Baby Shark, Huge Splash

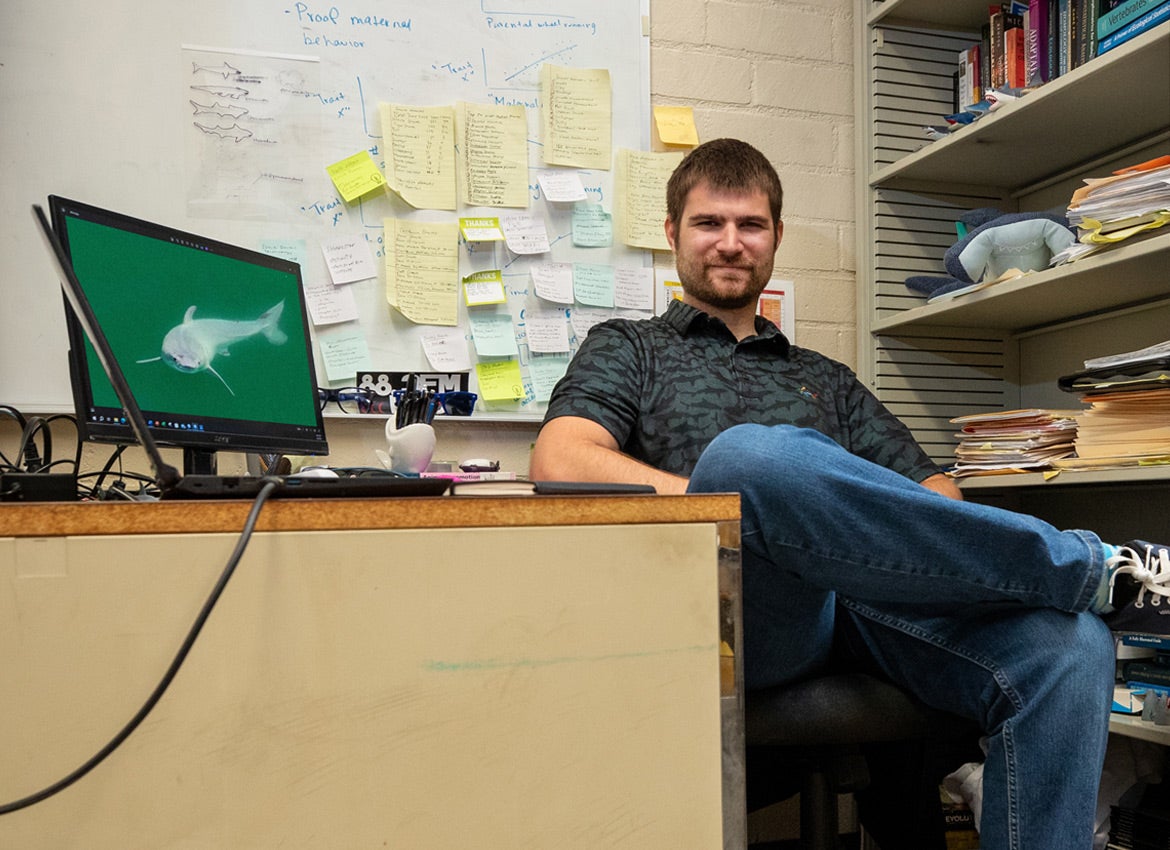

UCR doctoral student Phillip Sternes on being the first to spot a newborn great white, why it made waves across the world, and the dangers to sharks lurking beneath the surface

By Jules Bernstein

G reat white sharks are tough to imagine as pups, both because they’re ferocious predators and because no one has ever seen one in the wild — until now. UC Riverside biology doctoral student Phillip Sternes and friend Carlos Gauna caught the world’s attention this past summer when they announced they had found a newborn great white.

Sternes and Guana, a wildlife filmmaker, were scanning the waters for sharks on July 9, 2023, near Santa Barbara. That day, something exciting appeared on the viewfinder of Gauna’s drone camera. It was a shark pup unlike any the pair had ever seen.

Great whites, referred to only as white sharks by scientists, are gray on top and white on bottom. But this roughly 5-foot-long shark was pure white. As it swam, a white layer appeared to be coming off the shark’s body, which Sternes believes was evidence of “a newborn white shark shedding its embryonic layer.” Sternes and Gauna documented their observations in the journal Environmental Biology of Fishes.

Here, Sternes spoke to UCR Magazine about the fateful day they spotted the shark, the larger significance of the sighting, and more generally about his research into the world’s most fearsome fish.

Why have baby great whites been so hard to spot in the wild?

They’re marine animals that can swim far from the coastline and very deep into the water if they want to. There’s only so much depth you can see with a drone. You can tag a shark, and that gives you its general location, but that doesn’t mean you know what it’s doing.

There’s a location that’s been dubbed the “white shark cafe” — an area off the Pacific coast where we think they go to eat. But it’s hard to track migratory marine animals and follow them in their day-to-day lives. They’re elusive, and you’re already trying to thread a needle just watching their activities. Then, if you want to observe a birth, you’re looking for a very specific point in time when pups are coming out.

What led you to believe that what you saw was a newborn great white?

Prior research suggests the region from Southern California through Baja is a breeding ground, and the sighting happened in that region. My collaborator saw girthy sharks in the area behaving strangely just a day prior, suggesting the presence of a pregnant one. Later, when we saw a white shark, the fins were the first giveaway. The shape was reminiscent of a newborn. There was also the white color. White sharks use intrauterine milk to nourish the pups.

Next, we did the scaling factor. When you know how high up your drone is and its field of view, you can do calculations with pixels. When you measure the pixel length of the camera, at max the shark was 1.5 meters total length, likely even smaller. This size is consistent with what we believe about newborns.

What is the significance of the sighting?

There’s a longstanding question about where white sharks are born. We don’t know exact latitudes and longitudes, but beyond that, there’s debate about how far from the shore it happens. If what we saw was truly a newborn white shark, which we think it was, this suggests the near shore hypothesis should be supported. It means they’re born in an area closer to where humans swim.

Where they are born geographically is even harder to pinpoint than proximity to shore. Recent data supports the idea of Southern California as a breeding ground, because many young white sharks have been observed. Right now, it looks like the Santa Barbara area is a location where mothers go to give birth.

Now that we have more evidence this is a breeding ground, we can try to make it a protected area. White sharks are already protected from fishing, and you’re not allowed to keep one if you catch it. But individuals still like to break that rule. There are trophy hunters. I’ve heard anecdotes of people cutting the head off or taking the jaws out and selling them on the black market.

I notified the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and they say they know about our paper, which is great. We want to increase awareness that this may be a spot for pregnant mothers and newborns so we can further limit human interactions, both from fishermen and swimmers. It’s important that these animals do what they need to do, so we can conserve the species. You especially don’t want pregnant mothers getting caught, or pups.

“White sharks might be scary to some, but they’re very important to the marine ecosystem. We want to keep them going.”

What is the ecological importance of great white sharks?

They’re an apex predator. When they’re gone, populations of animals they used to hunt will likely increase. For example, if you do away with sharks, then sea lion populations explode. The lions prey on fish and crabs, and those populations start to drastically go down. There could be a trophic cascade where things go out of sync, resulting in a lot of dead marine animals.

The North Atlantic was a big success story. White sharks there were overfished. But then the sharks came back and the ecosystem is flourishing because the sharks are there to keep the seals in check.

In South Africa, it’s a different story. They have two major problems. One, they have the KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board, a spot where they put up nets to protect the beaches. Thirty white sharks a year were getting caught in the nets and dying. This is a problem for their population levels because they have a slow reproductive rate.

At the same time, orcas have moved closer to shore since 2015 looking for more food. We think either the warmer oceans or a decrease in their food sources are pushing them closer to shore. They’re eating white sharks that remain near shore, and we’ve seen a drastic drop in their numbers. The sea lion population is exploding, and the number of fish is dropping. If that ecosystem collapses, what happens? A dead zone. A problem, because people depend on fishing; it is critical for their economy.

White sharks might be scary to some, but they’re very important to the marine ecosystem. We want to keep them going.

What are the dangers of swimming near white sharks?

The sheer size of a pregnant white shark — it’s a huge animal, 12 feet or more. They’re capable of taking down larger-bodied prey. They might issue an investigative or defensive bite that would cause significant trauma. A newborn might actually be scared of people. But the pregnant shark would probably be defensive.

Sometimes a white shark will bite inanimate objects. We don’t know why. Is it just investigation? Is it food? If it’s something they can consume they will do so. It’s another question about white sharks. Are they super hungry? I don’t know.

How did you get interested in sharks?

I was 5 or 6 when my grandfather gave me the movie “Jaws” on VHS. It really stuck with me. Then, I went to my elementary school library and checked out “Sharks” by Gayle Gibbons. The book had a green cover and a great white illustration. I was hooked. It became a passion. I went to aquariums, watched Shark Week, all the “Jaws” movies. My parents wanted me to go to medical school, but I wasn’t in love with studies of the human body. A professor suggested I study sharks instead, and I did. I didn’t realize I could make a career out of it before that.

What are you researching at UCR?

I ask the question, “How have sharks changed in response to major changes in the Earth’s atmosphere over time?” Generally, I’m trying to help answer that question.

My dissertation is focused on the evolution of sharks’ pectoral fins. I look at their paired pectoral fins, the ones you see on their sides, which are like human arms. There is a surprising lack of knowledge about these fins despite their long evolutionary history. Sharks are one of the oldest vertebrate lineages we have, but there have been few studies on these fins’ function and how they’ve evolved.

As to how they’ve changed over time, it seems once the Earth was at its warmest temperature, something happened. This was about 93 million years ago. Some fins were short and rounded, and others responded to the change in temperature by becoming elongated like airplane wings; 747s have long wings, while fighter jets have short stubby wings and good maneuverability.

When water gets warmer, fish swim faster. That means they can go further distances. But that increases the energy cost of transportation. This is a simple physical principle. One way to improve your cost of transport is by increasing the relationship of length to width of your airplane wing, or fin.

Because of the warming we’re experiencing now, we see sharks again expanding their range. They’re swimming further. Ninety-nine percent of sharks are dependent on external temperature to maintain their metabolic processes. Some of the sharks with shorter fins, they’re swimming further north or south. Over the next thousand years or so, you’ll see a shift, and the sharks living on the bottom will get longer fins again. Today, 87% of all shark species live on or near the bottom. The ones you see on Shark Week live near the surface, but that’s not the majority of them.

“The sharks’ ability to sense what’s in the water is unparalleled. We swim near them more often than we know.”

What are sharks’ strongest senses?

They have electrophores on their snout, little black dots that can detect electrical signals in the water. They have vision, and we think shark vision is good, but mostly, I think when you drive a shark toward you, I think it’s the sound that gets them first.

Their sense of smell is good — not “they can smell a drop of blood in the water” good — but they will follow a scent. All fish have lateral lines that run along their sides. These allow them to sense pressure differences in the water. It usually equates to one-and-a-half body lengths. If you have a 10-foot shark, it can sense things 15 feet away from it. That’s how they can hunt at night.

Some researchers think white sharks have learned the differences between swimmers and sea lions. They may even have processed and passed on this knowledge. Why do we have such low numbers of attacks here on the North American West Coast? The sharks’ ability to sense what’s in the water is unparalleled. We swim near them more often than we know.

What do you want more people to know about white sharks?

Their numbers across the globe are in serious trouble. Overfishing is causing them major problems. It blows my mind they’ve survived so much, including major shifts in climate that occurred long before humans. But now there is serious extinction risk. I hope people across the world will take this into consideration.

If we start to lose them, we’ll see serious problems across the surface of the oceans. This will also translate into economic problems. Fishing areas will become dead zones — I hope people are aware of that. Sharks, as fearsome as they appear, are in major population decline. They’re in trouble.

What can people do to help?

There are a lot of nonprofits: WWF, the Save Our Seas Foundation, Beneath the Waves. A lot of groups are working to increase shark conservation laws. Donate to those groups. They support research that governments do pay attention to. Let’s get the trends reversed.