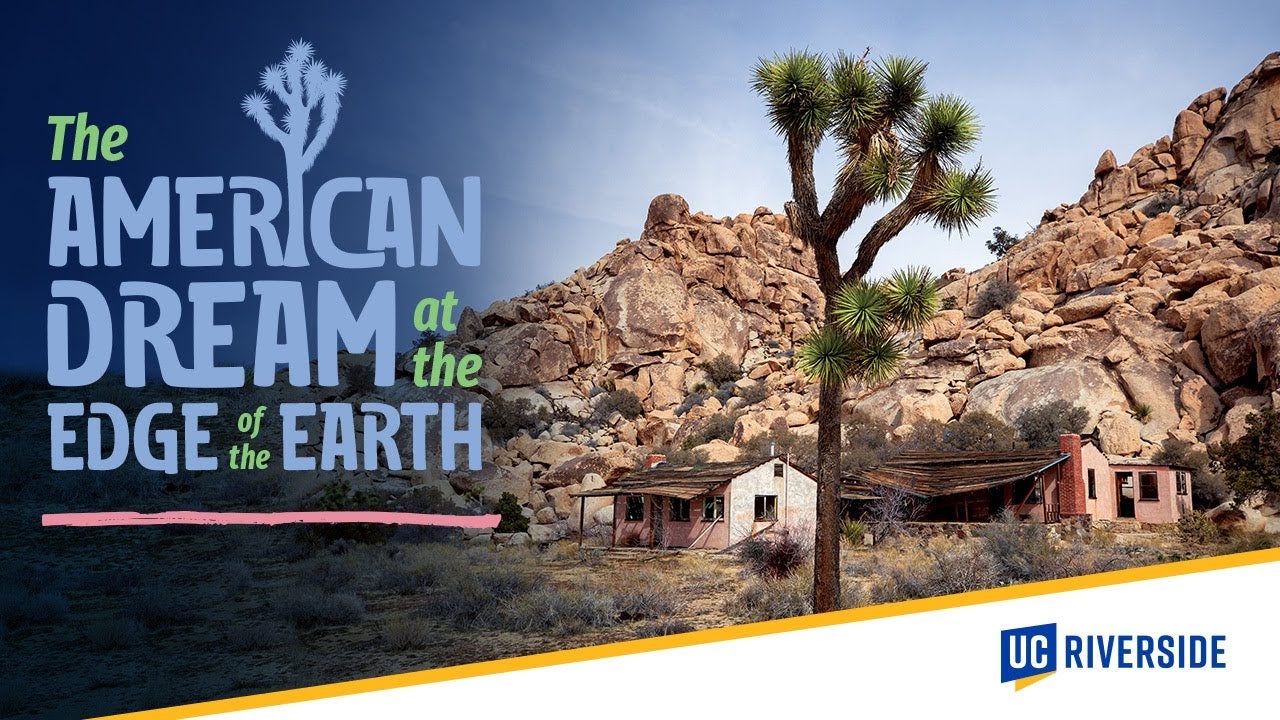

The American Dream at the Edge of the Earth

A comprehensive survey of private land ownership in Joshua Tree National Park by three UCR historians shines light on the invisible spaces and stories that lie beyond the park’s main drag

By Tess Eyrich | Photos by Stan Lim

A t nearly 800,000 acres, Joshua Tree National Park could comfortably house the entire state of Rhode Island atop its sun-bleached terrain. Here, under skies that boast world-class stargazing once the sun sets, prehistoric-looking Joshua trees mingle with elephant-sized boulders that seem designed to convince you that yes, in fact, you very well might be on the surface of the moon. The desert has never been known for its hospitality to living things, yet Joshua Tree manages to net a respectable 3 million visitors each year. As about 85% of the park comprises roadless wilderness, however, most of those visitors will never encounter its vast backcountry. Nor will they come to truly comprehend the “untamed” nature of the park, said Catherine Gudis, an associate professor of history and the director of UCR’s public history program.

Gudis is one of three UCR researchers with outsize knowledge of what lies beyond Joshua Tree’s main thoroughfare, the aptly named Park Boulevard. Among what goes unseen by the average day-tripper or weekend warrior: a patchwork of about 100 private land holdings, known as inholdings, that exist within the park’s boundaries — some of which have remained owned by the same families across multiple generations.

In 2016, Gudis joined David Biggs, a professor of history at UCR, and Todd Luce, then a doctoral student in the public history program, in launching a Historic Resource Study, or HRS, of Joshua Tree at the behest of the National Park Service. Produced periodically at national parks around the country, these studies provide historical overviews of federal lands and are used to identify and chronicle the legacies of their above-ground cultural resources. What’s written in an HRS can influence a variety of outcomes, Biggs said, such as the decision to add a structure located within a park to the National Register of Historic Places, or NRHP, for future preservation and potential restoration. In turn, such studies can affect how interpretation and education are conducted by park staffers to enhance how visitors experience and make meaning of their time inside a park.

The nearly 300-page report produced by Biggs, Gudis, and Luce, “Homesteads in Joshua Tree National Park,” surveys Joshua Tree’s homesteads and inholdings, with a focus on the roughly 160-year period of recorded private land ownership spanning from the mid-1800s to the present. Their expansive study explores the region’s early settlement by miners and ranchers, its evolution into a haven for down-on-their-luck Angelenos seeking refuge from city life amid the Great Depression, its designation as a national monument in 1936, and its rebirth as a leisure destination and site of spiritual awakening for members of midcentury countercultural movements.

Welcome to Joshua Tree

By now you might be wondering how, exactly, it’s possible to privately own land within a national park. That’s where timing comes into play.

“When a national park is formed, it’s formed over a patchwork of other properties,” Biggs explained. “The park doesn’t have the right to claim eminent domain, so people with private properties get sort of surrounded by the boundaries of a new park or monument. When they want to transfer their property, the park doesn’t get first rights to buy it, so the owners can choose to pass it on to their heirs or sell it to other private buyers.”

What results is an unusual mosaic of private-mixed-with-public land, especially in national parks in the West, Biggs said, as most of the Western parks were established fairly late, with the primary exceptions of Yellowstone in 1872 and Yosemite in 1890. Joshua Tree, in fact, graduated from a national monument to a national park only in 1994.

“When a national park is formed, it’s formed over a patchwork of other properties.”

— David Biggs

The relative youth of many Western parks makes it common for them to include some privately owned property, Luce said. For Luce, an Inland Southern California native and Riverside resident since 1995, scoring the contract with the National Park Service also meant a first-ever visit to Joshua Tree in September 2016. At the time, Luce was knee-deep in another project of similar scope — writing his doctoral dissertation, which he would later term an “eco-biography” of the Salton Sea.

Collaborating closely with Biggs and Gudis, Luce began to work his way through the existing inventory of properties and structures in Joshua Tree provided to the team by park leadership. Frequently, he said, he would start with just the last name of a property owner, working backward to unravel the mystery of the person behind the name. Aiding him in the process was an arsenal of tools, some web-based — ancestry.com, UCR’s California Digital Newspaper Collection, newspapers.com — and some involving good old-fashioned gumshoe detective work, like visiting physical archives, county offices for tax records, or UCR’s Orbach Library to scan aerial photographs for a bird’s-eye view of the park in the 1950s. Working on a more technical project than usual turned out to be a boon, the researchers said, as it provided a longer timeline with space to revisit the park and conduct “contemporary archaeological surveys” of the properties themselves.

“You might be looking at plumbing, or a concrete foundation, or evidence that something burned down, then raising the question to someone who works for the park: ‘Did you know this house burned down?’” Biggs said.

The stories the researchers were able to craft about real people using Luce’s genealogical research add new contextual depth to how visitors might experience the park, said Gudis, who also worked with Luce to conduct a set of oral history interviews for the project. She described part of her role as “to help push to the forefront the elements that were significant in those stories” and connect them to broader social contexts.

“It’s really difficult to write about common folk,” Luce admitted. “We leave behind numbers — census data, tax data — and I used a lot of those things to get started. That’s the skeleton, but putting flesh on the skeleton can be really tough. There’s a fair amount of structured speculation that takes place in the report because there’s only so much we can know at this point; those voices no longer exist.”

Explore the former homesteads and history of Joshua Tree National Park with UCR researchers Catherine Gudis, David Biggs, and Todd Luce.

Based on what we do know, the researchers pin the origin of private land ownership in the park largely to federal policies that encouraged Western settlement — and by extension, Native removal. The first such policy, the Homestead Act of 1862, granted ownership of 160-acre plots of “free” public land to eligible recipients who had committed to cultivating the land for at least five years. To be considered eligible under the act, recipients also had to be eligible for U.S. citizenship at the time, a restriction that effectively excluded Asian immigrants and Native Americans from participation

“Homesteading was part of a longer process of settler colonialism in the West,” Gudis said, noting the Cahuilla, Chemehuevi, and Serrano peoples were systematically pushed onto reservations in the region.

For the early homesteaders, successfully growing crops proved difficult, and many relied instead on beekeeping, poultry raising, and goat herding to meet the act’s requirements. Later, the General Mining Act of 1872 provided additional avenues for extraction of Joshua Tree’s natural resources by legitimizing the mining and milling of ore.

The Pacific Railway Act had perhaps the strongest impact on land ownership in the region. The act incentivized westward railroad expansion by rewarding railroad companies with tracts of public land in exchange for miles of track laid. As the researchers note in their report, by the early 1880s, the act had resulted in Southern Pacific Railroad becoming the largest private landowner both in what would become Joshua Tree National Park and California at large. The company continued to broker sales of its parcels to private owners even after Joshua Tree’s designation as a national monument in 1936.

the late 1920s to mid-1930s.

Tree Houses

Today, most of the inholdings with intact historical structures reside in two of the park’s six subareas: Lost Horse Valley, which contains the six sites within the park that have already been added to the NRHP, and the bordering Quail Springs. Those familiar with Joshua Tree’s history may already know William “Bill” Keys as central to the park’s lore. A miner whose namesake ranch remains open to the public, Keys met his match in his wife, Frances Mae Lawton, whose varied work on the ranch included butchering meat and canning produce, educating their and other local children in an on-property schoolhouse, and serving as the family doctor. To supplement the family’s income, Frances made and sold bonnets to a growing clientele of local women.

“One thing I really enjoyed about this project was learning about all these women who were just out there doing it, handling business and subverting the traditional frontier-pioneer narrative of rugged individualism centered around masculinity,” Luce said.

Women would continue to make their mark on the Joshua Tree landscape well into the 20th century, including during the Great Depression, when homesteading in Joshua Tree became an increasingly viable option for city folk searching for a more affordable way to eke out a living. Many of these Depression-era homesteaders had landed in Los Angeles from the Midwest in the 1920s, according to the researchers, only to fall on hard times in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash. Aided by the mass production of the automobile, some, like Sherman Randolph, even became weekenders, commuting back and forth between working-class neighborhoods in Los Angeles and the desert.

“It’s really difficult to write about common folk. We leave behind numbers — census data, tax data — and I used a lot of those things to get started. That’s the skeleton, but putting flesh on the skeleton can be really tough.”

— Todd Luce

Sherman and his brother, Verne, along with Sherman’s wife, Katherine, began homesteading in Joshua Tree in the 1930s. Katherine formed a close community with other Lost Horse Valley and Quail Springs families, including the Keys family, and raised the couple’s three children alongside chickens and goats. Meanwhile, Sherman spent weekdays in Los Angeles, where he worked in a hardware store, and returned to the homestead on weekends. The brothers’ neighboring Joshua Tree homes, built from sturdy timber and bearing stone facades, remain intact and owned by their descendants. In their report, Biggs, Gudis, and Luce describe the properties as eligible for nomination to the NRHP due to their historical significance and association with Depression-era homesteading.

“When we started this project, one of the things our park contacts shared with us is that they often don’t know which structures within the park to tear down because they don’t know if they’re architecturally or historically significant,” Biggs said. “So, one of the roles that this report plays is to help intercede before the bulldozers show up — to say, ‘Wait! That’s historically significant, and you should keep it or try to buy it.’”

Other homes, like that of Signe and Charles Ohlson, exist today only as ruins. The Ohlson home was built on a property once owned by the disgraced ex-sheriff Worth Bagley, whose tenure in Joshua Tree lasted just five years and ended dramatically when, in 1943, he was shot and killed by none other than Bill Keys, whom Bagley accused of trespassing. Keys served five years in San Quentin State Prison for the murder, returning to his Joshua Tree ranch upon release; meanwhile, newcomer Signe befriended Frances while her husband was incarcerated. After Signe and Charles divorced in 1948, she became the sole owner of the property they had named “Wonderland Ranch” and opened a health foods store in nearby Twentynine Palms.

A New Day Dawns

Following World War II, Joshua Tree evolved into a new sort of destination for a new sort of American dream. Amid the postwar economic boom, families like the Cases sought to purchase vacation homes that could be used for leisure and recreation. Some were unlucky, purchasing lots in failed subdivisions that never materialized. Others purchased existing properties from private owners who were moving on — a technique employed in 1968 by Harry Cohn Jr., whose storied Cohn Ranch endures.

Tourism in Joshua Tree had begun to blossom with the site’s establishment as a national monument. But it wasn’t until the late 1940s and ’50s that people began to visit Joshua Tree for spiritual rejuvenation and to shed the repressive cloak of suburbanized America, the researchers noted. In the 1960s, actors like Ted Markland, John Drew Barrymore, and Dennis Hopper flocked to the desert, where they practiced a distinctly Californian blend of mysticism that melded Eastern and Native American “ways of knowing.” Cohn Jr.’s father, Harry Cohn Sr., had co-founded Columbia Pictures, which put Cohn Jr. in close proximity with members of Hollywood’s film and music elite. His relationship with Markland introduced him to Joshua Tree, where he purchased a property and promptly added a Navajo-style hogan, or sweat lodge, to its grounds; the hogan still stands today.

“This is all part of the individualism of the American way ... it’s about being allowed to do whatever you want with your land, no matter the fact that you’re in the middle of a public, federally owned national park.”

— Catherine Gudis

Over the years, guests including Peter Fonda, Steve McQueen, Alan Ginsberg, Keith Richards, Donovan, Gram Parsons, and Timothy Leary would visit the property; in fact, Leary celebrated his third wedding at Cohn Ranch in 1967. After Cohn Jr. died in 1989, his wife Joyce installed metal enclosures on the property to house her collection of wild cats, welcoming a menagerie of ocelots, leopards, lynxes, and tigers to Joshua Tree. Though a large portion of the property was transferred to the Mojave Desert Land Trust upon her death in 2005, the ranch’s main structures remain owned by the Cohn family.

“What we learned from properties like Cohn Ranch and what locals call the ‘Whiskey Bottle House’ in Pinto Basin is that there is no one cookie-cutter idea of ‘counterculture,’” Gudis said. “This concept of the gun-toting hippie emerges. It’s not all a particular, vegan, peaceful, at-one-with-nature idea. In fact, it includes following these really independent practices — having an exotic animal compound, building a sweat lodge, doing shooting practice in your backyard. This is all part of the individualism of the American way, and it doesn’t fit with just one political perspective either. It’s about being allowed to do whatever you want with your land, no matter the fact that you’re in the middle of a public, federally owned national park.”

Today, the droopy-hatted hipsters for whom Joshua Tree serves as a playground could look to the Cohn Ranch crew as spiritual ancestors of sorts. They come to Joshua Tree to buy quartz crystals and take sound baths. They book healing retreats and sit for ayahuasca ceremonies. They want to be transformed by the desert, to forge a deeper, more authentic connection with the earth, but the reality is the desert is unyielding. Resources are scarce, and everyone has to go home eventually. What gets left behind, however, might someday tell the historians of the future stories about what human activity and land use in Joshua Tree looked like in the 2020s — about who we were and what we cared about.

“There is one property inside the park that sold a few years ago for $625,000,” Luce said of the property identified in the researchers’ report as once belonging to the Gainder family. “It originally had this little adobe that was built in the ’50s and was passed on through a series of owners. When I went up to see it after its most recent purchase, there was all this new building happening — really nice stuff. I don’t know what the idea behind that is, but if I had to guess, I’d imagine it’s to create some sort of luxury Airbnb thing, like an exclusive way to stay inside the park.”

Someday soon, Luce imagines, visitors might even be able to book a tour inspired by the stories and people enshrined in the Historic Resource Study. The dream of the desert could go on forever — if we could only keep the sun out of our eyes for a little while longer.