ALUMNI PROFILE

THE POET

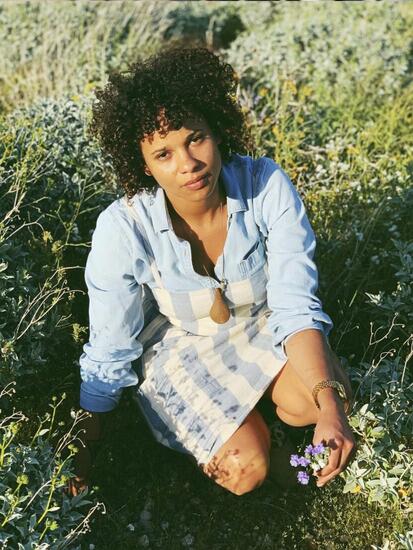

For Jasmine Elizabeth Smith, there’s power in poetry as advocacy

By Jessica Weber

asmine Elizabeth Smith has been drawn to poetry as far back as she can remember. Her first collection of poems took the form of a small, disheveled journal she made at around age 7, its pages containing frenetic scribbles of prose and verse.

“I told my mother I was a poet without understanding what poetry even was at that age. But somehow, I was able to associate it with a strong sense of emotion and sound and bouts of crying,” she said.

Smith, who graduated from the UCR creative writing MFA program in 2019, has now seen her poetry published in outlets including Black Renaissance Noir, World Literature Today, POETRY, and LA Review of Books, and has garnered several fellowships. Currently, Smith is a fellow of Cave Canem, a foundation dedicated to amplifying the voices of African American poets; and the Black Earth Institute, an arts organization focused on issues of social justice and environmental concerns.

This year also saw the publication of her first official poetry collection, what she calls a “love letter” to her native Oklahoma. Winner of the 2021 Georgia Poetry Prize, Smith’s debut collection “South Flight” served as her thesis while a graduate student at UCR and was published by the University of Georgia Press in February. Told in the form of letters, two lovers separated in the wake of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 hold imagined conversations with blues musicians and the ghosts of Greenwood — the prosperous Black neighborhood destroyed during the attack — as they contend with their opposing choices to stay or leave Tulsa.

“I remember bringing up the Tulsa Race Massacre in a high school history class in Oklahoma and being shut down — no one wanted to talk about it,” Smith said. “I realized the discomfort of the teacher, who did not want to even acknowledge that this happened, and that it was being hidden within the culture of Oklahoma as well. It was a travesty, not only that an event like this could happen but also its erasure from history.”

A desire to push back against this kind of erasure was the impetus for “South Flight,” and a common thread between much of Smith’s poetic work. Her interests lie in the margins of history, she said, and exploring the stories that have been left out, particularly within the Black diaspora. Smith is also motivated by the ways poetry can be used as a research intervention, challenging the unreliability and bias of popular historical narratives, and more broadly, how poetry can be used as an agent for activism and social change.

“Poets are in this space unconstrained by logic — they’re able to take these associative leaps, to daydream and think about what the future of liberation will look like,” she said. “Oftentimes, just giving something a voice is one of the first steps to social change.”

Smith’s poetry also explores the Black diaspora in various historical contexts to speak to contemporary political, social, and even ecological concerns. Upcoming projects focus on the histories of Black cowboys in the West and the Jonestown Massacre. In her forthcoming collection “Park,” Smith aims to interrogate what it means to be a Black woman navigating outdoor recreation spaces. Funded by the Black Earth Institute, the project will see her completing several hikes in Yosemite National Park while also doing archival research on the Black Buffalo soldiers who served as some of the first park and backcountry rangers.

Smith’s passion for poetry and advocacy has also extended to teaching. While a graduate student at UCR, Smith taught middle school students in Beaumont and brought arts advocacy to schools through programs in the Inland Empire. She also served as a district lead for the federally funded initiative “Along the Chaparral.” Headed by Allison Hedge Coke, distinguished professor of creative writing, the project involved working with area K-12 students to memorialize veterans interred at the Riverside National Cemetery. She now teaches English at the Bush School in Seattle, covering a range of topics including ecological literature, Afrofuturism, and sustainability.

Smith credits the community of support she found at UCR, through faculty mentorship and relationships formed with her peers, in finding her path as a poet. In particular, she credits Hedge Coke, who served as her thesis advisor, in helping bring “South Flight” to light. She encourages aspiring poets to find their own community and focus on writing what really moves them, not what they think is expected of them.

“Particularly with writers of color, there’s a lot of pressure to be the poet of witness or the activist poet,” Smith said. “I think you can still look in the peripheral but resist this inclination around performative suffering. Write the things that both bring you joy and that you are passionate about, but try not to let anyone dictate what that is.”

Return to UCR Magazine: Fall 2022