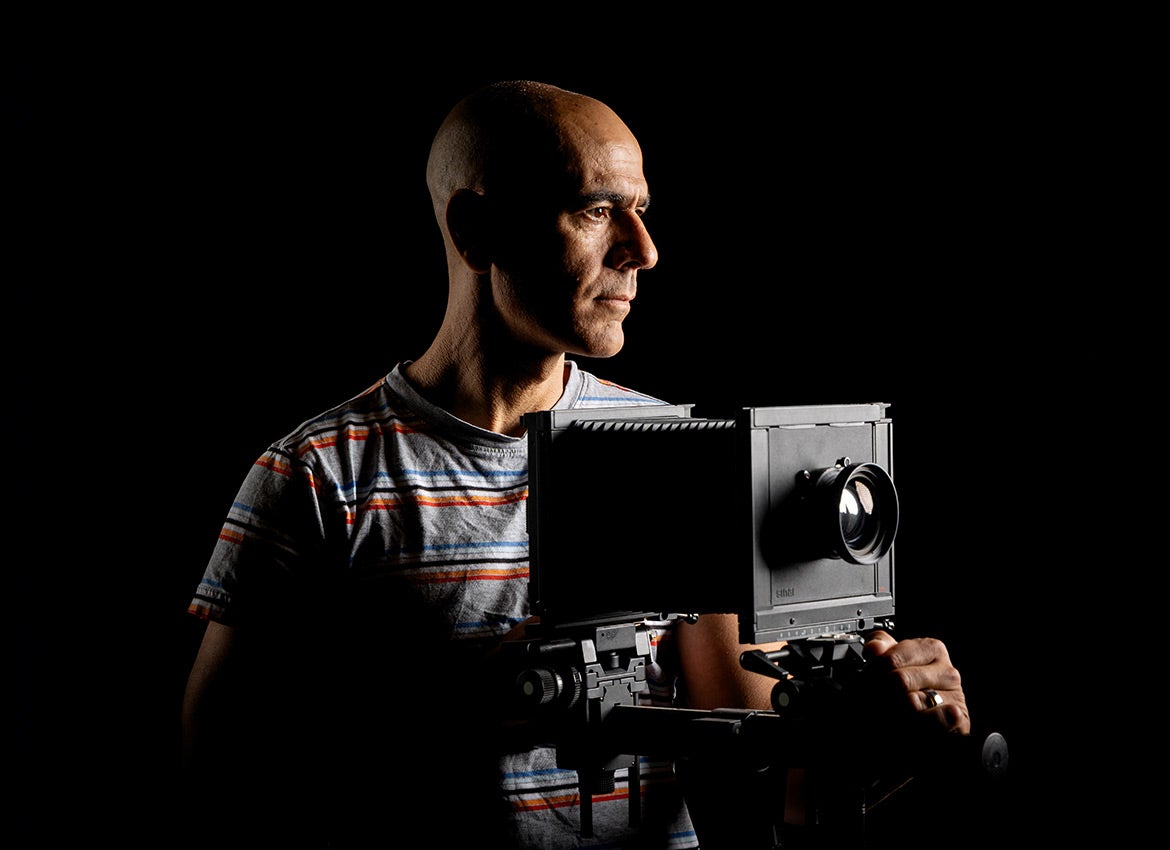

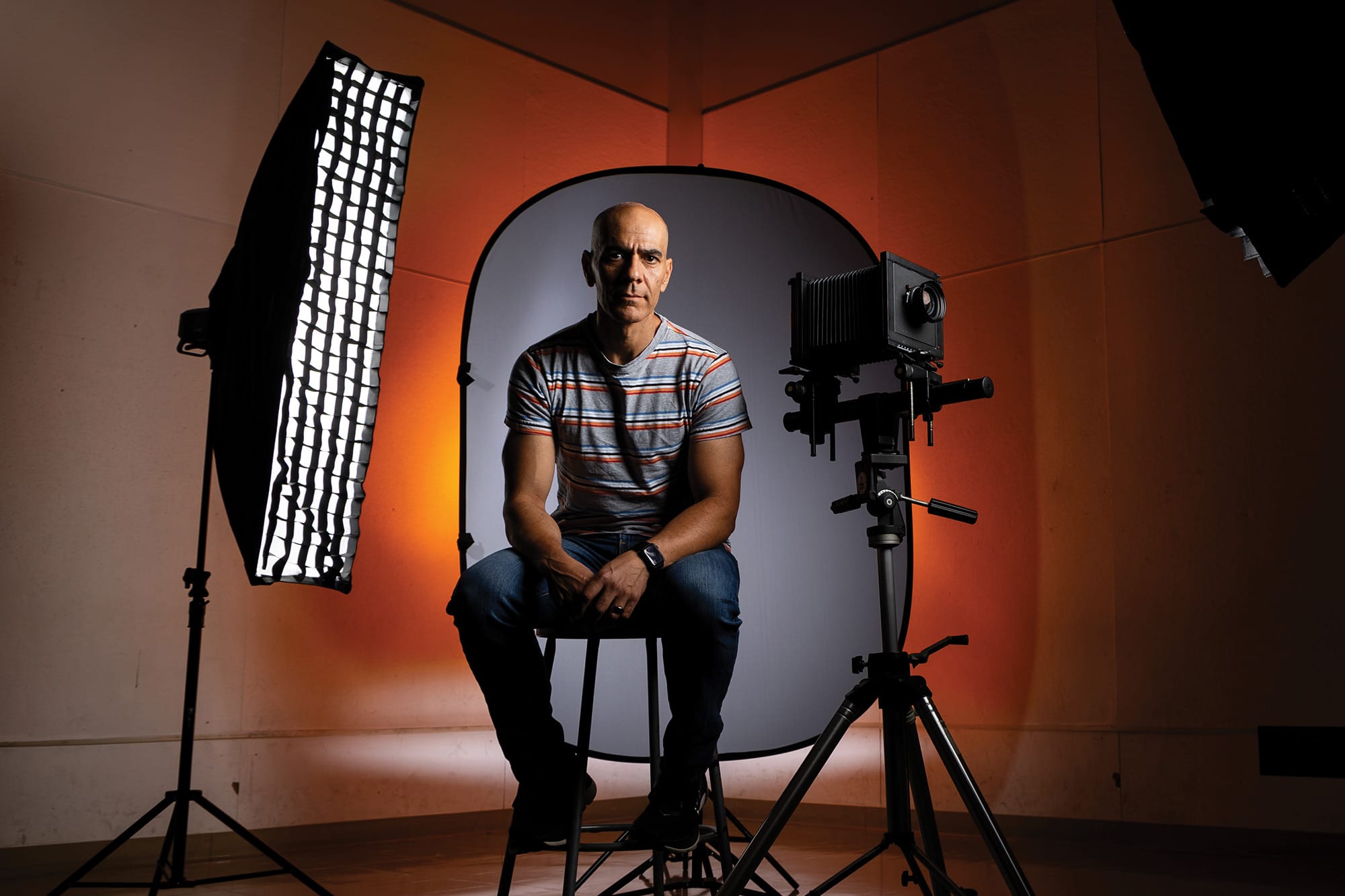

The BIGGER picture

Photographer Amir Zaki shares how an inoperable brain tumor brought what matters most in life into focus

By Nicole Feldman | Photos by Stan Lim

A mir Zaki has a much better reason than most to be afraid.

On September 2, 2023, the UC Riverside professor of art woke up in the middle of the night seizing on his right side before passing out. After a few days in the hospital, he found out he had a brain tumor that could not be removed without leaving him partially paralyzed.

Two years, a biopsy, dozens more seizures, unrelenting nerve pain, and many life changes later, Zaki is still not sure what his future will look like. Yet while he has plenty of reasons to tremble from the uncertainty, in some ways, his stress level has actually gone down.

Why? Priorities.

“I wanted to spend as much time as I possibly could doing things I enjoy,” Zaki said.

It all started with what he thought was a tennis injury three years earlier. In September 2020, Zaki started feeling numbness and tingling in his right leg that developed into nonstop nerve pain.

“I went to everyone,” he said. “I went to neurologists, I went to back specialists, I had multiple MRIs. None of it made any difference.”

Then came the grand mal seizure in September 2023 that sent him to the hospital, where doctors finally discovered he had a rare, slow-growing brain tumor called an oligodendroglioma; a biopsy confirmed it was inoperable. Sitting on the region of the brain that controls the sensory part of his right side and some motor function, it explained the nerve pain — but didn’t solve it. If anything, the pain got worse after diagnosis, and he started having minor seizures every few days.

“My emotions were up and down,” Zaki said. “When I came home, I was walking with a walker. My motor and sensory control of my right leg was very, very depleted because of all the convulsions.”

Doctors hoped the 28 days of radiation and year of chemotherapy that followed would stop the seizures. They didn’t. And, while medication has helped reduce the frequency, Zaki continues to have minor seizures about once a month and lives with chronic pain in his leg.

“It ranges from having a fly buzzing around your face 24 hours a day to having a bee constantly stinging you,” he said of the ongoing pain. “It’s maddening.”

Zaki’s long-term prognosis also remains uncertain. His condition has remained relatively stable thus far, but he continues to have routine MRIs to monitor the tumor and look for any changes.

“It’s just a full-on existential crisis,” he said. “Not knowing is, of course, the worst. Everybody will tell you that when you’re waiting for the results of something. Now my life is a perpetual version of that.”

Life Through a New Lens

Long before his tumor diagnosis, Zaki found success as an artist with his photographic work exploring the intertwining of the built and natural landscapes of his home state of California. Born in Beaumont, he earned a bachelor’s degree in art from UCR in 1996, followed by a master’s from UCLA. He later returned to instruct art at UCR, where he has been teaching since 2000. Over his 25-plus-year career, his photography has been exhibited in numerous shows nationally and internationally and can be found in the permanent collection of the Getty Museum.

Following his hospital stay, Zaki went on medical leave from UCR for two quarters. And while he has since returned to teaching and art making, his life has profoundly changed.

“I have a very different life now,” he said. “I don’t do things in the evening. I don’t do things that are stressful. I don’t drink or smoke or do anything ‘fun’ like that. I have this regimented life because it gives me some control.”

Although he wishes he could wake up tomorrow pain-free, not all the changes have been bad.

“I think a lot of people have invisible difficulties and challenges that we don’t talk about,” he said.

“I am now one of them. Having more compassion toward others, understanding that everybody is dealing with something, has been really eye-opening.”

In some ways, the tumor has caused him to discard parts of who he was before, allowing the things that bring him the most joy to rise.

“I had a kind of epiphany, and my priorities became crystal clear,” Zaki said.

Before discovering the tumor, he would spend time on Twitter (now known as X) arguing with people about things like identity and social politics.

“I completely dropped all of that,” he said. “The things that became important were my family and decreasing my daily stress levels.”

“Having more compassion toward others — understanding that everybody is dealing with something — has been really eye-opening.”

A surprising shift has been his relationship with podcasts. Formerly a podcast junkie, Zaki has not only lost interest but is now repulsed by them.

“It just became clear that I didn’t want to keep filling my time and my ears with the kinds of things that I knew I was going to hear,” he said. “I see so much fear, and it’s all because people are listening to podcasts, or watching the news. Do you know how afraid I could be? But I’m not because it doesn’t serve me.”

He still enjoys having philosophical conversations, but these days he opts to have them in person, where he can have a “nuanced, calm conversation,” instead of on X or listening to them on a podcast.

“There’s so much real-life common ground,” he said. “The things that fall outside of that get so much airplay, but I’m much more attracted to human connection.”

A Change in Tune

Now, instead of listening to podcasts on his hour-long commute from Huntington Beach to Riverside, Zaki opts for music. He has also reprioritized making his own.

“Those formative years of like 15 to 20, I played with my friends until late at night,” he said. “We drank beer and played our own music, and I learned to play drums on my own. Music has been something I’ve always been interested in but never really figured out a way to make it a big part of my life.”

In the summer of 2024, Zaki put out a listing on Craigslist and formed a new band along with his daughter, who serves as the band’s lead vocalist. Now, the time he once devoted to Twitter is used to jam with his daughter and other bandmates. Along with the joy it brings, making music also provides a welcome distraction from his chronic pain.

“Playing live with other people is the closest thing I can think of to real magic,” he said. “There is nothing else I’ve experienced in my life that demonstrates how powerful it feels when you connect, physically, with a group of other people. It’s spiritual.”

Zaki also now offers drum lessons to beginners. He hopes to eventually start a children’s music school where instead of just teaching kids to play, they learn to create music of their own.

“We’d get someone who wanted to play guitar and someone who wanted to play drums and bass and sing, and we’d put them all together,” he said. “That’s a fantasy of mine.”

At UCR, Zaki has also found a renewed sense of joy in teaching photography, largely by removing stress from the classroom.

“For a long time, my philosophy was that my job as a teacher of art was to turn my students into artists,” he said. “That has changed, and it has taken a big weight off.”

The reality is that most of his students, despite their major, do not intend to pursue art as a career. Where once he felt it his duty to mold them into art professionals, he now simply focuses on helping them to improve, without post-graduation expectations looming.

“I love the students at UCR who are really engaged in what they’re doing,” he said. “It’s like they’re a little fire. The trick about teaching is to recognize and help stoke that fire.”

Relaxing and taking the stress out of it has made him a better teacher, he said. He jokes more, gets to know the students one-on-one.

“My mood in the room teaching has completely changed,” he said. “I’m much more myself, and it’s very rare to feel like I don’t ‘have them.’”

Of course, none of this removes the nerve pain he still feels every day. It doesn’t cut down the never-ending doctor’s appointments or ongoing seizures.

“If I could choose to have a cure tomorrow — if I could choose not to have gone through this — I would,” he said.

But he can’t. So instead of letting fears about his condition or the future or what people are saying on X consume his life, he focuses on mindfulness, diet and exercise, his family, and doing things that bring him joy.

“I recognize that I am still privileged,” he said. “I live in a safe place. I have a good job. I really see the finite amount of time that I have. I try my best not to be a victim, to control the things I can, and stay above the petty stuff.”