OFFICE HOURS

Staring at the Sun and Moon

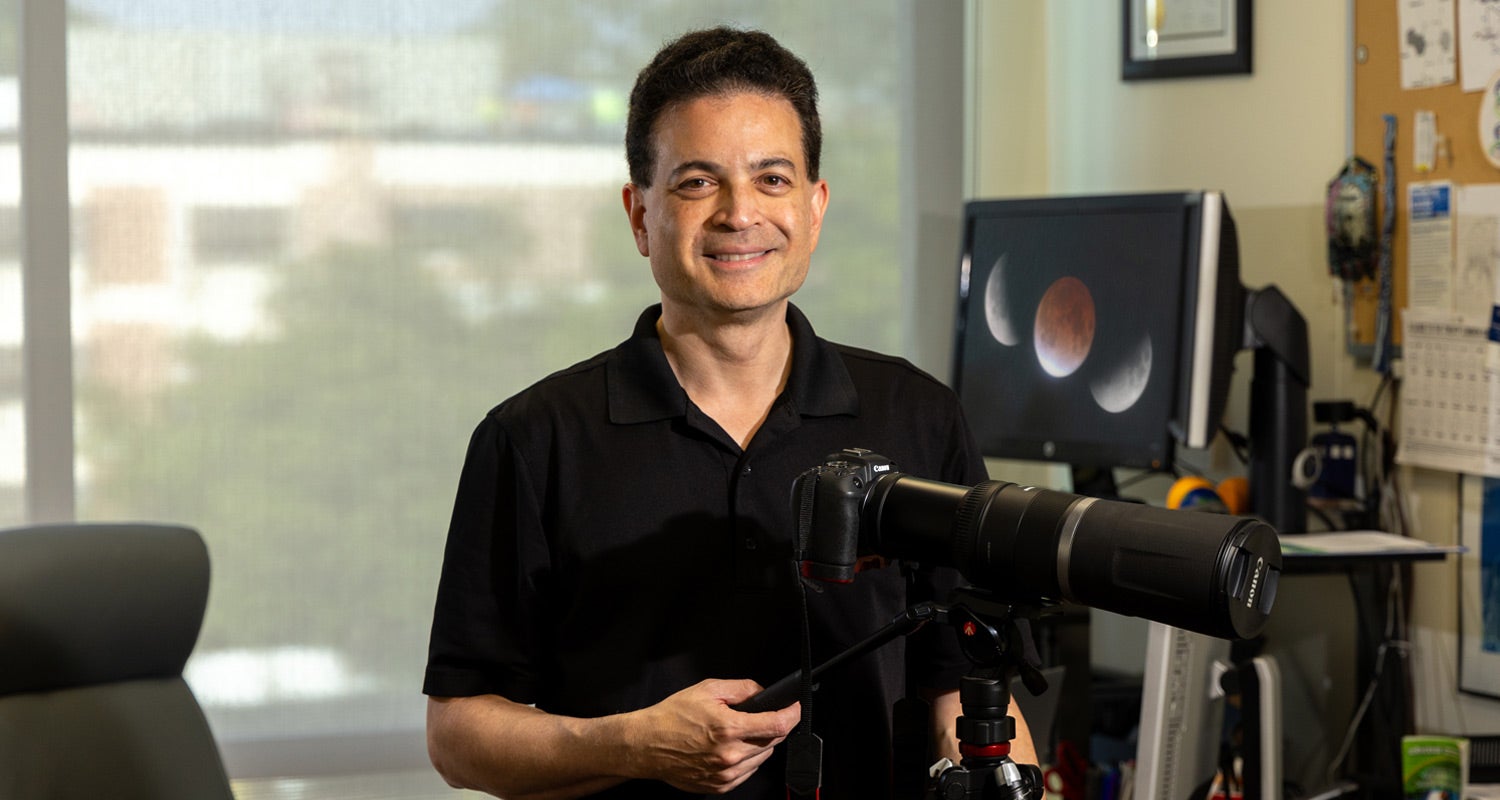

Geneticist Morris Maduro’s work focuses on the building blocks of life, but his hobby is chasing eclipses

By Imran Ghori | Photos By Stan Lim

Morris Maduro is often peering through microscopes at tiny worms, some of the smallest organisms on Earth, as part of his research. But in his personal time, the geneticist gazes through a telescope or a photo lens at the skies above hoping to capture pictures of lunar and solar eclipses. In fact, his second-floor office in UCR’s Genomics Building features several framed photographs of the eclipses he’s witnessed over the last 20 years.

Maduro first became fascinated with eclipses as a 9-year-old growing up in Edmonton, Alberta, in 1979, when a total solar eclipse became visible over North America. He asked his father if they could go to Montana where the center line would be and the umbra, or full shadow of the moon, would be visible. But his father wasn’t prepared to drive hundreds of miles in the dead of winter, so they watched it from Edmonton, where the sun was 93% covered.

Maduro, a professor of biology at UCR, soon became enamored with lunar and solar eclipses. He described it as a dance between the sun and moon that brings them into occasional alignment. He was also drawn by the scientific precision with which astronomers, going back for hundreds of years, could know exactly when and where an eclipse would appear.

“Our ability to predict and understand the natural world to that degree, coupled with the rarity and beauty of both solar and lunar eclipses, really got me interested in it,” he said. “That was the first science I fell in love with.”

Maduro began learning more about eclipses and tracked additional ones as a teenager. He started taking pictures with a “crummy” analog film camera and said he didn’t have decent photography equipment for a long time. As a postdoctoral scholar at UC Santa Barbara in the late 1990s, Maduro set his sights on finally seeing a total solar eclipse.

That opportunity came in February 1998 while on his honeymoon in Aruba with his wife, Gina Broitman-Maduro, who is now an associate research specialist in his lab at UCR. He’s since seen two more total solar eclipses, from Turkey in 1999 and Wyoming in 2017, and plans to be in Dallas in April 2024 for the next one. Despite his passion for astronomy, Maduro never considered making a career of it.

“As a hobbyist, you’re free to explore how much you want,” he said. Maduro earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics but switched to biology for his doctorate, both of which he received at the University of Alberta in Canada. He became interested in the genetics of the nervous system, leading him to a postdoctoral fellowship studying embryos in the lab of Joel Rothman, director of the Biomolecular Science and Engineering program at UC Santa Barbara.

“This is frontier science, figuring out how genes work,” he said. “We can take model systems, like worms or flies, and we can use the tools of genetics to understand how they develop.”

Maduro joined UCR in 2003 and is now the chair of the Department of Molecular, Cell, and Systems Biology. He has studied microscopic worms called nematodes for more than two decades, focusing on C. elegans, used frequently as a model to study how genes orchestrate development because of its small size and ease of cultivation in the lab. His lab has long studied how transcription factors — proteins that activate the expression of genes — work in early animal embryos.

Last year, he and Broitman-Maduro published a paper on how C. angaria, a species related to C. elegans, develops its gut, until then a mystery since the genes responsible for specifying the gut in C. elegans are absent in other nematodes. They found that a simpler gene network seems to be involved in specifying the gut in C. angaria, a related species to C. elegans. Their work suggests that the network in C. elegans was duplicated and expanded to make one that is more complicated. The pair are now investigating why C. elegans would need a more complicated gene network to specify the gut.

Despite the seriousness of his work, Maduro likes to have fun with it. Since 2005, he and a colleague have put together a comedy show for a regular gathering of C. elegans researchers that takes place at UCLA. “The Worm Show” features PowerPoint gags, parody songs, skits, and other bits. At one of them, he presented his doctoral thesis in the voice of Yoda. Maduro takes that same approach to his classroom and meetings, trying to infuse levity where he can.

“I generally try to bring a little bit of laughter to just about everything I do,” he said.

Return to UCR Magazine: Fall 2023