A Love Letter to Riverside

Ron Loveridge, UCR’s longest-serving professor, has dedicated his career in education and politics to creating a better Riverside

By David Danelski

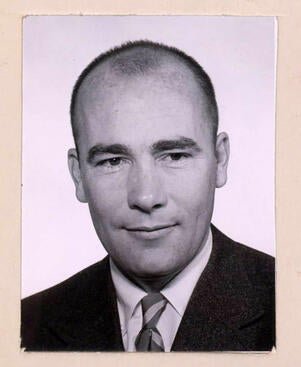

R on Loveridge’s first glimpse of Riverside came in 1964 from a passenger seat of a helicopter that had ferried him from the Los Angeles airport to a landing pad near Riverside’s Fairmount Park. Walking through the park, designed some 50 years earlier by the famed Olmsted Brothers, Loveridge admired the stately trees reflecting on Lake Evans and the blending of natural beauty with practical functionality. The people of Riverside care about this place, he thought.

The then-26-year-old Stanford doctoral graduate had a life-changing decision to make. Should he accept a position as a political scientist at the nation’s oldest public university, North Carolina at Chapel Hill? Or should he take a similar role at the fledgling University of California, Riverside, established just a decade earlier?

On a visit to the campus, Loveridge dined with UCR’s founding faculty members. He liked the small campus — serving about 3,500 students at the time — finding it reminiscent of his undergraduate days at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California. But what sealed the deal was a long, persuasive letter from UCR professor and political scientist Francis “Hank” Carney that he received following his visit.

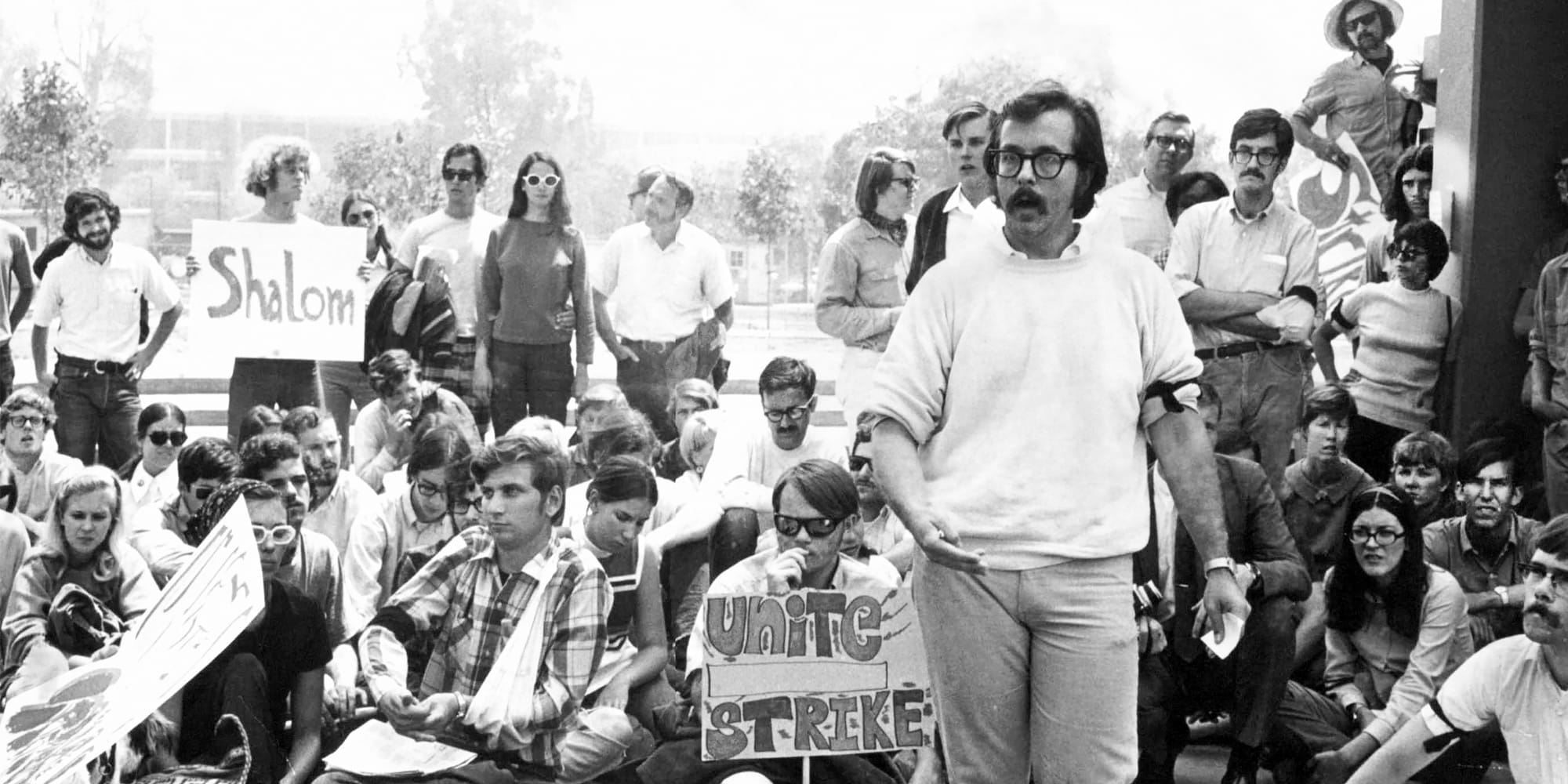

Loveridge arrived at UCR on a hot summer day in 1965. He parked his Volvo near the humanities building and got a parking ticket, even though the campus appeared to be deserted. He remembers those early years as framed by a backdrop of student protests for civil and women’s rights and opposition to the Vietnam War.

“I came across a student and asked her, ‘Why are you going to the protest?’” he recalled. “She looked at me and said, ‘If I don’t go, what would I tell my grandchildren?’”

At age 84, Loveridge continues to teach at UCR nearly 60 years later. He is now the university’s longest-serving faculty member.

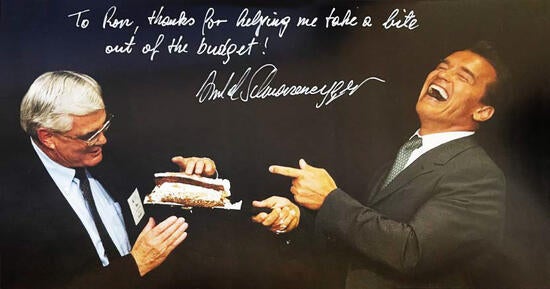

Even with his six-decade tenure on campus, Loveridge is best known for his storied political career. With university approval, he served on the Riverside City Council for 14 years and then as mayor of Riverside for another 20. Through it all, Loveridge continued his work as a political science professor, teaching seminars on state and local government while on leave from UCR. As a professor, he brought his firsthand political experience to the classroom and his students into the corridors of government. By his own count, he helped some 3,000 UCR students secure internships in local, regional, state, and federal government.

While other UC campuses battled their host cities in land-use disputes, Loveridge fostered collaboration between Riverside and UCR. In the 1990s, for example, city support for the construction of the University Village mall near campus came with a requirement that the mall’s movie theaters double as classrooms. Under his watch, the UCR California Museum of Photography and the Barbara and Art Culver Center of the Arts became part of the fabric of a revitalized downtown.

Loveridge’s political journey had humble roots, helping his mother, Doris, run for a school board seat by distributing fliers. As a high school student in Concord, California, Loveridge fondly remembers discussing school policies with his mother as she washed and he dried the dishes every evening. As the elected student body president at the University of the Pacific, Loveridge got called to the office of university president Robert E. Burns for holding forums that questioned the small university’s disproportional emphasis on football.

“Loveridge, what the hell are you doing?” he recalled Burns asking. “How dare you mess with football!”

Shortly after coming to UCR in 1965, Loveridge joined an urban coalition committee that sought solutions following the Watts riots that had occurred in summer. The following year, Loveridge took one of his classes to what he called the “political science laboratory” — the world beyond campus across the 60 and 215 freeway — to a campaign stop by gubernatorial candidate Ronald Reagan at an abandoned car dealership on University Avenue. Then famous as a movie and television star, the future president railed against student protestors at Berkeley and elsewhere, describing them as extreme radicals who needed to be dealt with harshly. Loveridge didn’t agree with Reagan but found him to be an articulate and captivating speaker.

“I’m standing in the back as he spoke, and some woman next to me rolled up her sleeve and said, ‘Look, goosebumps,’” he said.

In 1968, Professor Carney, now good friends with Loveridge, served as the Riverside County chair of Bobby Kennedy’s presidential campaign. “Personally and emotionally committed” to the Kennedy campaign, Loveridge watched Kennedy’s motorcade drive through Riverside’s East Side as people cheered before the candidate spoke to a packed audience at the Riverside Auditorium. After the speech, Loveridge and his wife Marsha met Bobby and Ethel Kennedy in front of the Mission Inn. Bobby Kennedy reached out and shook Marsha’s hand and wished her luck. Just days later, Kennedy won the pivotal California primary but was assassinated after finishing his victory speech at a Los Angeles hotel.

“So, our last images of Bobby Kennedy are those of the Mission Inn and him reaching out his hand,” Loveridge recalled in a UCR oral history project from the 1990s.

The tragic event did not leave him disillusioned — far from it. In the 1970s, after moving to a home near Mount Rubidoux in downtown Riverside, he found the city’s leadership lacking. The City Council, for instance, had voted to remove downtown parking meters but left up the unsightly metal poles. The downtown mall was all but dead, except for a few restaurants “that you probably didn’t want to go to,” he said. So, in 1979, he ran for the City Council seat that serves the downtown area. The professor-turned-candidate knocked on some 4,000 doors and got an education he didn’t quite expect.

“You’re essentially tutored at every single door that you knock on,” he said. “You’re talking to people, their families, and they have hopes and notions about what makes a good neighborhood and what makes a good city.”

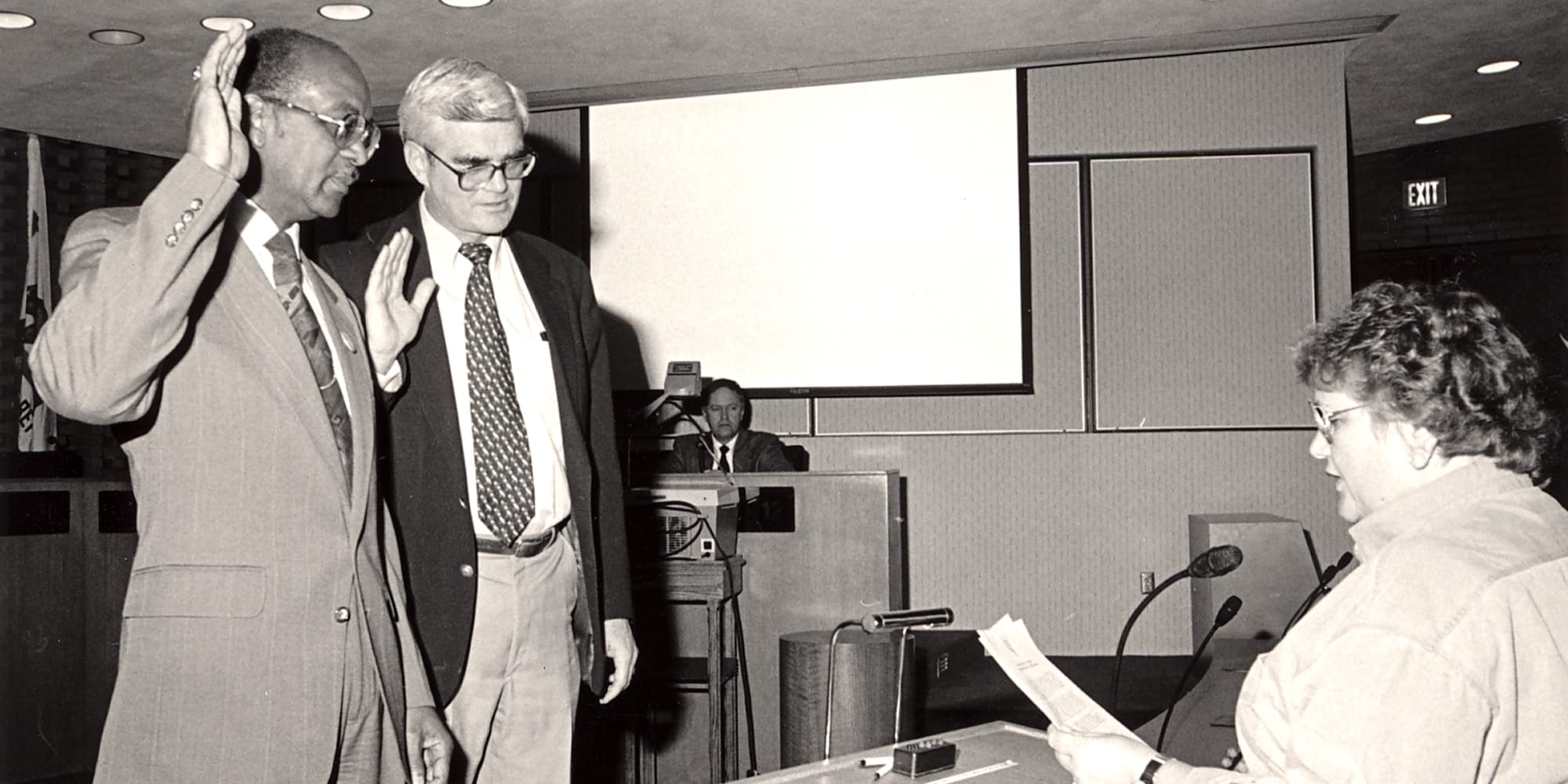

Loveridge won and held Riverside’s Ward 1 seat for three four-year terms until 1993, when he won a citywide election to become mayor. A fixture of the seventh floor of City Hall, Loveridge was re-elected mayor another four times before stepping down in 2012 to head UCR’s Inland Center for Sustainable Development and continue his work as a professor. He never lost an election.

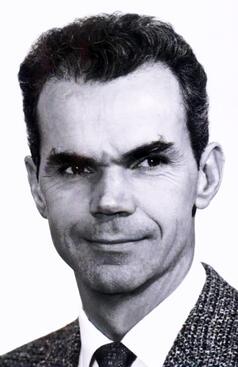

(Courtesy of Ron Loveridge)

As a city official, Loveridge strove to bring together people with diverse backgrounds but common goals to solve problems through civil deliberations. No community, he said, is better than the collective force of its neighborhoods. So, he worked to uplift neighborhoods by increasing pride, identity, and security through the creation of neighborhood councils and crime watch groups. A decades-long effort to revitalize downtown Riverside began with the creation of the Riverside Downtown Association, a coalition of business owners, downtown workers, property owners, and city representatives, among other stakeholders.

A pivotable success was the reopening of the historic Mission Inn in 1993, which is now a downtown anchor of culture, commerce, tourism, and the venue for the annual Festival of Lights, attracting thousands during the holiday season. The hotel had been closed for eight years prior, surrounded by a chain-link fence, and, before then, was plagued by decades of mismanagement under both private and city ownership.

It would be one of several downtown successes. When a bank abandoned what is now the California Tower building, the city acquired the property and leased it to the state, bringing in several commercial businesses and eateries serving more than a hundred state employees, among others. The city also successfully marketed a portion of downtown as a judicial center, which involved Riverside County renovating and building new superior and family court facilities; the state building a division of the 4th District Court of Appeal; and the federal government building district and bankruptcy courthouses. These and other improvements helped Riverside win a coveted All-America City award in 1998.

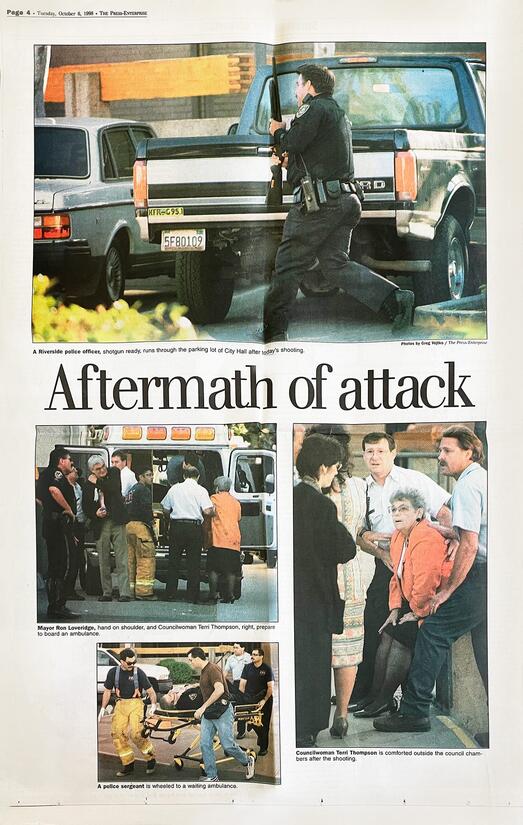

Loveridge’s political career, however, then took a violent turn. In early October of 1998, as revitalization efforts were underway, a former city parks worker walked into a morning Redevelopment Agency meeting at City Hall and opened fire with a 9-millimeter handgun.

“There’s no rational reason why I should still be alive. He was 10 feet away,” Loveridge said. “I just happened to be turning around to get coffee.”

A bullet grazed Loveridge’s back and shoulder, ripping a gash that required 16 stitches. After he left a hospital emergency room, he returned to City Hall that day and joined then-Police Chief Jerry Carroll for a press conference, during which Loveridge lauded the bravery of the responding police officers and expressed concerns for the more seriously wounded, including Councilmember Chuck Beaty. Beaty was left in critical condition with wounds to his face and chest and would endure a long recovery. But Loveridge quickly put the shooting behind him.

“There’s no rational reason why I should still be alive. He was 10 feet away.”

“You had to see it as an anomaly,” he said. “If you thought that at any time somebody’s going to leap out of the bushes and take the shot, you couldn’t function.”

Less than three months later, Loveridge faced the greatest crisis of his political tenure. Four police officers shot and killed Tyisha Miller, a 19-year-old Black woman from Rubidoux who had been unconscious with a handgun on her lap while parked at a gas station near the Riverside Plaza. Members of her family had called authorities seeking medical attention for her. Police said she appeared to reach for the gun when they broke the glass of the car window to get her out of the vehicle. The officers fired 23 shots, hitting her 12 times.

Repeated protests erupted in the coming months, with the city accused of systematic racism in the police department. The Revs. Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton and comedian Dick Gregory were among the activists that joined the protests and spoke at Riverside churches and other venues. Miller’s family retained celebrity attorney Johnnie Cochran, then famous for his successful defense of football legend O.J. Simpson in a double murder case.

Investigations found incidents of racism, including racist statements made by officers at the Miller shooting scene. State Attorney General Bill Lockyer imposed a five-year consent decree on the city, a kind of legal settlement in which the city and the state agreed on a series of reforms in the police department. Loveridge described the consent decree as an important, positive step. In the wake of the shooting controversy, the city recruited Russ Leach from El Paso to be the new police chief. The consent decree gave Leach the additional authority he needed to break through what Lockyer described as a “cowboy culture” in the police department.

“The consent decree allowed Russ Leach to change and professionalize the police department,” Loveridge said, noting Leach succeeded in shifting the dynamic between the chief and the police union.

Riverside officers underwent use-of-force training and the department added less lethal weapons to their arsenal. The city also increased the ratio of supervisors per officer and required more experienced officers to work the graveyard shift. But most significantly, the city added a layer of police accountability by forming a Community Police Review Commission appointed by City Council. Armed with subpoena power, the commission now reviews all fatal encounters with Riverside police and investigates citizen complaints.

Beyond Riverside, Loveridge worked for decades to clean up Southern California’s severe air pollution, which made people ill and shortened lives. When arriving in Riverside in 1965, he was struck by the debilitating layer of smog that regularly blanketed the city, sometimes making it impossible to see Box Springs Mountain from UCR less than a mile away.

“Coming to Riverside, we hit the Cajon Pass, and I was dumfounded by what I saw,” he said. “I couldn’t believe people took it. So much of my advocacy from that day on has been to do something about the air.”

Loveridge regularly consulted with UCR professor John T. Middleton, a pioneering air pollution scientist, who in 1962 established the Statewide Air Pollution Research Center on the UCR campus and went on to be the first director of the precursor to the California Air Resources Board and, later, the director of what became the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Loveridge got involved locally in the 1970s by serving on a city Environmental Protection Commission and joining a citizens’ advisory panel of the South Coast Air Quality Management District, or AQMD, which regulates smokestacks and other nonmoving sources of air pollution.

“It is a world-class success story. The air is cleaner because of public policy.”

He became a regional and statewide force for improving air quality when he joined the AQMD policymaking board in 1995. Starting in 2004, he became the AQMD’s representative on the California Air Resources Board, which regulates car and truck emissions, Southern California’s greatest source of air pollution. Slowly but surely, pollution levels dropped as the two agencies cracked down on pollution sources and toughened air quality standards.

“It is a world-class success story,” said Loveridge, who served on both boards until he stepped down as mayor. “The air is cleaner because of public policy. What the AQMD was dealing with was not aesthetics. It was dealing with life and death because health became the primary framework.”

After leaving public office, Loveridge become director of UCR’s Inland Center for Sustainable Development, a research hub operated by the School of Public Policy. He held this position for five years and remains a senior advisor. He now holds leadership positions with groups overseeing or advocating for the Coalition for Clean Air, California Citrus State Historic Park, Civil Rights Institute of Inland Southern California, Raincross Group, Ontario International Airport, Inland Economic Growth & Opportunity, and Riverside’s International Relations Council.

Even now, Loveridge still hikes daily to the top of Mount Rubidoux and relishes his continuing work as a political science professor, teaching a class about local leadership in California, conducting seminars, and placing interns.

“One of the exciting things about being a professor here is teaching a class of 20 to 30 people,” he said. “You get to know them. You talk to them, and you listen to them. It feels good because they’re curious about what you teach, and you value the exchanges with students.”

The Ronald Loveridge Tribute Fund

Ron Loveridge, political science professor and former mayor, has inspired UCR students for decades with an emphasis on learning outside of the classroom through fieldwork and internships. In imagining a future beyond his involvement, the Ronald Loveridge Tribute Fund ensures a permanent endowment to provide students with lifetime career opportunities and sustain the management of Loveridge programs.

Make your gift to the Ronald Loveridge Tribute Fund at donate.ucr.edu/ronloveridge.