The Unquenchable Thirst of AI

As AI grows at an exponential pace, Shaolei Ren’s breakthrough research is exposing the alarming environmental impact of Big Tech’s reliance on fresh water

By David Danelski | Photos by Stan Lim

S haolei Ren has an appreciation for water that many of us will never know.

During his early childhood in a small town in China, life flowed to the rhythm of tap water faucets that sputtered to life for just half an hour a day — a brief window for residents to fill buckets with their household’s daily supply.

Ren, an associate professor in UCR’s Marlan and Rosemary Bourns College of Engineering, is now one of the world’s leading experts on the growing consumption of scarce fresh water supplies by big technology companies, which rely on water to cool millions of servers in warehouse-sized data processing centers.

As Big Tech’s thirst increases with the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), Ren’s work has exposed the industry’s outsized water footprint while also finding ways to minimize its impact on communities already strapped for the precious resource. Previously, what was known about tech’s water consumption was murky at best.

In a 2023 breakthrough study, Ren and his graduate students studied GPT-3, one of the earlier language models behind OpenAI’s popular tool, Chat GPT. They found that a roughly two-week training program for GPT-3 in Microsoft’s state-of-the-art U.S. data centers consumed about 700,000 liters of fresh water. This figure would have tripled if training were done in Microsoft’s data centers in Asia, which are less efficient. In terms of the language model’s usage, they calculated that 30 or so user queries on GPT-3 consume about a half-liter, or around 17 ounces, of fresh water for data center cooling and electricity generation. Although the AI models today likely have better resource efficiency, per data released by Open AI in July 2025, ChatGPT users now collectively send more than 2.5 billion messages each day.

“In my experience, water was never an unlimited resource. But somehow, in the U.S., people often think of it as something we always have.”

“Every time you ask an AI chatbot a question, you are also consuming water,” Ren said. “AI doesn’t just require computing power; it needs cooling, and that cooling comes with a cost.”

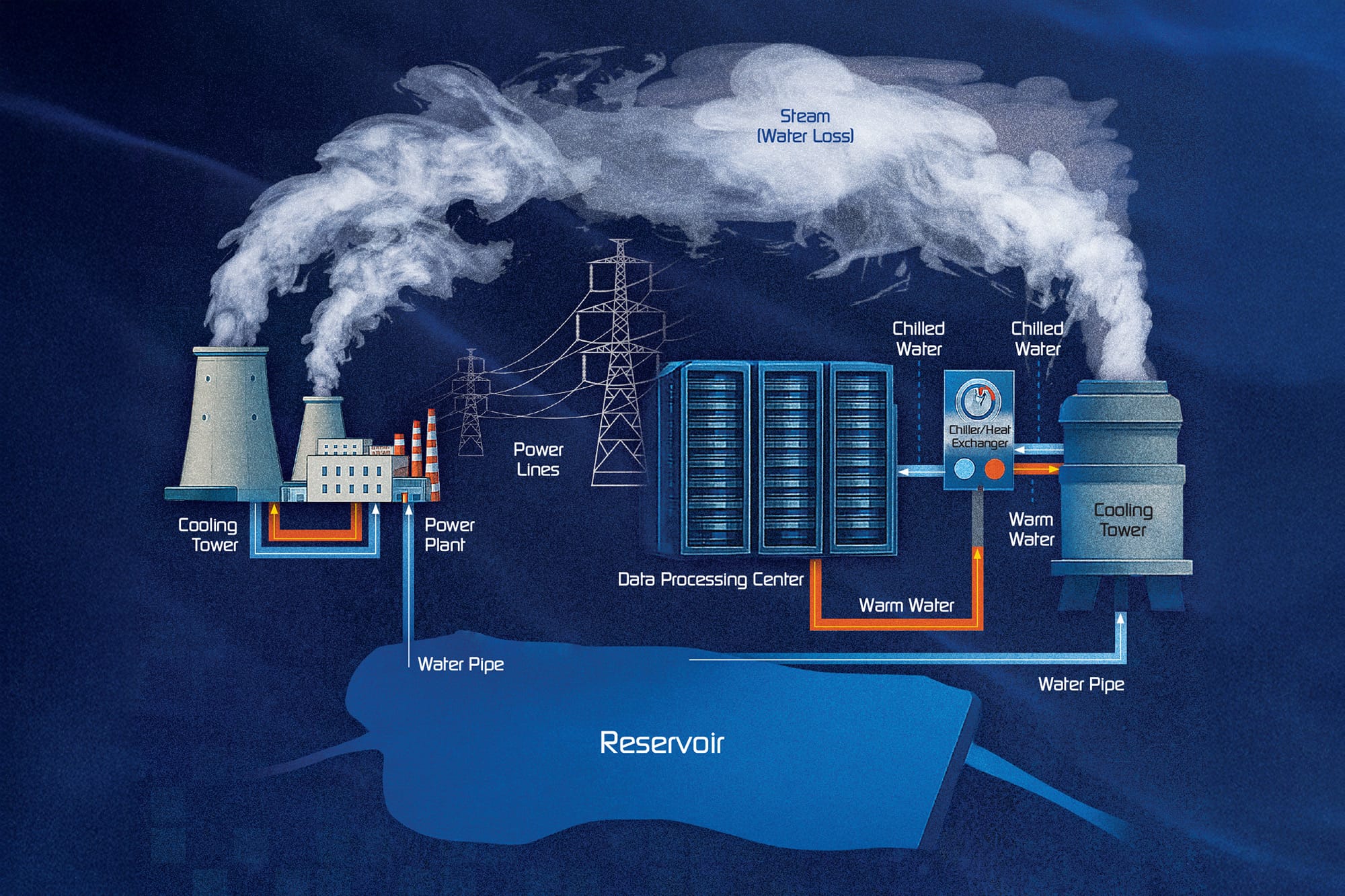

Ren explained that data processing centers consume water in two ways. First, the centers draw electricity from power plants that use large cooling towers that convert water into steam emitted into the atmosphere. Second, the hundreds of thousands of servers at the data centers must be kept cool as electricity moving through semiconductors continuously generates heat. Like power plants, this requires cooling systems that commonly consume water by converting it into steam.

“The cooling tower is an open loop, and that’s where the water will evaporate and remove the heat from the data center to the environment,” Ren said.

But there are ways to help mitigate water loss. Even small changes, like timing AI training during cooler hours, can reduce water lost to evaporation and make a big difference in avoiding wasteful usage, Ren said.

“We don’t water our lawns at noon because it’s inefficient,” he said. “Similarly, we shouldn’t train AI models when it’s hottest outside. Scheduling AI workloads for cooler parts of the day could significantly reduce water waste.”

Ren acknowledged that the need for his family to store tap water in buckets during his early childhood in Kang’erchengzhen, a town in the southwest part of Hebei Province where his father worked as a procurement specialist for a power plant, instilled a sense that water is a precious commodity that must be used wisely.

“In my experience, water was never an unlimited resource,” Ren said. “But somehow, in the U.S., people often think of it as something we always have.”

TSINGHUA OR BUST

After Ren’s 2023 paper was published, he found himself inundated with interview requests from journalists around the globe. He was asked to serve on a United Nations sustainability panel and found his work cited in water policy reports prepared by government agencies in the U.S. and Europe. Last fall, he gave a TED Talk about AI’s growing water footprint to an international audience in Vienna, Austria. But there was a time when Ren’s academic future was uncertain.

When Ren moved with his family to Beijing at age 6, he entered school without having attended kindergarten and showing little academic motivation, he said. As a junior high school student, he was drawn to computer game rooms in basements hidden in the city’s networks of small “hutong” alleyways.

“I was probably the only one in my class who spent most of their time playing computer games,” he said.

These computer games sparked an interest in computing that compelled Ren to teach himself proficiency in the personal computer operating system software of the time, including MS-DOS, Windows 3.1, and Windows 95. Still, his academics suffered in junior high, where students were ranked based on their test scores.

“My grade had about 360 students, and I was ranked at 344 in my first year. I remember that number very well,” Ren said.

College didn’t appear to be in his future and, if he didn’t improve, he would be placed in vocational school, he said.

“I didn’t have any plan for going to college. My parents were not college students, and they didn’t tell me anything about college. All I learned about college was from my peers,” Ren said.

By his third year of junior high, the influence of his hardworking peers inspired a remarkable transformation in Ren. He earned admission to a highly competitive high school where many students aspired to attend Tsinghua University, China’s prestigious technology institution in Beijing. Often referred to as the “MIT of China,” Tsinghua repeatedly ranks as Asia’s top university for engineering and computer science.

Ren became captivated by the idea of getting accepted into Tsinghua. When a headmaster asked students to list their top three college choices, Ren wrote down only Tsinghua. He rode his bicycle to school each morning and studied for hours each evening with no more time for computer games or other entertainment. At times, he couldn’t afford to buy the books he needed, so he found them in bookstores and studied there instead.

“There were some very big bookstores near where I lived, so every weekend, I remember, I went to bookstores to study for free,” he said.

Since he didn’t share the same hobbies, such as collecting sneakers, as some of his wealthier classmates, Ren wanted to prove that he could excel academically.

“That was maybe one motivation that kept pushing me to do well,” he said.

Ren excelled in the core subjects of Chinese, English, math, physics, and chemistry. He rose to the number-one ranked student in his high school in all but one exam. And, accordingly, he was offered a coveted spot in Tsinghua’s electronics and information engineering program.

Ren went on to receive a bachelor’s degree from Tsinghua, a master’s from Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and a doctorate from UCLA, all in electrical engineering. Along the way, he interned for Microsoft and lived in Issaquah, a small mountainside community near Microsoft headquarters less than 20 miles east of Seattle.

As an assistant professor at Florida International University, Ren’s early research focused on economic theory and wireless systems for video, audio, and text communication. He later switched to cloud computing and data center optimization research, with interdisciplinary interests in economics, energy consumption, and environmental impacts.

In 2012, while still in Florida, he found himself in search of a research area where he could make a difference. An idea sprouted when he noticed that landscape irrigation systems in Miami would turn on automatically during rainstorms when the plants didn’t need more water.

“I thought this was just a waste,” he said.

Ren considered delving into research to create algorithms to regulate irrigation systems based on the weather and the actual water needs of plants. A quick internet search, however, found other computer science scholars had already published several papers on this topic — the work had already been done. But then he thought, what about the other way around?

“Instead of computers for water, maybe water for computers,” he said. “It seemed like a crazy idea.”

A subsequent search found no academic research about the topic, but a blog written by an Amazon engineer confirmed water consumption was a major issue at data processing centers. Ren had found his niche.

Testing the Waters

Just a year later, Ren presented his first paper about water use at data centers at a conference in Germany. It detailed how tech companies could use water more efficiently by managing processing workloads at multiple centers while also accounting for the distance between centers and their individual energy use.

At the time, tech companies were racing to build data processing centers as more and more basic computing tasks moved from desktops and mainframes to the cloud. They also needed to process a growing number of internet search queries and online shopping orders, among various other demands. While other scholars zeroed in on Big Tech’s growing carbon footprint, Ren stood alone researching its water use.

His first grant application to the National Science Foundation to continue his water consumption research was rejected. But Ren persevered. His second application was funded, and his work moved forward with support from graduate students he could now hire to assist in his research.

“When we go to grocery stores, we check the prices before deciding which products to buy. But we’re not doing the same thing for AI models.”

In 2015, Ren re-entered the job market and landed at UCR as an assistant professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering; he is now an associate professor. He described joining the university as a great decision.

“You have a lot of freedom and flexibility to control the pace you do your research,” he said of working at UCR. “Sometimes you’re doing some risky research, and the review process could take two or three years. Just like our recent AI water-use paper, it took more than two years to get officially published.”

When that paper became the subject of international news coverage, including stories by BBC, The Wall Street Journal, CNBC, and The Washington Post, Ren faced a new challenge.

“I needed to learn how to speak with journalists,” he said. “They sometimes take our study out of context and put their own thoughts into it. But, of course, they bring this message to the public, letting more people be aware of this issue.”

Ren recently co-authored an IEEE Spectrum article with Amy Luers, who leads sustainability science and innovation at Microsoft, further clarifying AI’s water use and what can be done to minimize it.

“We often see polarized views on data centers’ water usage, so we try to be as objective as possible and as balanced as possible,” he said. “We can actually stand together because we share the facts.”

His goal is simply to make people aware of AI’s hidden costs.

“It is very important to make informed decisions,” Ren said. “When we go to grocery stores, we check the prices before deciding which products to buy. But we’re not doing the same thing for AI models, at least not comprehensively. So, understanding the cost and resource usage is just a very natural thing to me. Also, if we can save water at the same time, that’s a good thing.”

The Cost of Staying Cool

Data processing centers consume massive amounts of water in two ways:

First, they rely on power plants, which use steam to spin a turbine to generate electricity. That steam is then converted back into water inside a condenser by using cooler water withdrawn from a nearby source, like a lake or river. The cooler water heats up during this process and is then transferred to large cooling towers, where it is cooled by the air as it falls and collects in a basin. While the water collected by this process is recycled, a portion is lost each time through evaporation

Second, data centers employ a chilled water system, circulating water cooled by a chiller through pipes to absorb heat from their servers. The cooled water heated through this process is sent back to the chiller and transferred to a cooling tower, where some of it is also lost to evaporation.