R STAR

Brighter Futures, Cleaner Skies

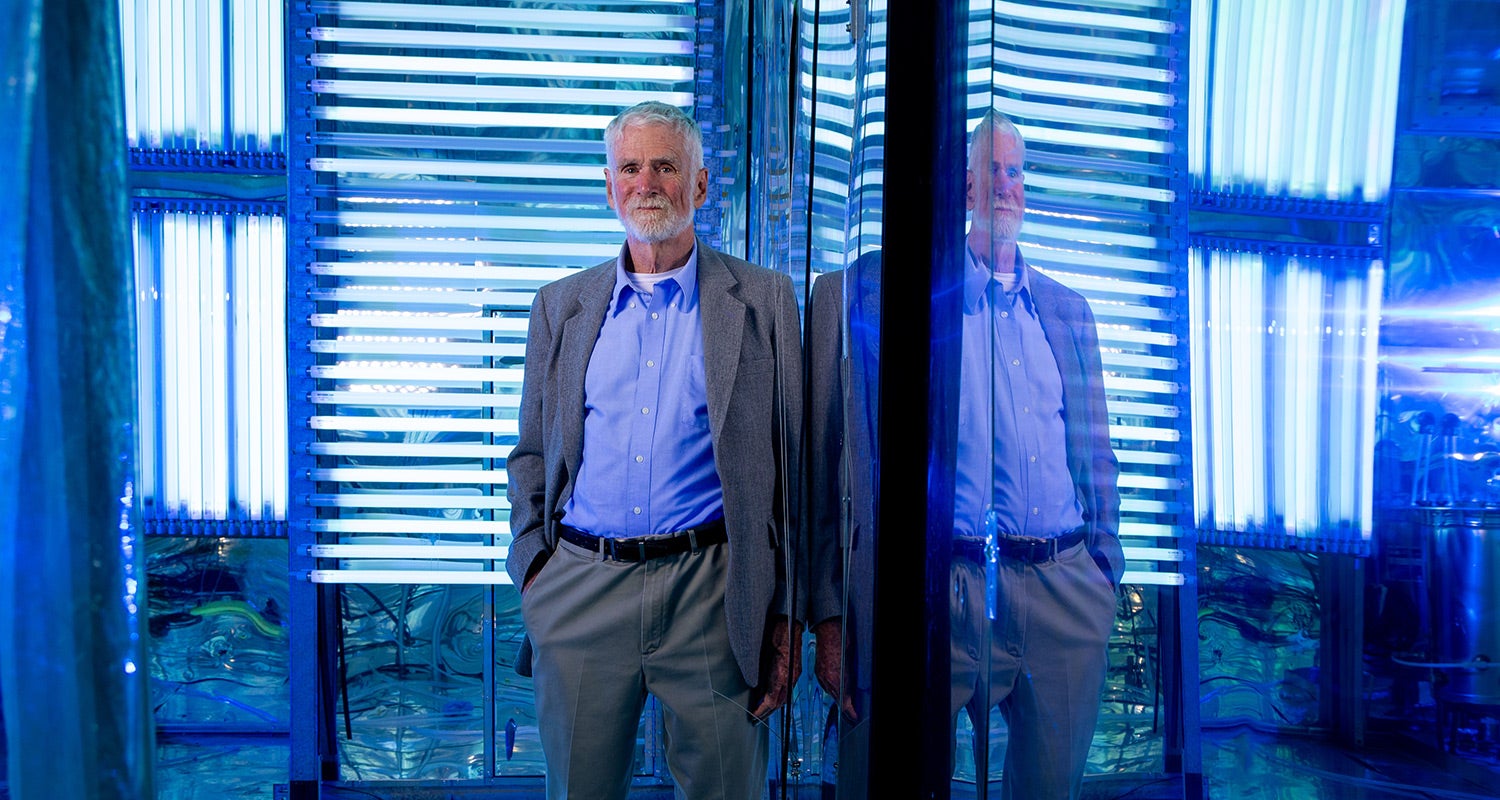

UCR alumnus and longtime faculty researcher William Carter has made two gifts to support students and advance environmental research

F or more than 50 years, William Carter ’67 has helped shape how we understand and regulate the air we breathe. Through his work at the intersection of experimental chemistry and computer simulations, the models he develops — known as chemical mechanisms — are key to our understanding of air pollution and developing effective strategies to improve it.

Although Carter retired from his full-time position as a research chemist in 2005, he has continued his work as an emeritus faculty member. Here, Carter shares more about his career journey, his research, and his two recent gifts to UCR that will champion both environmental research and student success.

You first came to UCR in 1963 as an undergraduate? Why did you choose to study here and how was your experience?

When I was graduating from high school in Seattle, I applied to various universities and one of them was UC Berkeley. They were essentially full at Berkeley, but they offered me a place at UC Riverside, which I hadn’t heard of before. I found UCR was preferable to Berkeley because the campus was fairly small and had a nice feel. I chose to major in chemistry because I had fallen in love with the subject in high school. At UCR, one of my professors recognized me as one of the better students and offered me the opportunity to do undergraduate research in gas phase kinetics. I even learned glass blowing to make the vacuum systems used in my experiments. That research paved the way for my career in atmospheric chemistry.

After graduating from UCR, you earned a doctorate from the University of Iowa. Why did you return to Riverside?

I remembered research being done in the emerging field of air pollution by Professor James Pitts at UCR’s Statewide Air Pollution Research Center (SAPRC). It wasn’t exactly what I’d been doing as a graduate student, but it was related, and the work sounded interesting to me. I knew Professor Pitts because the only “B” I ever got in chemistry was from him — it was in analytical chemistry, which was my weakness. So, I reached out and joined the center as a postdoctoral researcher, and I’ve been at UCR ever since. I eventually moved my research to the Center for Environmental Research and Technology (CE-CERT) where I led the design of the indoor atmospheric chamber, the world’s largest facility to study chemical processes in the atmosphere.

Tell us about your research in atmospheric processes. What is a chemical mechanism and how does it help curb air pollution?

A chemical mechanism predicts how the primary pollutants — the pollutants that are emitted — react to form secondary pollutants, and then how the secondary pollutants react. Chemical mechanisms represent very complex processes because a single compound released into the air can result in thousands of reactions and hundreds of new products. When I joined SAPRC in 1973, there weren’t really any good chemical mechanisms for air pollution models. My first job was developing mechanisms for the formation of ozone from hydrocarbons in car exhaust, solvent evaporation, and other sources, which I updated and improved several times over my career. These mechanisms are part of the intelligence in air-quality models used by regulatory agencies to guide policies and by companies to develop cleaner products and better control strategies. The policies have led to dramatic improvements in air quality.

You recently pledged to UCR $2.2 million to support environmental research and $1.45 million to support undergraduate students. Tell us about these gifts.

The first gift establishes the Atmospheric Chemical Mechanism Research Endowed Fund at UCR. I hope it will enable someone to build on the work I’ve done. There aren’t many young scientists focused on mechanism development, so this could help support a graduate student or postdoc with an interest in that area.

The other gift honors my late friend and fellow alumnus Michael McCall and it supports students in UCR’s Highlander Early Start Academy (HESA). I wanted to support motivated students with a financial need, but not necessarily high-achieving students who would have no difficulty getting scholarships from other sources. The gift supports HESA students in their second through fourth years, after they have established that they are motivated to succeed. The first cohort of six students will be receiving their scholarships this academic year — I’m excited to follow their progress.

Read more about Carter’s research in a related article at news.ucr.edu/carter-gift.