The Messy Nature of Things

An environmental historian and curator for the Huntington Library, Daniel Lewis finds meaning in the tangled nexus of human understanding and the natural world

By Jessica Weber | Photos by Stan Lim

A gas station in a remote region north of the Arctic Circle may seem an unlikely place for an epiphany, but it’s where Daniel Lewis marks a defining moment that sparked a lifelong passion for birding, and by extension, the history and science of the natural world.

Sitting in his office on the sprawling grounds of the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California, where he has been a curator for nearly 30 years, Lewis recalls the fateful road trip from his time as a UCR doctoral student. During summer break, he and his former martial arts instructor embarked on a month-long odyssey through Canadian and Alaskan backcountry to “go for a swim” in the Arctic Ocean. Perusing the racks of a rusty carousel of paperbacks while stopped for gas, Lewis happened upon the second edition of National Geographic’s “Field Guide to the Birds of North America.”

“I opened it up and suddenly the world came crashing in,” he said.

“I thought, ‘oh my gosh. I can make sense of the world.’ It can be classified. It can be organized. So, I’ve had this sort of obsession with field guides for a long time because of the things they tell us about humans’ attempts to understand the tumbling, messy nature of evolution in the natural world.”

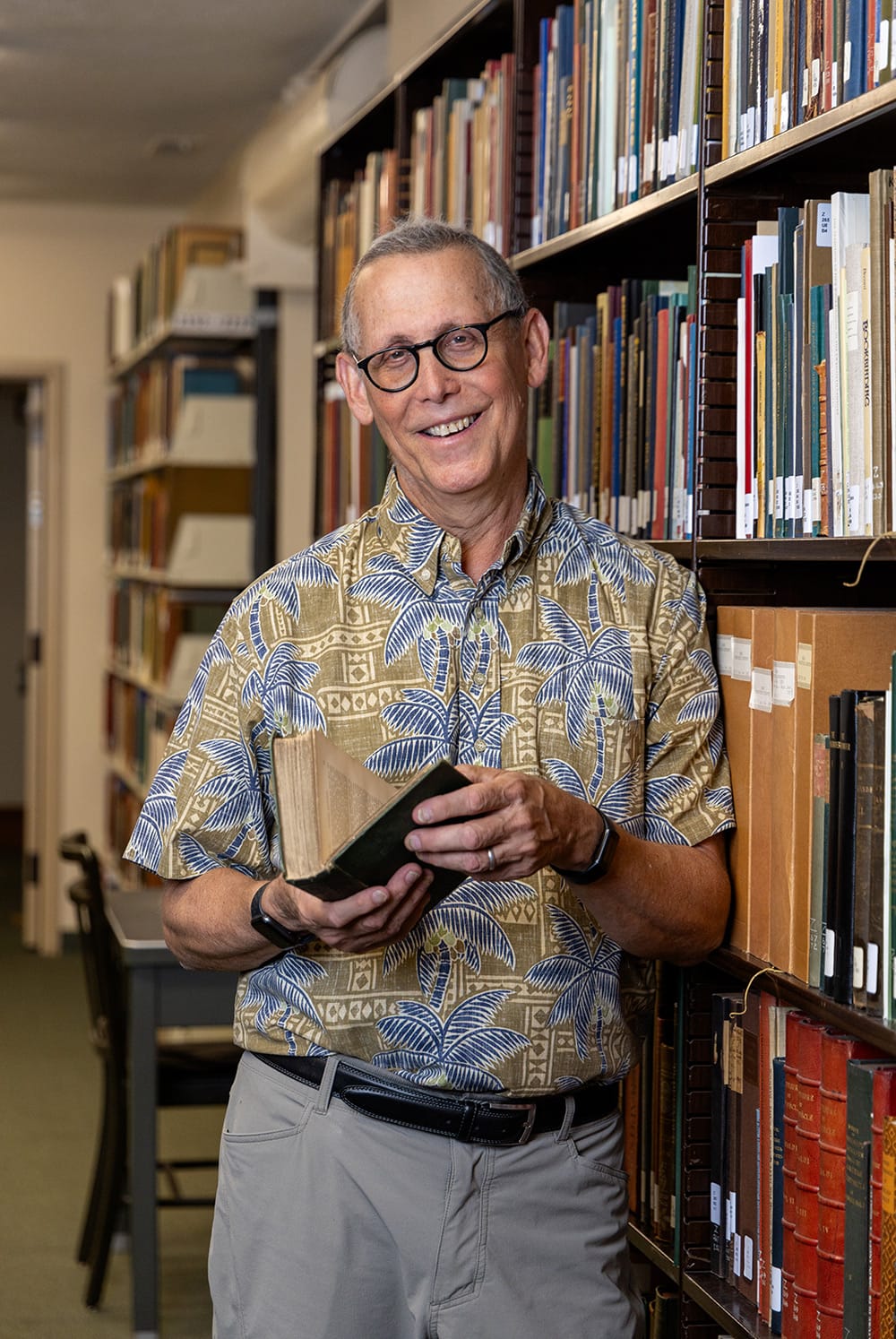

As the Dibner Senior Curator for the History of Science and Technology, Lewis manages the Huntington’s collection of science holdings from 1800 to the present. An award-winning author and environmental historian, he has written several books exploring topics in the natural sciences — including two about birds — and holds a faculty appointment at Caltech, where he teaches a range of environmental history courses. He has been featured in local, national, and international media outlets as well as a PBS documentary series, and has even won an Emmy. And while his career has been far ranging and prolific, Lewis describes the road that led him here as “wobbly.”

Growing up surrounded by the lush beauty of Hawaii, Lewis says he’s always had a deep appreciation for nature, but decided to pursue writing in college, moving to California after high school and earning a bachelor’s degree from the University of Redlands in English and creative writing. He worked in the special collections division of Redlands’ A.K. Smiley Public Library after graduating, fostering an interest in rare books and manuscripts, and went on to earn a master’s in historic resource management and archival studies at UCR in 1988, followed by a doctorate in Latin American history in 1997.

Lewis came to know the Huntington and its curators while serving as the company historian for The Los Angeles Times in the mid-90s, and later from conducting his own research using materials from the Huntington’s collections for his doctoral dissertation on railroads in Mexico, the result of which later became his first book, “Iron Horse Imperialism.” It was during this time, in 1997, that a curator at the Huntington encouraged him to apply for a temporary position filling in for another curator. Halfway through what was meant to be a 21-month stint, the Huntington’s then-history of science curator left for a role at the Smithsonian Libraries, and despite having little to no familiarity with many of the subjects in the collections he was to oversee, Lewis was offered the role.

“As he likes to say, ‘I left so that Dan could have a job,’” he said of the previous curator’s departure. “They took a leap of faith because I’m not trained as a historian of science, but then I was exposed in the best possible way to all the immense holdings in the field. It’s really been a case of learning on the job.”

At Home at the Huntington

Along with 16 themed gardens covering 130 of the 207-acre grounds and an extensive collection of European and American art, the Huntington is home to a world-renowned research library with around 12 million items dating from the 11th to 21st centuries.

Within these vast holdings, Lewis oversees hundreds of collections spanning both the physical and natural sciences from the 19th century on, covering topics like physics, astronomy, engineering, botany, ornithology — “all of the ologies”— totaling around half a million books, manuscripts, prints, and other ephemera. Out of necessity and already possessing an innate but untapped love of natural sciences, Lewis was quick to adapt, becoming an expert in a range of scientific topics through managing the collection and working with the scholars researching them, noting the immense privilege of having access to some of the most groundbreaking works in human history at his fingertips.

“These books have passed through many hands over the long decades of their lives,” Lewis said. “And so the lives of people are inscribed in these books — their drops of sweat, the things they leave in the margins. There are all sorts of bits of forensic evidence about how the book has been used and by who.”

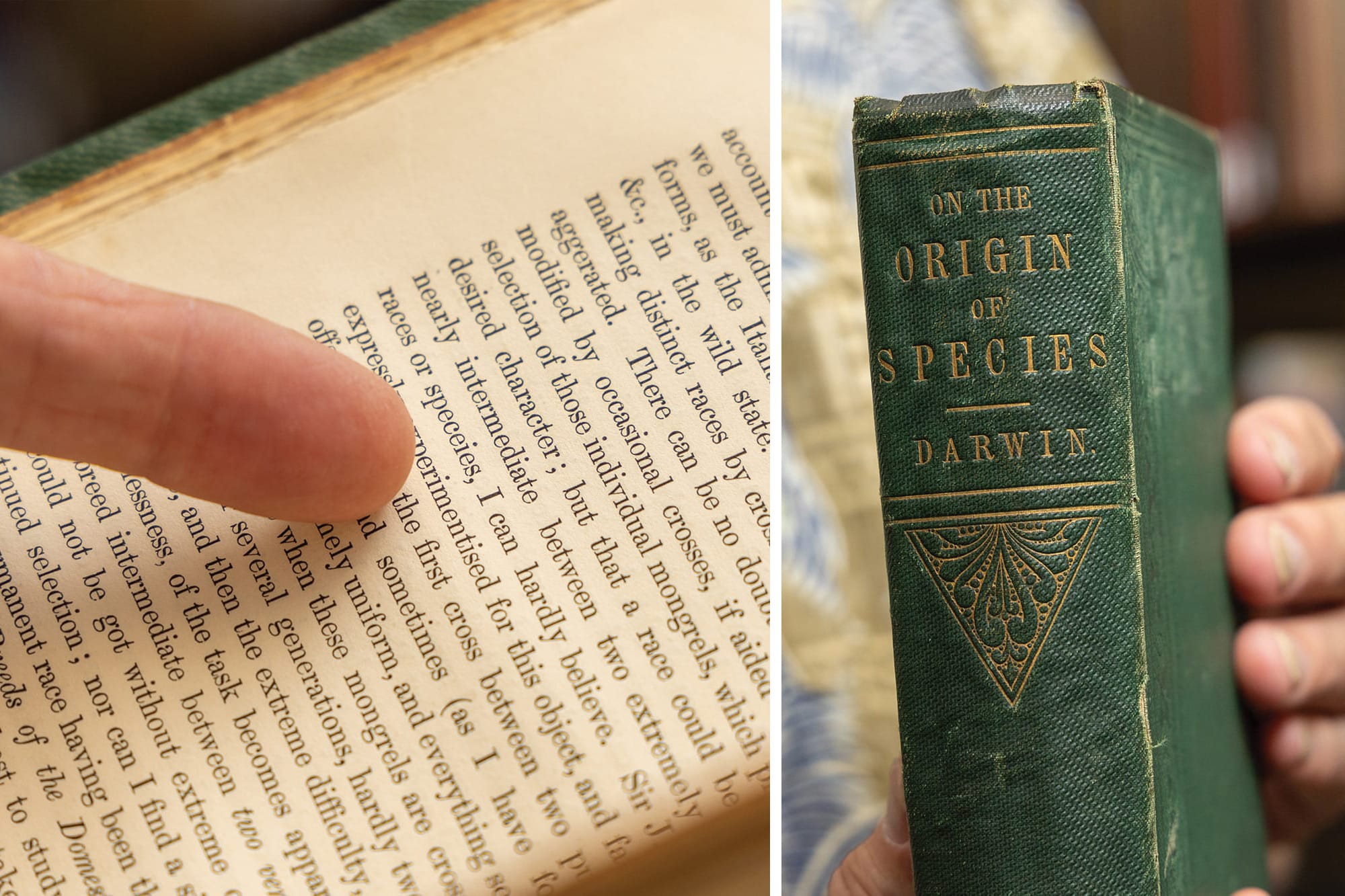

Of the many rare and precious materials in the collections, Lewis’ favorite is the first edition of Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species.” Published in 1859, Lewis said Darwin’s seminal work on adaptation and natural selection has been profoundly influential to him both personally and professionally, calling it “one of the most important books in the history of science ever written.”

“Research isn’t history and scholarship isn’t alive unless somebody with a pulse is doing it.”

Of the 1,250 first editions printed, he has been able to track down around 450 surviving copies, noting many were burned or otherwise destroyed due to the controversial nature of the content at the time. And while early editions of Darwin’s work look very similar, all with the same green cloth binding, he says there is a telltale sign to look out for to know if it’s a coveted first edition.

“Turn to page 20 and count down to line 11 — they’ve misspelled the word ‘species,’” he said, noting genuine copies can be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. “So, if you are ever at a yard sale and you see one of these, call me.”

The Huntington is currently the only library in North America with four first edition copies of Darwin’s book, two of which arrived in 2006 with the acquisition of the Burndy Library collections, a vast undertaking overseen by Lewis. Consisting of 47,000 rare books, 20,000 reference books, and about 2,000 linear feet of archival collections, it was a career milestone, marking the single biggest acquisition since Henry Huntington’s initial gift establishing the Huntington, and allowed for the endowment of Lewis’ position.

“The things that I’ve acquired for the Huntington over the last 29 years have a huge impact on the trajectory of research,” he said. “Ideally, people 50, 100, 200 years from now will still be making use of these materials. Research isn’t history and scholarship isn’t alive unless somebody with a pulse is doing it.”

Along with stewardship of the science and technology collections and managing acquisitions, Lewis works with researchers who come to utilize collection materials and regularly gives talks to donors, docents, and other groups on science topics. He has also curated a number of exhibitions for the Huntington, a skill he says he learned “by the seat of the pants,” having no prior experience.

In 2008, Lewis was charged with curating an exhibition that stemmed from the Burndy Library acquisition called “Beautiful Science: Ideas that Changed the World.” The exhibition was presented in four parts, covering astronomy, natural history, medicine, and light/optics — a nod to electrical engineer and Burndy Library founder Bern Dibner that included a display of 400 historic lightbulbs.

“Most people’s favorite thing about the exhibition were these light bulbs,” he said. “It was a great exercise in humility, and showmanship, and craftsmanship, and just how to engage the public. They really were beautiful, though.”

The year after it opened, “Beautiful Science” was named the “best exhibition in America” by the American Alliance of Museums and was visited by roughly 3 million people during its run. Lewis is now working on the next iteration of the exhibition, a larger, multimillion-dollar project set to open in 2029 following completion of a major renovation to the building housing the Huntington Library.

Speaking for the Trees

Despite the unexpected turn toward the sciences, Lewis never abandoned his passion for writing. Instead, his work stewarding the Huntington’s vast collections and the access it has afforded has nurtured a symbiotic career writing books about topics in the natural sciences and his love of the natural world. Following the publication of his book on railroads, Lewis published “The Feathery Tribe” in 2012, a book about the professionalization of ornithology at the end of the 19th century and how the study of birds was influenced by Darwin’s theories of evolution. His 2018 book “Belonging on an Island” examines the extinction, evolution, and survival of birds in his home state of Hawaii and what it means to be a native species.

“The natural world is messy, and at the same time, we’ve tried so valiantly to organize it,” he said. “Something about that combination of organizational tidiness and messiness is very interesting to me.”

Lewis’ most recent book “Twelve Trees,” published in March 2024, combines memoir with a globe-spanning perspective on the vital importance of trees to an increasingly inhospitable planet. From the towering redwoods along the coast of California, to Africa’s resilient baobabs, to the “Lost Tree of Easter Island” existing only in a handful of botanical collections around the world, Lewis tells the storied history of a particular species in each of the book’s 12 chapters, exploring connections with his own life and the inextricable roots between all of humanity.

“What I really wanted to show is why these trees matter both collectively and individually,” he said. “It is really a story about climate change and hope.”

To tell the story of the trees, Lewis traveled to locations around the world to experience them firsthand. He studied the kopak tree while on a scientist friend’s bachelor party trip hunting for harpy eagle nests in the jungles of Peru. He also spent three days talking to researchers at the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research in Tucson, Arizona, where he encountered a cross-section of Prometheus, the famed 5,000-year-old Great Basin bristlecone pine felled for research in 1964. Once thought to be the world’s oldest living tree, Prometheus’ record-breaking age was only determined after it was cut down by counting its rings.

“You can read a tree ring in the same way you can read a book,” Lewis said, noting his trip to the Tucson lab opens his book’s first chapter. “The title of the chapter, which is somewhat provocative, is called ‘A Book Older Than God’ because presumably, if the Bible says that the Earth is 6,000 years old and we find a tree older than that, what does that mean?”

Being routinely surrounded by a wealth of different trees throughout the Huntington’s many gardens, Lewis says inspiration for the book was “somewhat organic” and calls the Huntington’s botanical staff his “secret weapon,” noting it employs some of the world’s foremost authorities on trees.

“When you’re trained as a historian, not as a scientist, you live in fear of making a terrible error because you’ve suddenly gotten out of your lane into somebody else’s — you’ve engaged in what a friend of mine calls ‘epistemic trespass,’” he said. “So, I’m proud of the fact that no one has yet pointed out any major errors in the book, even though I’m not a botanist.”

A critical success, “Twelve Trees” was included in The Guardian’s list of “Best Science and Nature Books of 2024,” Smithsonian magazine’s “Best Science Books of 2024,” and The Economist’s “Best Books of 2024.” It was also a finalist in the science category for the 2024 Los Angeles Times Book Prizes and was awarded the silver medal for nonfiction for the 2025 California Book Awards.

“Everybody loves trees,” Lewis said. “And if they don’t love trees, they need to understand more about them so they can learn to love them.”

Organized Chaos

Lewis’ expertise as a curator, success as an author, and passion for the natural world has taken him to far-flung regions of the world and led to a number of opportunities throughout his career that he couldn’t have predicted. He has had post-doctoral appointments at Oxford University, the Smithsonian, and the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society in Munich. He has given countless talks about his books and has been interviewed by several media outlets, including an NPR interview with Ari Shapiro for “Twelve Trees.” PBS flew him, along with his wife and two sons, to Hawaii in 2022 to appear in the documentary series “Human Footprint,” where he was interviewed about issues of nativeness and belonging — who gets to decide what belongs and why. Perhaps most unexpectedly, his work as a producer on a segment about women in aerospace for KCET’s “Blue Sky Metropolis” series garnered him an Emmy in 2020.

“I consider mine my lifetime achievement award,” he said of the surprise accolade. “I did so little for that, that I am a little embarrassed, but I’m not going to get rid of it. It’s a good talking point in my office.”

The diverse knowledge Lewis has acquired throughout his career has also led to invitations to serve on a number of committees. The expertise he has gained in the history of astronomy through his work at the Huntington earned him a spot on the committee for the new “Message in a Bottle” campaign with NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The campaign is an extension of the 1977 Golden Record project, in which phonograph records encapsulating life on Earth were launched with the Voyager spacecraft with the aim of facilitating communication with intelligent extraterrestrial lifeforms.

“The natural world is messy, and at the same time, we’ve tried so valiantly to organize it. Something about that combination of organizational tidiness and messiness is very interesting to me.”

He also currently serves as a member of the Species Survival Commission for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a network of scientists and experts that stands as the global authority on the status of the natural world and the measures needed to safeguard it. He holds a consultative and observational role with IUCN, serving as a Bird Red List Authority member and offering insight into the decline of species of which he has expertise.

“It’s an important vantage point to help shape the ways that we respond politically, logistically, and practically to a lot of environmental matters related to species decline, climate change, species resurrections, and so on,” he said.

For his fifth book, currently in progress, Lewis is embarking on a sweeping exploration of the historical, cultural, and ecological impact of the concept of extinction and the ways in which it has shaped our perspectives on life, death, and the future of the planet. Divided into four parts, “Lost: A Biocultural History of Extinction” examines extinction spanning from ancient myth to the new science of resurrection biology and some of the tens of thousands of species at risk today. Despite the heavy and often bleak subject matter, his excitement for the project is palpable.

“Who knew that writing about extinction could be so much fun?” Lewis said. “I’ve gotten to reach in lots of corners of the natural world and its practitioners in working on this book, and it’s such an important topic. It’s like a giant fever dream. It’s my best book yet.”

In keeping with the Darwinian ethos that he’s maintained throughout the winding course of his career, Lewis has been quick to acclimate to the added challenge of an ongoing illness in recent years, and, nearly 30 years on from when he first joined the Huntington, remains as busy as ever. His successes as an author and curator, and the many unique opportunities he has been presented, are the result of a mix of immense dedication and adaptability, his life echoing the same kind of “organizational tidiness and messiness” that shapes his love for the natural world.

“We’ve tried to group things into categories, but at the end of the day, everything is in the process of turning into something else,” he said. “You just can’t see the mechanisms at play — the wheels turn too finely. Selective pressures are constantly at work on organisms — mutation, genetic drift — all these things continually change. And that goes for us, too.”