Sister Missionary Position. Sister Hysterectoria. Sister Succuba.

At (literal) first blush, the names of the thousands of Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence across the globe are designed to elicit smiles and laughter. Yet according to Melissa M. Wilcox, a religious studies professor at the University of California, Riverside, behind the cheeky monikers lies a formidable brand of activism.

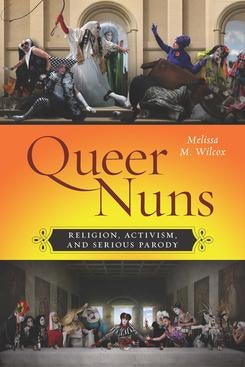

In her new book “Queer Nuns: Religion, Activism, and Serious Parody,” Wilcox chronicles the growth of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a religiously unaffiliated order of noncelibate nuns of all genders and sexualities that originated nearly 40 years ago.

“I’ve loved and been fascinated by the Sisters for as long as I can remember knowing who they were, and I’ve wanted to write about them for a really long time,” Wilcox said of the book, released this week by NYU Press. “People often think their numbers are smaller than they are, and scholars have tended to treat them as just another street theater group, but over and over again, they’ve shown up as part of the wallpaper in all kinds of studies of queer communities and HIV/AIDS, and queer communities and activism.”

“Queer Nuns,” she added, is an effort to finally bring the order out of the background and into the spotlight.

Drawing on aspects of drag and Roman Catholic imagery, the Sisters put a bold spin on grassroots organizing. As activists and fundraisers, they promote sexual health and the reduction of guilt and shame in LGBTQ and other marginalized groups — all while wearing habits and their signature white pancake makeup, of course.

The original house of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence was established in San Francisco in 1979. Its model, however, quickly spread to urban areas around the globe, including Toronto (1981), Sydney (1981), London (1990), and Paris (1990). Today, the Sisters’ online registry lists more than 65 houses in 10 countries.

The organization’s earliest members described themselves as “an order of gay men dedicated to the promulgation of universal joy and the expiation of stigmatic guilt,” with their order’s structure largely mimicking that of a traditional religious institution.

Much like would-be Catholic nuns must do, interested parties approach membership in a house in steps, first becoming aspirants, then postulants, novices, and finally fully professed Sisters.

They assume names that “share much in common with the time-honored drag tradition of incorporating witty, sometimes searing, and often sexual puns,” Wilcox wrote. And many houses offer activities like confession, although in this case it’s more likely to take place in a bar than a church.

Wilcox, who conducted formal interviews with 91 Sisters and interacted with many others, said a number of them reported feeling a calling to the Sisterhood similar to that of a traditional religious calling. Others were simply drawn to the Sisters’ commitment to service and social change.

As Wilcox noted, the Sisters’ strain of activism is perceived as a nonconfrontational, oftentimes campy form of resistance — and that’s a major part of what makes it so successful.

It’s their clever approach that inspired her to coin a new term, “serious parody,” to describe the Sisterly style of simultaneously critiquing and reclaiming the traditions of one of the LGBTQ community’s most outspoken opponents, the Roman Catholic Church.

“Serious parody, as I conceive of it, is a form of cultural protest in which a disempowered group parodies an oppressive cultural institution while simultaneously claiming for itself what it believes to be an equally good or superior enactment of one or more culturally respected aspects of that same institution,” Wilcox wrote.

“In the case of the Sisters, this means enacting parodies of Roman Catholic rituals and figures such as nuns and priests while also claiming in all seriousness to be nuns.”

Because the Sisters do, in fact, consider themselves nuns, Wilcox said it may be necessary to redefine the concept of what being a nun means. After all, the Sisters have long mirrored traditional nuns by acting as agents of change in their communities: appearing at pride parades, raising funds for refugees, and working to reduce the risks associated with unprotected sex and injection drug use, among other activities.

“For instance, in Las Vegas, the Sin Sity Sisters focus exclusively on HIV/AIDS services, raising an impressive amount of money each year for their program, which serves people of all genders and sexualities who are HIV-positive and cannot afford medication,” Wilcox explained. “Working directly with pharmacies and insurance companies, the Sisters’ AIDS Drug Assistance Program, or SADAP, pays for HIV medications for their clients.”

More importantly, the Sisters have continued to evolve as a grassroots organization. Going forward, Wilcox believes the order will embrace further diversification, both in terms of its membership and the causes it supports.

“The Sisters have always done activist and fundraising work,” she said. “Some houses and individual Sisters have begun responding to and participating in new movements like the Women’s Marches and Black Lives Matter protests.

“There’s a larger ethos among Sisters, and different Sisters take on different aspects of that ethos depending on what’s going on currently — and there’s no reason to believe that won’t continue.”

Wilcox currently holds the Holstein Family and Community Chair in Religious Studies at UCR, where her transdisciplinary research program focuses on gender studies and queer studies in religion.

Her previous books include “Coming Out in Christianity: Religion, Identity, and Community” (2003), “Sexuality and the World’s Religions” (2003), “Queer Women and Religious Individualism” (2009), and “Religion in Today’s World: Global Issues, Sociological Perspectives” (2013).