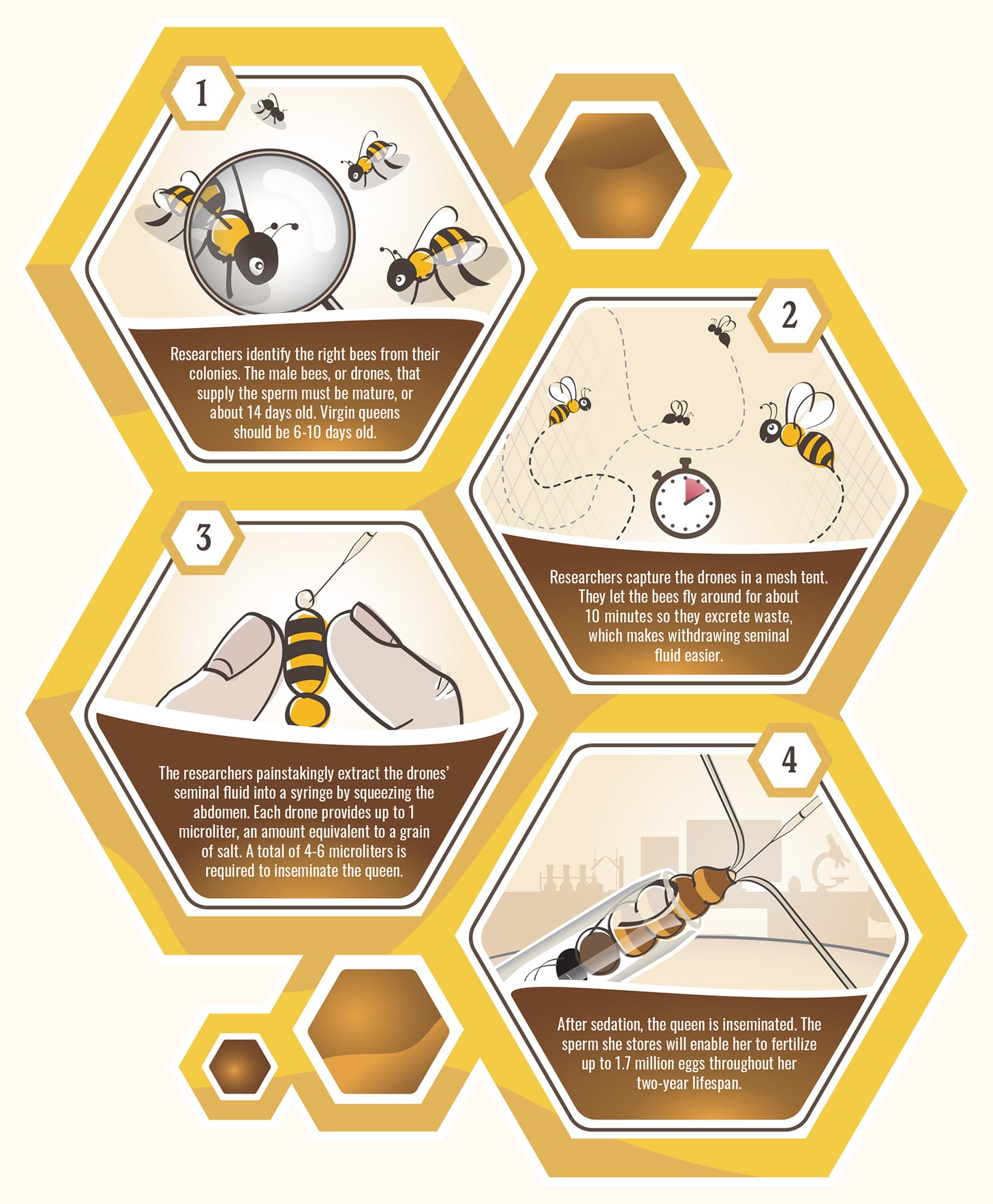

BREEDING BETTER BEES

By John Warren | Illustration by Rick Donato

Boris Baer and Barbara Baer-Imhoof are at the forefront of an innovation that involves artificially inseminating queen bees with male sperm in a laboratory setting. It leads one to wonder why bees would need help propagating. How long has the phrase “the birds and the bees” been drilled into us, after all? There are several reasons.

Researchers at CIBER are working to create a strain of honey bees that can withstand the Southern California heat. They also want to create bees that are resistant to the Varroa mite and more than 80 other parasites. Finally, they are on a quest to create less aggressive bees, diluting the highly defensive strains that began infiltrating the Southwest U.S. a generation ago. Let’s take a look at this process:

We need your help to safeguard the future for bees.

Philanthropic donations support UCR’s important research, beekeeping, and outreach activities. If you would like to contribute, please contact robyn.martinelli@ucr.edu or dubron.rabb@ucr.edu in the Office of Development or visit ciber.ucr.edu.

Return to UCR Magazine: Fall 2022