UCR, STYLE, AND JACQUELINE NORMAN

Jacqueline Norman has been wandering UCR’s campus since childhood. Now, she’s charged with preserving its architectural history.

By John Warren | Photos by Stan Lim

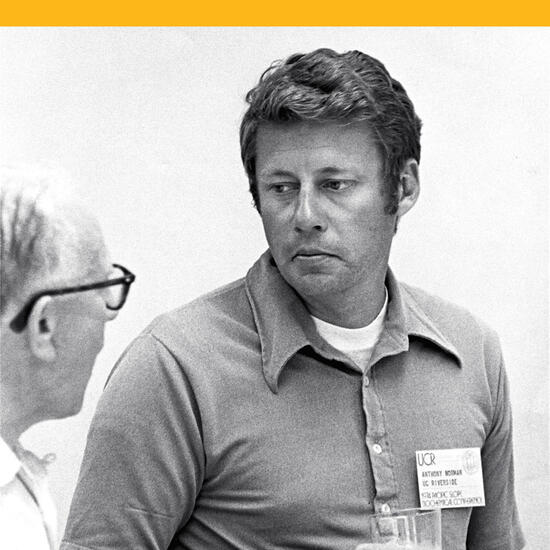

I t’s hard to say where Tony Norman’s lab was, standing in Boyce Hall today. Norman, who was a renowned biochemist and an early progenitor of Vitamin D, had a lab adjoining that of his wife, Helen Henry, on the fifth floor of Boyce. Here his daughters Jacqueline and Thea played in the 1970s and ’80s, filling beakers and test tubes with colored water and placing them on windowsills to watch refracted light dance.

Today on the fifth floor of Boyce, there are halls where walls were, and walls where walls weren’t. Norman’s onetime lab space is lost to decades of reinvention. The space today is a labyrinth of drywall — long, narrow, windowless passages marked by an occasional locked door. It’s not a space where one would expect a young person to be inspired. But the UC Riverside campus where Jacqueline roller-skated as a child is the church for what would become her religion: architecture.

“Even before I was aware of the concept of architecture, this is where I spent all my time,” Jacqueline Norman said recently, standing in one of her favorite spots on campus, the courtyard outside University Theater. “As a girl, I had a distinct idea this campus was special. I knew I liked being here,” she said. “These buildings formed my awareness of architecture; they sewed some seed in me about the idea of ‘place-making’ and how powerful and important such an act might be.”

Today, Norman is UCR’s campus architect: In her role — or, in her interpretation of the role — she is the steward of UCR’s architectural history, the gatekeeper who ensures continuity between old and new. Technically, the group she leads manages the planning, design, and construction of new campus buildings, but that characterization doesn’t do justice to the intensity of her gaze.

Of the comprehensive rebuilding of the Barn entertainment complex, she says: “I fought against a nostalgic Disneyland-like re-creation. New buildings shouldn’t try to pretend to be old buildings.”

As a student at Riverside Polytechnic High School, Norman visited the Salk Institute at UC San Diego and recalls first seeing the Louis Kahn masterwork “a holy moment.” After college, she studied and worked for more than 10 years at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin, an architect’s Mecca. In 2009 she took a job at UCR, becoming campus architect several years later. The masterworks for Norman and her team include the Student Success Center, the Multidisciplinary Research Building, or MRB, the south building of the Student Recreation Center, or SRC, and the Dundee-Glasgow residential dining complex.

Norman, 53, is willowy and favors long skirts and heeled boots, her face framed by ample black-gray locks. Her sentences are sprinkled with phrases such as “bris de soleil” and “articulated brickwork” uttered without pretense. Architecture is precision, as is the language used to describe it.

A casual observer might opt for “nondescript” to describe Aberdeen-Inverness, the original campus dormitory building. But Norman sees something else: “Every part of the facade is doing something important. It almost looks like music. There is a cadence; syncopation in the fins and shadows.”

Asked what she appreciates about the space outside University Theater, she says: “The fluidity and expansiveness of the space in the overall area, created by the multiple levels and the way the Olmstead buildings frame the views in all directions — in particular how the Olmstead office wing bridge creates a dynamic portal into campus. The buildings are inspired by the topography and it’s wonderfully dynamic.”

UCR’s buildings, old and new, might be considered sparse by a definition that isn’t Norman’s

“As a girl, I had a distinct idea this campus was special. I knew I liked being here. These buildings formed my awareness of architecture.” — Norman

“There is a place for ornamentation. But it needs to be careful, not dripping.” Buildings, she said, “should not look like a frosted cake.”

UCR’s original architecture is the midcentury modernism en vogue during the post-World War II “education explosion,” when the University of California system rapidly expanded. It’s the “form follows function” style many campuses have sacrificed to a bulldozer’s blade. Modernism is far divorced from the university architecture that has remained or come back into style; the Neo-Classical style of Harvard Yard, or the Gothic Revival architecture of any number of university buildings named “Old Main.” What binds UCR’s original 1950s buildings to the more recent ones is a “continuity of ideas,” Norman said. And it’s the harsh Inland Empire sun. The UCR campus was built in the 1950s to both embrace and deflect its desert environment

On Webber, one of the campus quad’s original circa-1954 buildings, there are screen-shading windows and porticos on the west side. Even today, any new building must have similar shading on its western exposure. The five-year-old MRB has sun-shielded arcades, same as the Rivera Library, its dramatic covered, arched walkway having once drawn the attention of Ansel Adams’ lens. On MRB, look closely at the articulated brickwork; it evokes the brickwork on the side of 1960s-era Pierce Hall.

“What you get from buildings Jacqueline has stewarded is a continuing expression of the clean aesthetic of the campus’ core,” said Drew Hecht, Norman’s colleague and UCR’s director of project management. Like with the older midcentury modern buildings, Hecht said Norman’s projects “have a very understated elegance that comes from simplicity.”

Frank Lloyd Wright once said, “The mother art is architecture,” and Norman argues convincingly that the bright-white facades, horizontal bands of glass, and gleaming metal framework on UCR’s campus are art, and that the art is in the subtlety. You may have never known the Watkins breezeway is like a sundial — you can tell what time of day it is from which holes the sun is shining through. In MRB, the interior concrete isn’t just concrete — it’s throwback “board-form” concrete; note the striations visible in the sweeping atrium.

Hecht recalls being in the room recently with Norman and a would-be contract architect who aimed to imprint UCR with his vision.

“She very diplomatically but firmly pointed him back to the design guidelines and suggested he study them,” he said.

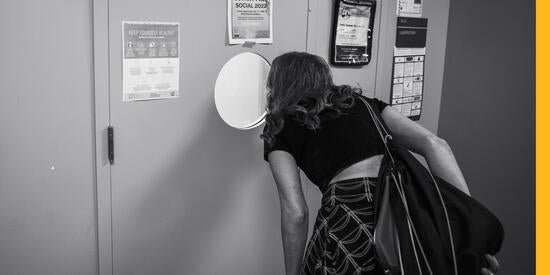

On a recent tour of Boyce, Norman, who lives in what was her late father’s home, paused before a yellowed poster in another labyrinth-like hallway. The poster reads “Vitamin D Nutritional Policy Needs a Worldwide Vision for the Future.” The researchers’ names: Anthony Norman and Helen Henry. She marveled that it still hangs.

“This runs deep with Jacqueline,” Hecht said. “You can’t underestimate the power of place and connection to home. It’s unique to our campus.”

“Every part of the facade is doing something important. It almost looks like music. There is a cadence; syncopation in the fins and shadows.” — Norman