ALUMNI PROFILE

The Call of the Wild

Among the first women in her field, biologist Margaret Merritt has dedicated her career to the research and management of fish and wildlife in Alaska

By Jessica Weber

W hile trekking through the frigid, unspoiled wilds of Alaska may seem daunting to many, San Diego native Margaret “Peggy” Merritt didn’t hesitate at the chance to become a field biologist in the far-flung state. In fact, she instantly felt right at home, spending the better part of four decades helping to study and manage fish and game across the vast and varied landscapes of “The Last Frontier.”

Always an outdoor enthusiast, Merritt earned a bachelor’s degree in biology at UCR in 1974 and a master’s in biology and ecology from Utah State University. Job opportunities proved scarce after graduate school, however, so the then 25-year-old decided to use the free time to visit a friend in Alaska. On her second day in town, she walked into a fish and game office and asked if there were any job openings.

“Two biologists came out and interviewed me, and I was offered two jobs, starting immediately,” Merritt said. “I selected one, and that started me on my career with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game for the next several decades.”

Merritt’s prolific career as a field biologist has seen her charged with a wide range of projects across Alaska, including early life history studies of chum salmon while living in an Iñupiat coastal village in the Arctic, moose surveys in Southcentral Alaska, chinook salmon investigations on the Yukon River, king crab index fishing in the Lower Cook Inlet, and assessment of Arctic grayling in rivers on the Seward Peninsula.

“The mission of the department includes the management of fish and game for the people’s benefit according to the sustained yield principle,” she said. “And to do that, you have to monitor the population dynamics of animals as well as the strategic behavior of people, who are predators in the vast ecosystem.”

While Merritt is passionate about her work, she said it’s not for the faint of heart, noting more biologists have died in the line of duty than Alaska State Troopers. She herself has experienced a few close calls, including nearly being crushed by ice from a calving glacier and flying blind in a snowstorm. In one incident, her colleague lost control of their skiff and she was tossed into the icy waters of the Chuckchi Sea, barely escaping entanglement in fishing nets. While they managed to get to shore, she said they were then forced to cross a river to get back to their camp on the opposite side.

“I swam across, and I called to my comrade to swim, and that’s when he said, ‘I can’t swim,’” Merritt said, noting she was able to retrieve him by putting him in a hold she had learned in a lifesaving course at UCR. “I’d swam across the river three times and somehow made it to my tent, and then I went into violent shivering thermogenesis. A couple days later, a rescue plane came and got us. We were survivors!”

Merritt stresses the importance of preparedness when working in Alaska’s unpredictable and expansive wilderness and that a lot had to be learned outside of the classroom — things like small engine repair, operating boats and firearms, bear safety, and how to read the snow and waterways. Even so, as one of the few women in fish and game at the time, she said her strength and ability was sometimes questioned, noting she was the first woman to tackle many field assignments during her career.

“At one job in particular, my presence was challenged by colleagues because it frustrated their vision of what a stable workplace looks like,” she said. “I always felt a lot of pressure to perform excellently because I felt other women would be judged by my performance.”

Despite being underestimated at times, Merritt excelled in her career, continuing field research even while pregnant with her daughter. Following the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, she was called back from maternity leave to serve as the research supervisor overseeing the sport fish program across the Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim region, an assignment that grew to encompass about 85% of Alaska’s landmass. During her 12 years in the role, she earned a doctorate in fisheries from the University of Alaska Fairbanks and went on to teach four courses part time as an adjunct associate professor of fisheries at the university for 10 years.

“I believe that I left the region in better shape than I found it, and I’m proud to have turned the helm over to a younger generation,” said Merritt, who left the department in 2001.

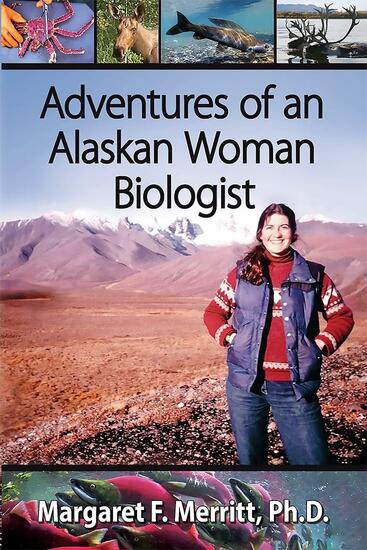

Merritt transitioned to a career in consulting, working on research and resource management projects for federal, state, and local governments as well as private nonprofits until 2015. Now retired, her latest adventure has been becoming an author. In addition to two historical biographies, Merritt recently authored “Adventures of an Alaskan Woman Biologist,” a memoir she was encouraged to write by her daughter. She is currently busy touring her book and giving talks, many to future fish and wildlife biologists at universities around the country.

“I wrote the book to share my outdoor experiences and to acquaint people with the wild animals and research methods used to study them,” she said. “But also, to encourage people to persevere in attaining their goals, especially women in male-dominated fields. I think that as more women scientists write about their experiences, more women will be inspired to become field biologists.”

Return to UCR Magazine: Fall 2023