The United States border has seen an increase in families — primarily men with their children — and most recently a surge in unaccompanied minors traveling north from Central America through Mexico. They are fleeing gang violence, high homicide rates, and lack of economic opportunities. In some cases, such as in Guatemala, even hunger. According to the Pew Research Center, the U.S. Border Patrol apprehended nearly 100,000 migrants in February; this after apprehensions had fallen to about 16,000 in April 2020.

The Coronavirus pandemic contributed to the slow down, but the recent surge has caused politicians to visit the border and bring the issue to the forefront. Some blame the surge in migration on President Joe Biden’s reversal of Donald Trump’s immigration restrictions. Experts, though, attribute the increase in migration to the lack of economic prosperity due to the COVID-19 shutdown, as well as natural disasters such as November’s Hurricane Eta and Hurricane Iota. According to the American Red Cross, the hurricanes affected over six million people, displaced more than a half-million residents from Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, and have left about 250,000 still living in emergency shelters.

UC Riverside experts provide insight to the current situation at the U.S.-Mexico border:

Q: Is the United States less willing to take Central Americans as refugees because they come with less education? Less wealth? Is it a racial issue rather than a political issue? Or what should (or not) be the U.S.’s role in helping Central America?

A: Central American migrants — including asylum seekers and refugees — are indeed generally coming from economies with higher indices of poverty and lower levels of education than say, Mexico. But this is not the reason why the United States is less willing to take in refugees from Central America. The United States was granting less than 3% of Central American asylum applications under most of the Obama administration and these practices continued under the Trump administration. This will likely continue under the Biden administration, despite his efforts to appear to be taking a more humane approach on the issue.

To understand how Central Americans are being treated at the border we must look at both the immediate relative number of childhood arrivals, as well as the broader architecture of anti-migrant and anti-refugee policies since 1996. These policies were influenced by a constellation of think tanks and policy organizations founded by John Tanton, a Michigan-based doctor and eugenicist thinker who had a fanatical concern with the racial and ethnic makeup of the United States. He wanted to ensure that the United States maintained a clear Euro-American majority and subscribed to the idea that Western Europeans were genetically superior and more fit for becoming Americans and for democracy than people from Mexico.

Tanton’s organizations, the Federation for American Immigration Reform, the Center for Immigration Studies, and Numbers USA, formed out of fear of the United States passing another immigration bill like the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA), which provided amnesty for over 1 million undocumented migrants. They mistakenly argued that IRCA is what set the foundation for the shift toward greater Mexican immigration and the demographic transformation of places like Southern California in the 1990s, without considering the role of foreign policy in creating the very conditions that displaced people from the Mexican countryside well before the 1986 law went into effect.

Tanton’s organization went on a quest to prevent immigration reform that granted any form of amnesty to the undocumented — especially those from Mexico and other Spanish-speaking nations — from ever happening again. His organizations have had a hand in derailing several immigration reform proposals since 1996. But they are not content with simply preventing immigration reform from happening again. The second goal of these organizations was to create more restrictive immigration and asylum policies toward Mexico and by default other Latin American countries. The 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, for instance, was heavily influenced by Tanton’s eugenicist ideas and his organizations; it is the law that creates a series of mechanisms for preventing people from ever reaching a judge to present their asylum claim in the first place through the process of expedited removal.

The ideas in this law, as well as the ideas of deceased political scientist James Q. Wilson in his influential article in the New Yorker magazine, were foundational to the designing of Trump’s zero-tolerance policy that was aimed directly at Central American asylum seekers.

So yes, you could say that the last 30 years of immigration and refugee policy were largely about race, about keeping out those deemed racially unfit for American society and democracy from ever staying in the United States under conditions of equality and justice. The legal architecture used to deny asylum seekers from Central America could not be removed from the racial politics toward Mexicans that has defined the history of the Southwest for over 170 years.

If we want to live in a democracy that lives up to its domestic promise and global rhetoric of being the good guys after WWII, we should treat Central Americans and other refugees more fairly. However, we are still largely divided — 70 million people voted for Trump and most of his supporters have an affinity for his brand of neo-eugenics policies and harsh stances on immigration. Nonetheless, there is momentum from large sectors of society, many of whom are Latinos but also progressive whites, many African Americans and more recently Asians that want to see the United States under the current administration treat those that have been historically excluded and marginalized treated with greater dignity. The conflicts and division over these issues is not going away on these issues.

If the United States wants to reckon with the issue of Central American refugees, we must first confront the fact that we destabilized El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras throughout much of the 1980s when the U.S. was fighting guerrilla movements that wanted social and economic justice in the region. Accepting that we were wrong is the first step in doing something right for Central America and for Central Americans in the United States.

— Alfonso Gonzáles Toribio, associate professor of ethnic studies and director of the Latino and Latin American Studies Research Center

Q: How might COVID-19 be complicating the situation for unaccompanied children in terms of their physical and emotional wellbeing?

A: The plight of unaccompanied children in ‘normal’ times is difficult enough.

Leaving unstable environments, enduring harrowing journeys, and then ending up separated, alone, and confused in a foreign land is traumatic. COVID-19 has only heightened the trauma.

Now they face fear of infection with a deadly virus, being exposed to a much larger number of strangers, which will heighten their fear and anxiety. Children are thankfully less affected in general by serious COVID infection, but it does happen, especially in teenagers, who often make up a sizeable proportion of the minors crossing the border unaccompanied.

— Brigham C. Willis, MD, MEd, senior associate dean for Medical Education and professor of pediatrics

Q: Regarding the politics of the border crisis, how does the situation pose a challenge for the Biden administration? How might Republicans use the border crisis to take back Congress in the 2022 mid-term elections?

A: We obviously see the GOP already using the border to ramp up criticisms of the Biden administration — Sen. Ted Cruz just did his photo ops there, for example. And the GOP aren’t going to let up on that; it’s been an issue that has worked for them — in the sense that it has mobilized support for them — for very many years in both state and federal politics. In fact, you could say it has been an issue that the GOP have used in campaigns for several decades.

In California, for example, we saw the propositions as far back as the 1990s that were built around mobilization on the issue by then-Gov. Pete Wilson and the GOP. What is noticeable is that the issues seems to be raised and then re-raised as an issue all the time, but there aren’t many solutions being offered — even by those who raise the issue. And there are generally ever fewer solutions produced even by those who raise it once they are in power.

A cynic might note that this is the best of all worlds for candidates. It is one that helps generate votes and donations. But it’s never an issue that is resolved, and so it is an issue that can be brought out time and time again at election time. A less cynical view might be that immigration is an inherently difficult issue, not open to easy solutions but requires some thought and multiple kinds of steps.

—Shaun Bowler, political scientist and dean of the Graduate Division

Q: Do you expect this border situation will have any negative ramifications for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy?

A: I see DACA as a separate issue from the recent wave of refugees from Central America.

DACA recipients are a very particular cross-section of the immigrant community. In order to receive DACA, you have to have graduated from a U.S. high school or have a GED; furthermore, you have to fulfill requirements that demonstrate that you are of “good moral character.”

The only negative ramification is if people were to conflate the policy that pertains to DACA recipients with our current refugee policy, which is shifting under the Biden administration.

— Jennifer Nájera, associate professor and chair of the Department of Ethnic Studies

Q: The GOP asserts that the influx of immigrants at the border is proof that the previous administration's comparatively aggressive border tactics were effective. How do you address that assertion?

A: I would suggest they check their data. The net number of foreign migrants to the US dropped significantly in 2015 and 2016, during the last two years of the Obama administration.

The Trump presidency was very good at performing an aggressive stance and promising a wall, but on the whole the numbers of foreign migrants to the U.S. were relatively stable in 2017 and 2018.

What we are seeing at the border is a consequence of a confluence of factors. The Biden administration's signaling that it will have more welcoming immigration policies is really only one of those factors, but I would venture that it is not necessarily the driving one. The fact is that in both Guatemala and Honduras, poverty is a main driver of migration, in concert with gang violence and paramilitary violence. And two hurricanes in 2020 laid waste to both countries — especially in the poorer areas of the country. Add to that the economic fall out of the pandemic and you have a powder keg of circumstances.

— Juliette Levy, associate professor, Department of History

Q: What political dynamics in Mexico and Central America are driving the exodus?

A: In addition to the structural economic problems associated with underdevelopment, there are two additional factors that might be contributing to the recent border crossings. First, both Mexico and Central American countries suffer from very high levels of violent crime, resulting from the operations of violent youth gangs (maras) and drug trafficking organizations.

It is estimated that El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras account for about 4 1/2% of homicides worldwide despite only having about one-half percent of the world's population. This pushes many desperate Central Americans to try to escape to the United States, perceived as a safe haven.

Second, many Central American governments are very corrupt. Some of the development aid received from the United States and other wealthy countries has been diverted by corrupt politicians for other purposes (e.g., personal enrichment). Government leaders in those countries also have links to criminal organizations. For instance, a court in the United States just sentenced the brother of the Honduran president to life in prison for smuggling drugs into the United States. A combination of state weakness, corruption, high criminality, and economic desperation creates a sense of hopelessness among people in Central America and Mexico, which pushes them to initiate the risky journey toward the United States.

— Miguel Carreras, associate professor, Department of Political Science

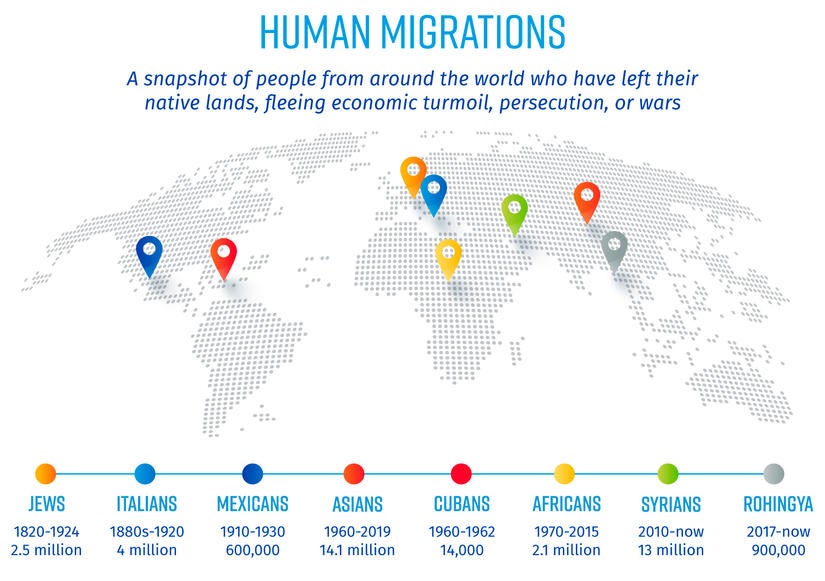

The world’s history has been marked by human migrations — and continues to do so. Here is a chronological snapshot of people from around the world who have left their native lands, fleeing economic turmoil, persecution, or wars.

Jews

1820-1924: More than 2.5 million came to the U.S.; more than 6 million were murdered in European countries between 1941-1945. This genocide is what we know as the Holocaust

Italians

1880s-1920: 4 million came to the U.S. fleeing poverty, diseases and natural disasters

Mexicans

1910-1940s: 600,000 fled the Mexican Revolution; in the 1940s 5 million were recruited by the U.S. as contract workers, known as Braceros

Asians

1960-2019: 14.1 million Asians now live in the U.S.; majority of the residents come from India, China and the Philippines

Cubans

1960-1962: “Operation Pedro Pan” allowed parents to send 14,000 unaccompanied children to the U.S. The country was in turmoil, a consequence of the Cold War

Africans

1970-2015: 2.1 million Africans now live in the U.S.; majority of the residents come from Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, and Eritrea

Syrians

2010-now: More than 13 million displaced; more than 5 million now live in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan

Rohingya

2017-now: 900,000 living in overcrowded camps in Bangladesh; an estimated 600,000 remain in Rakhine State, Myanmar and are subject to government persecution and violence