Bittersweet

Rediscovered watercolors by Elsie Lower Pomeroy depict the realities of Riverside’s orange industry and the campus’s first purpose as a citrus experiment station

By John Warren

I n a couple rooms off a lightly trafficked corner of UCR’s Department of Botany & Plant Sciences live four framed paintings that depict early citrus culture in the city of Riverside. These are not prints, nor high-end lithographs. They are original watercolors, vibrant and one-of-a-kind. The paintings won acclaim in their time but have existed in near obscurity for more than 80 years.

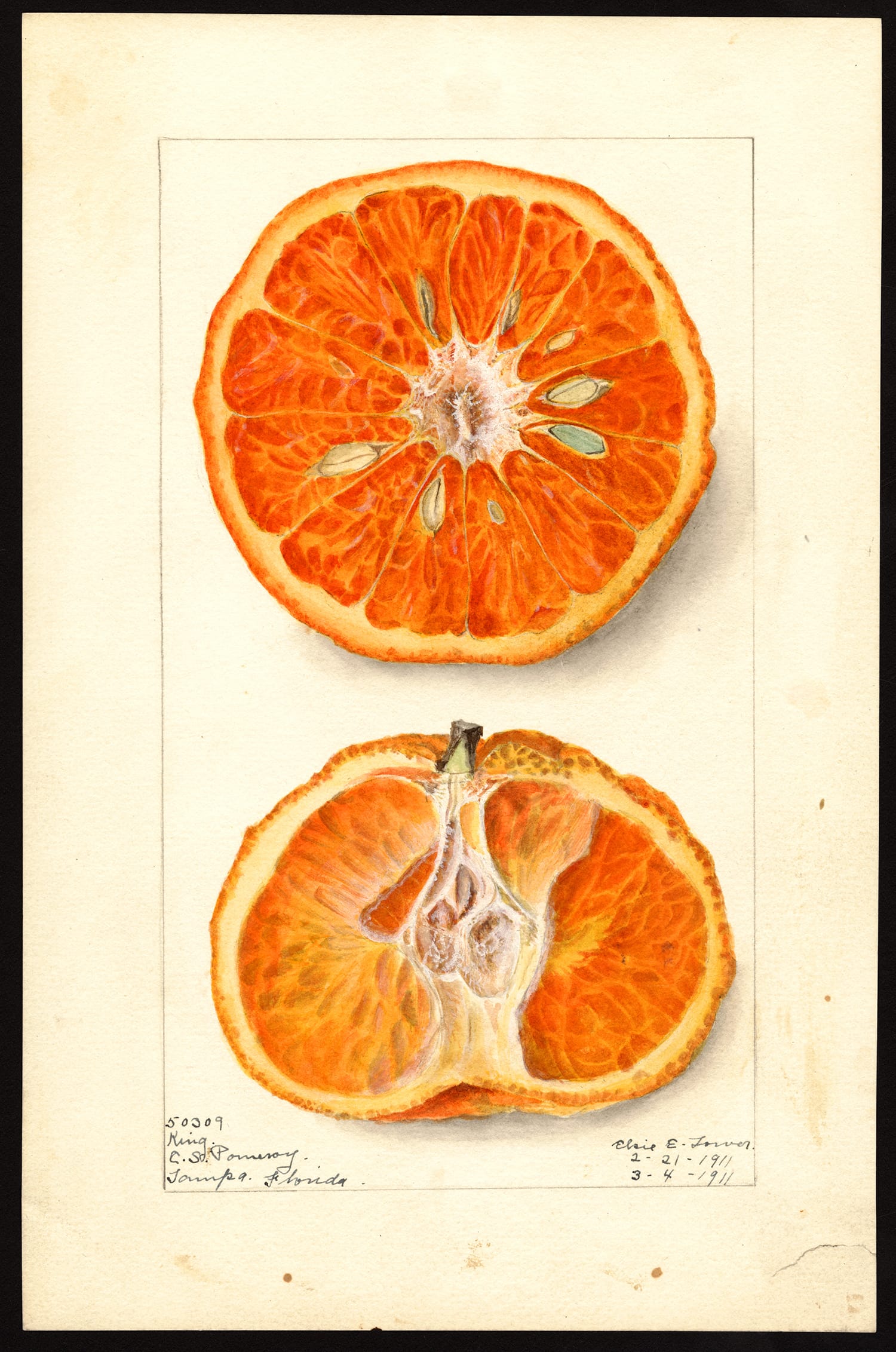

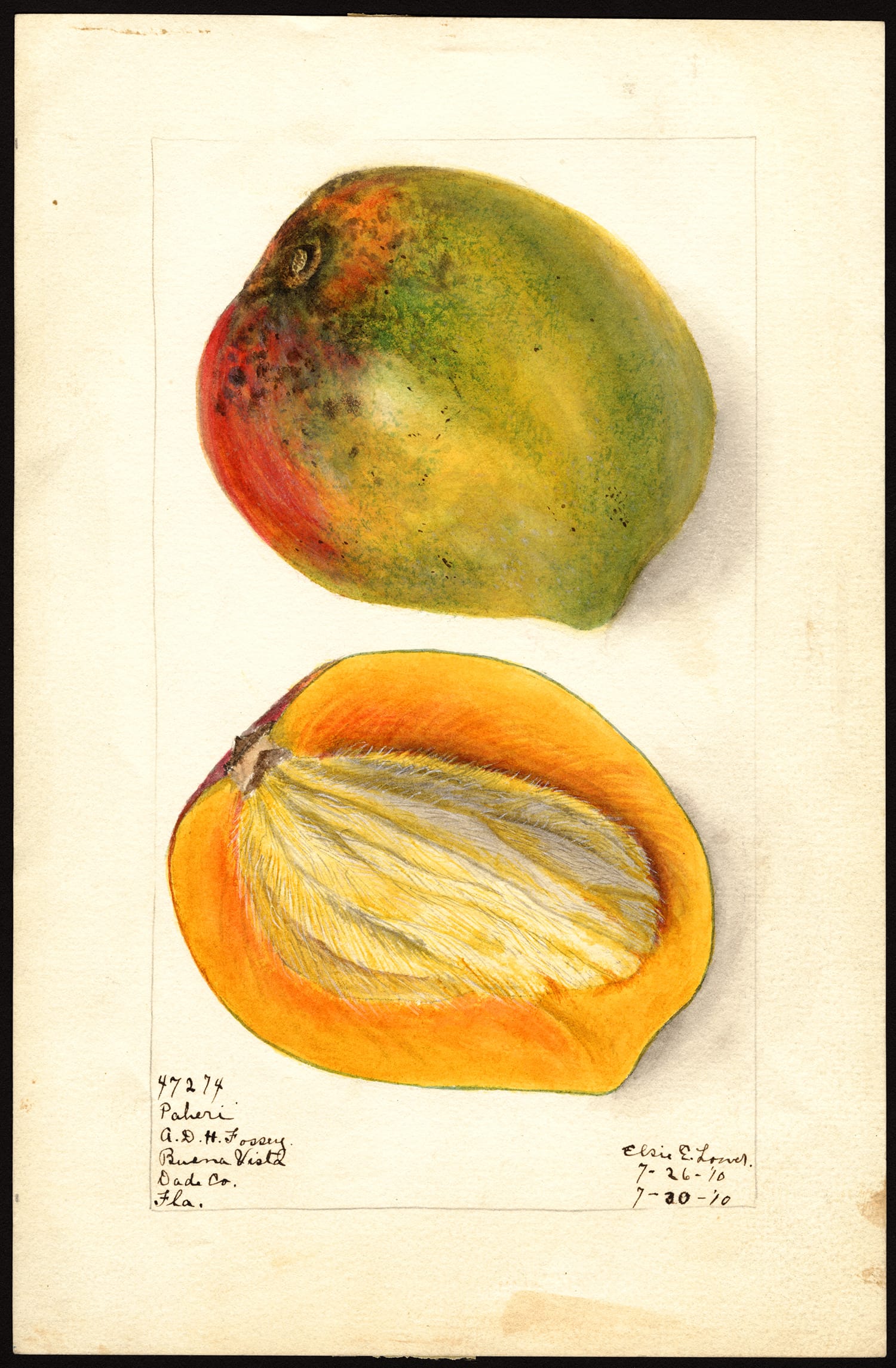

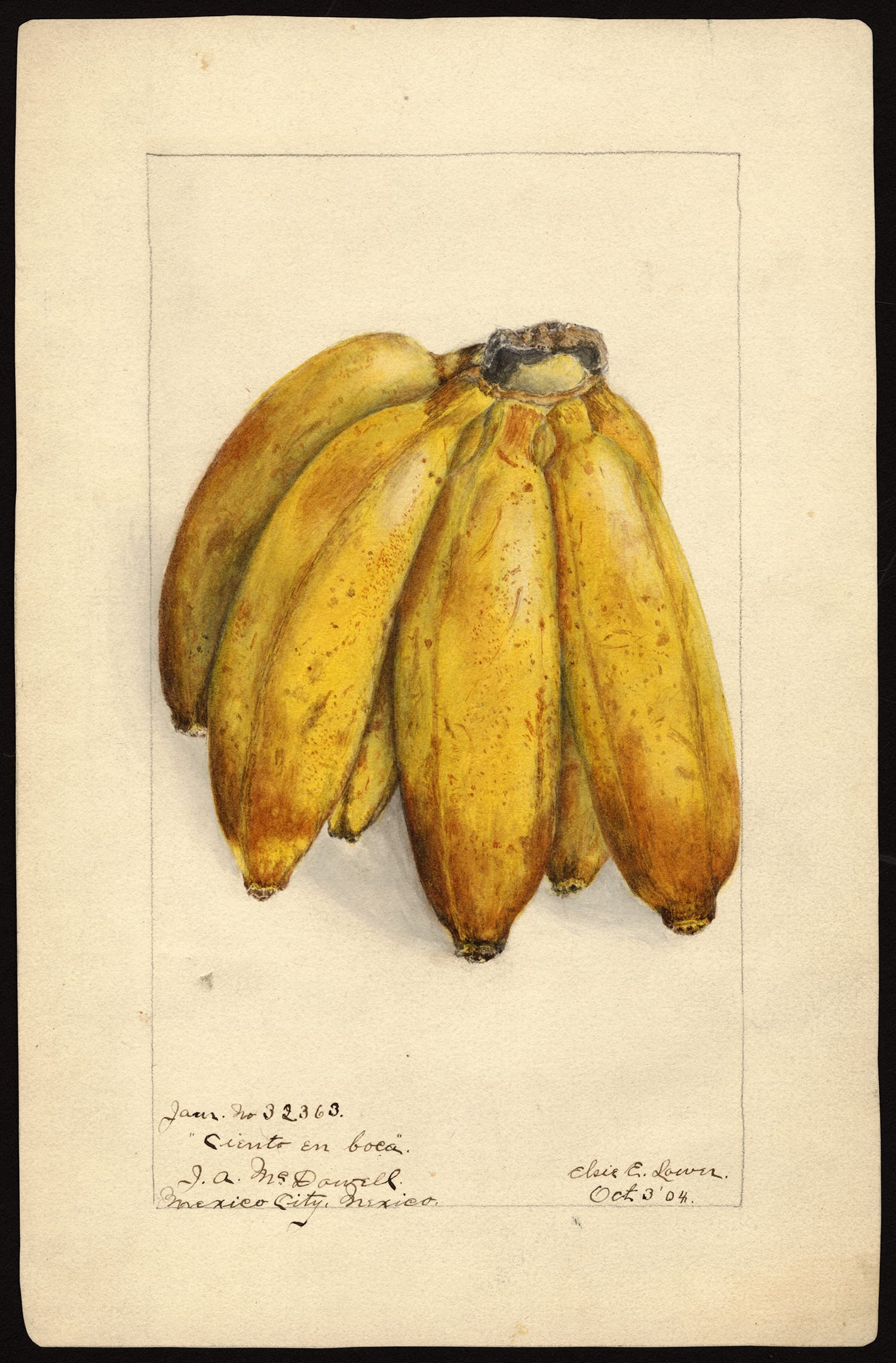

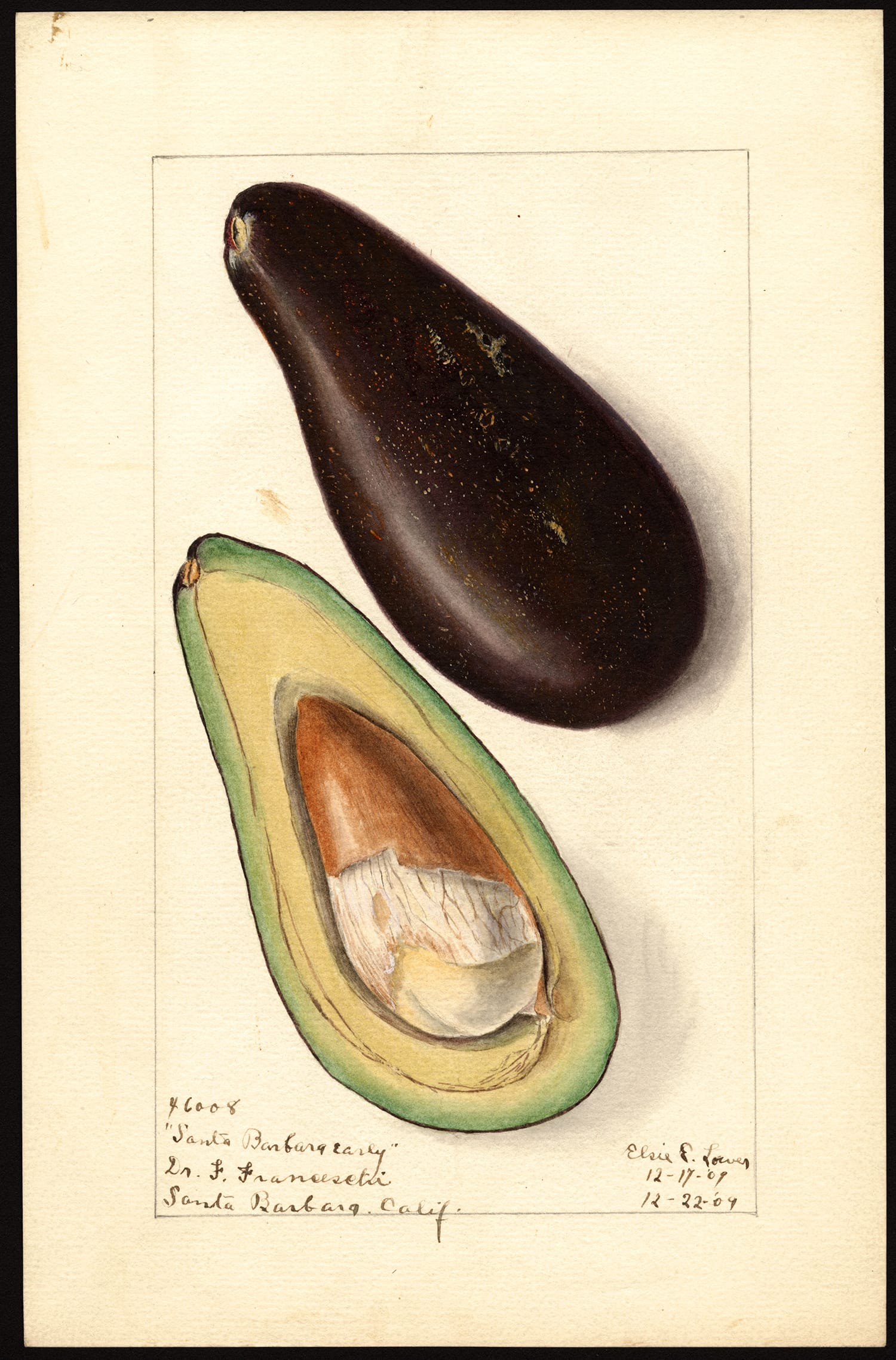

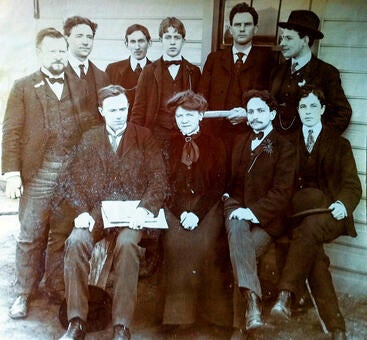

Recently, the paintings have re-emerged with the rediscovery of an artist with deep roots in agriculture and UCR’s first incarnation as the Citrus Experiment Station. The journal California History published this spring a study of American artist Elsie Lower Pomeroy (1882-1971). In her lifetime, Pomeroy was both a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) illustrator and, later, an award-winning artist associated with California Scene Painting and the 1930s California Style watercolor movement.

Pomeroy’s Legacy

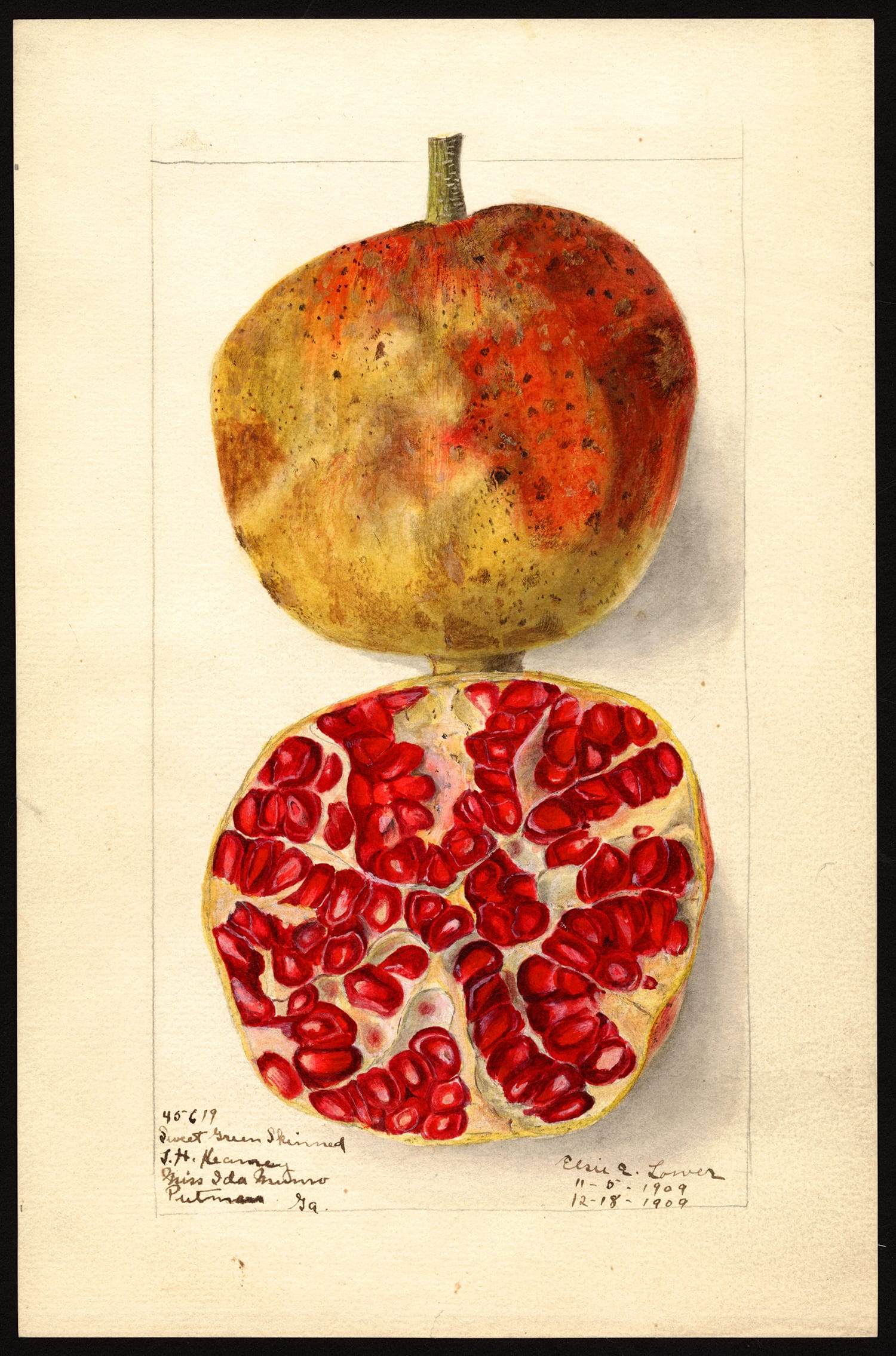

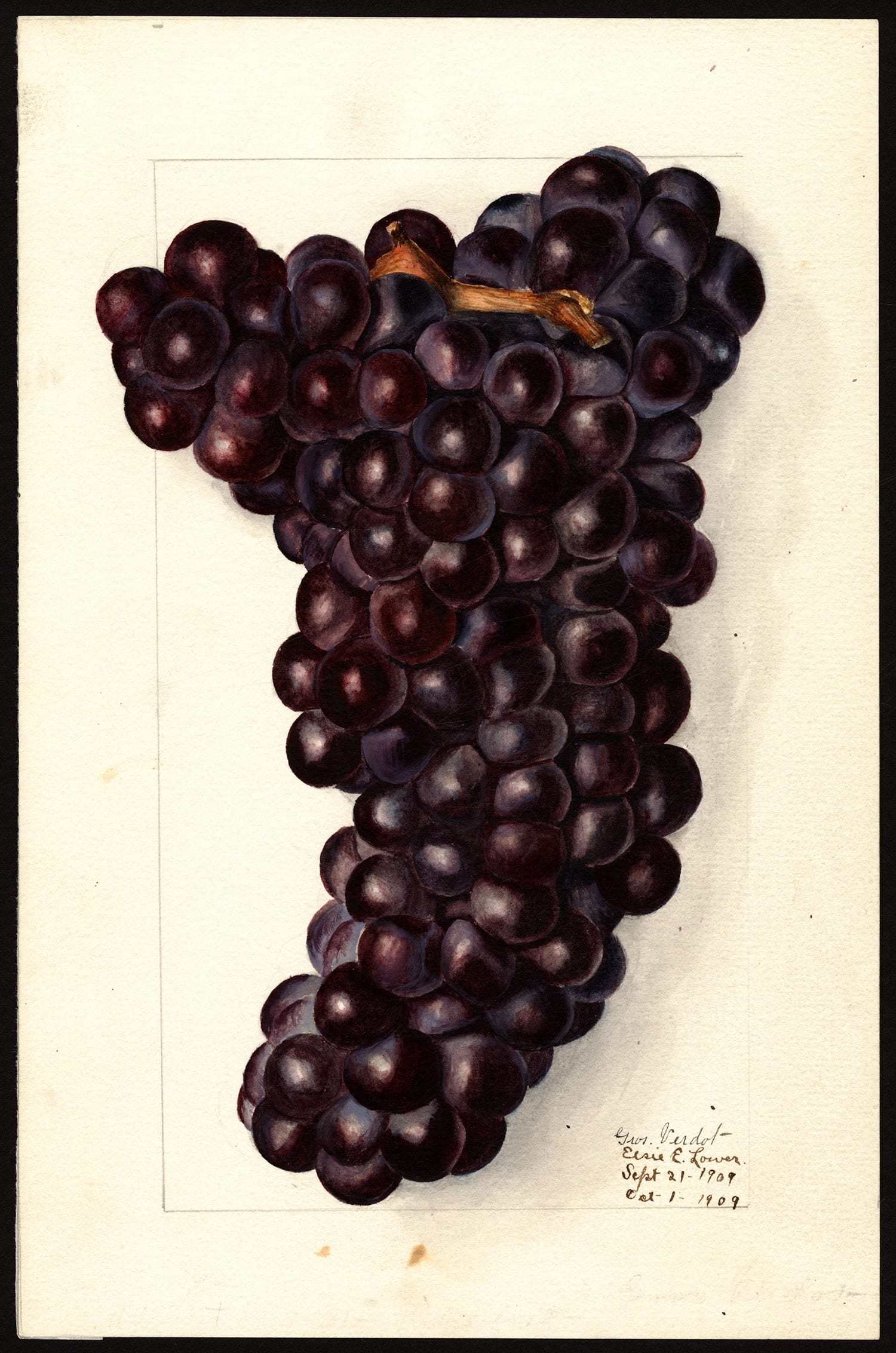

A graduate of the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design in Washington, D.C., Pomeroy began her first career as an illustrator for the USDA’s Division of Pomology when she was only 20. From 1903 to 1912, she drew hundreds of detailed paintings of fruit with photorealistic attention to detail, including about 20 watercolors of oranges, lemons, limes, and other citrus fruits. She left the USDA job in 1912 after marrying Carl Stone Pomeroy, then a USDA pomologist. The pair moved to Riverside, where Carl began work as a pomologist at the Citrus Experiment Station, the precursor to UCR.

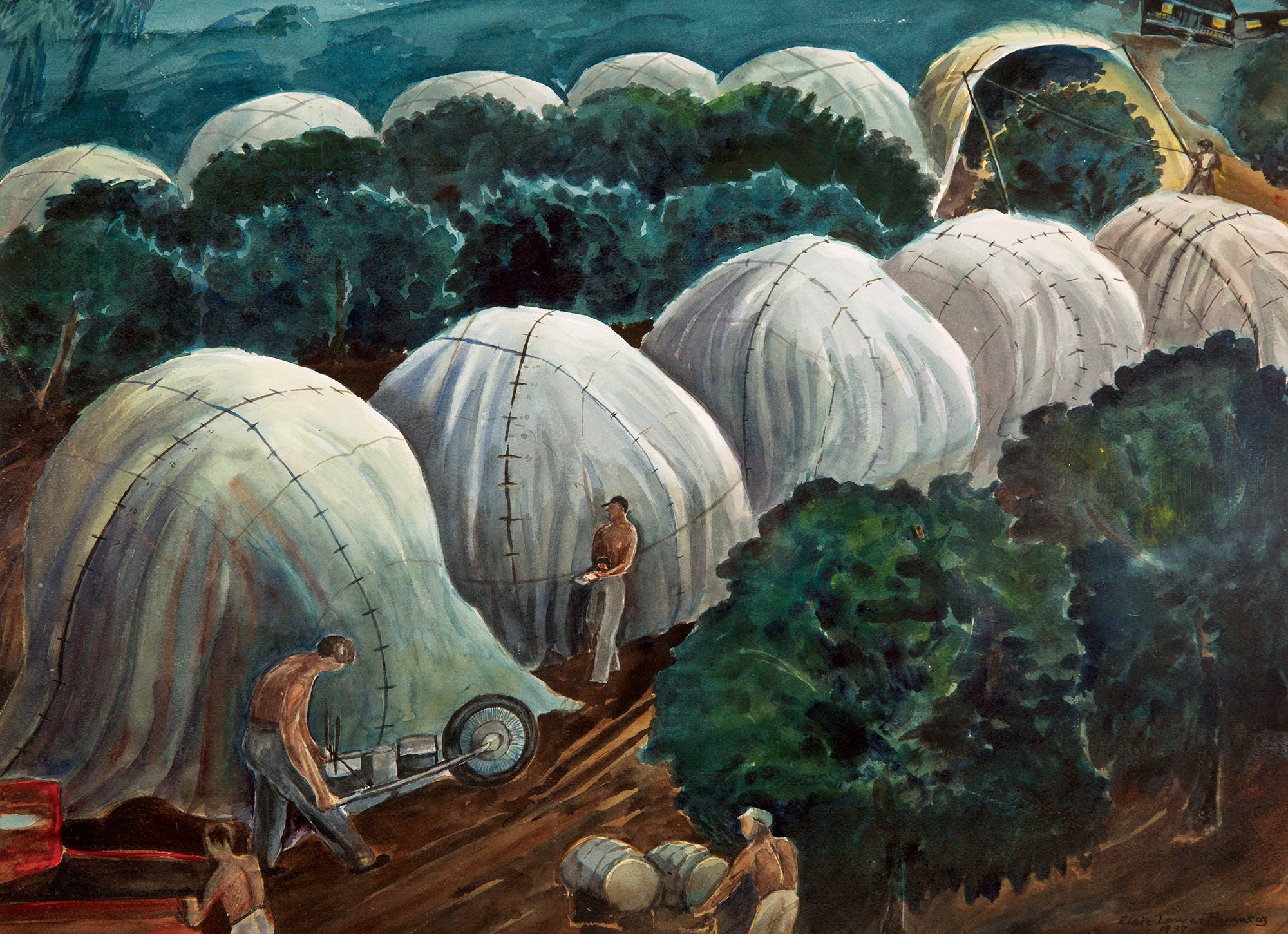

During her time living in Riverside, Pomeroy befriended and studied with Millard Sheets, a renowned artist and the leading figure in the California Style watercolor movement. She became an accomplished artist in her own right, producing work featuring California life, landscape, and agriculture. It was during this time that Pomeroy produced the series of watercolors of the Riverside region’s citrus industry, completed in 1937, that would eventually find a home at UCR.

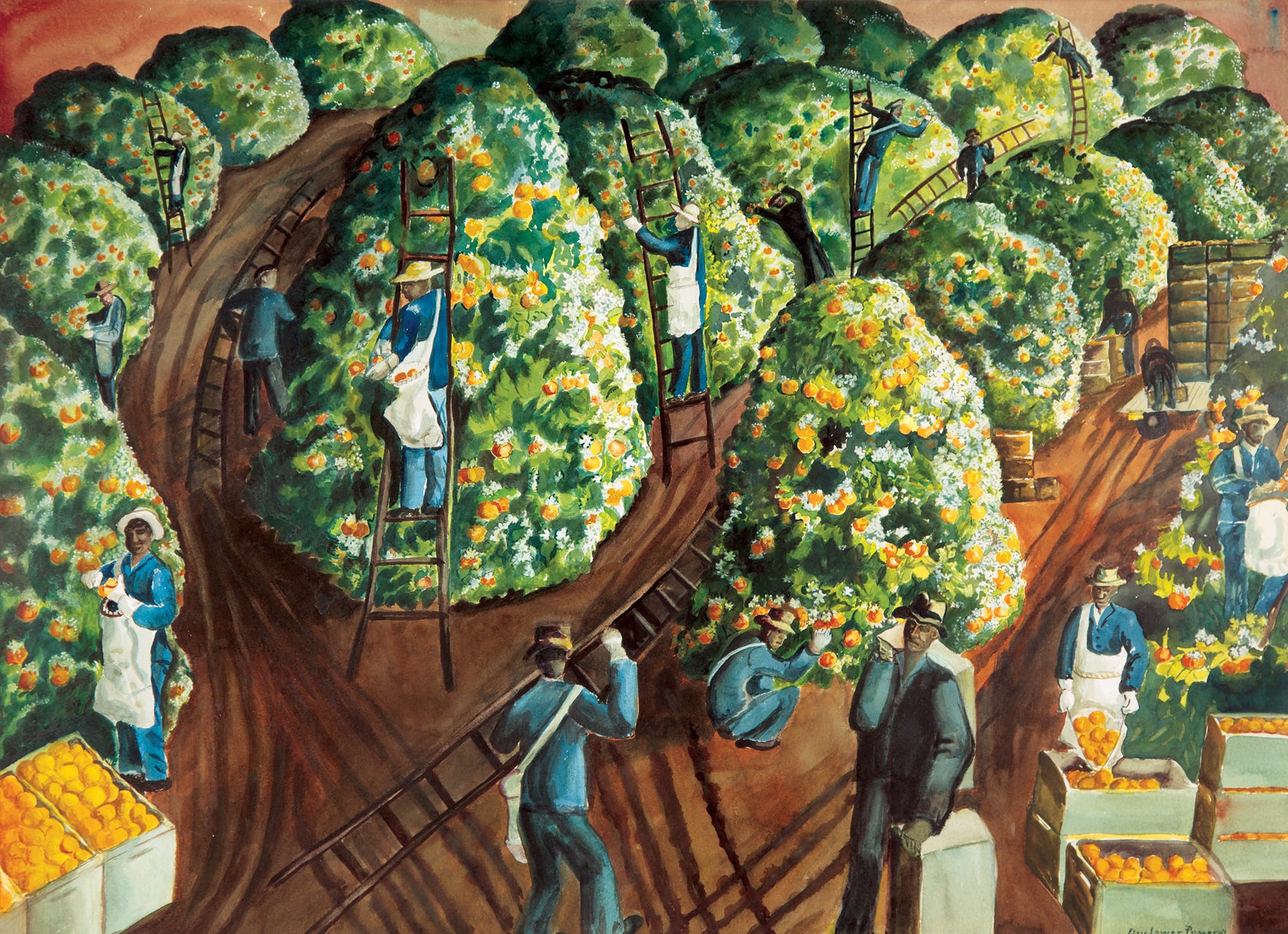

The five paintings, titled “Saving the Citrus Crop,” “Citrus Irrigation,” “Battling the Bugs,” “Orange Pickers,” and “We Grow ’Em,” depict a culture specific to Riverside and to the UCR campus’s first purpose as a citrus research center, with images of orange trees encased by fumigation tents, laborers scurrying up ladders to load fruits into crates, and “smudge pots” — oil burning devices that both fended off deadly frost and blanketed trees with soot.

The series was well known in Pomeroy’s lifetime. In 1938, she exhibited two of the watercolors at the Art Institute of Chicago’s 17th Annual International Exhibition of Water Colors, along with living artists of worldwide renown including Henri Matisse, Salvador Dali, Andrew Wyeth, Pablo Picasso, and her mentor, Sheets. In 1939, she was awarded an honorable mention at the California Water Color Society’s 19th Annual Exhibition. Arthur Millier, an artist and long-time Los Angeles Times art critic who helped establish the national reputation of the California watercolor movement, said Pomeroy was “one of the few people to ever paint a good citrus grove picture.”

Yet, as decades passed, Pomeroy and her art were largely forgotten. In recent years, Pomeroy’s great granddaughter, Stephanie Parrish, has made efforts to reclaim Pomeroy’s legacy by establishing a website and Instagram account in honor of her great grandmother. There, she’s been sharing images of Pomeroy’s art — Parrish’s family still retains roughly 250 pieces of her artwork in their personal collection — aiming to renew interest in her work and contributions to the art world.

Lost and Found

In 1962, Pomeroy’s granddaughter, then-UCR student Caryl Smith, attended an event at UCR to celebrate the university receiving the citrus series, which was donated by Pomeroy in memory of her husband. A newspaper photograph from the Marin Independent-Journal depicts Chancellor Herman Spieth and College of Agriculture Dean Alfred Boyce accepting the paintings from Smith on behalf of UCR. They hung for a time in Webber Hall, one of the campus quad’s original buildings. But they “traveled” — one was later found with a hook on the reverse side of its frame, on which a laboratory key was stored. Much like the artist herself, the paintings eventually faded into obscurity.

In 2000, for an event at the Riverside Convention Center called “A Celebration of Citrus: The Past, Present and Future,” a scavenger hunt of sorts commenced. The organizer knew of the Pomeroy paintings but wasn’t sure where to find them. Tracy Kahn, curator of UCR’s Citrus Variety Collection, in time found four of the five paintings on campus hanging in hallways of Batchelor Hall. The location of the fifth watercolor, “We Grow ’Em,” is a mystery, though Pomeroy’s family retains a version painted in oil.

For the past quarter century, Kahn has effectively been the keeper of the paintings, along with Patricia Springer, chair of the plant sciences department. The paintings, set in mid-20th-century frames with surprisingly crisp white mats and yellowing craft-paper backings, now hang in an administrative suite and a conference room in Batchelor Hall. The reverse sides of the paintings include inscriptions, presumably in Pomeroy’s hand, documenting the shows in which the paintings were exhibited and the awards they received.

During research for her upcoming book “The Aesthetics of Agriculture: Interpreting the USDA Pomological Illustrations, 1886-1942,” University of South Dakota art historian Lauren Freese was turned on to Pomeroy’s work by Parrish’s Instagram account, and her interest in the UCR-owned paintings has once again brought the series to light. In May, Freese published the California History article “The Work of Citrus: Elsie Lower Pomeroy and Southern California Citriculture” detailing Pomeroy’s career and the significance of the five watercolors.

The Riverside Citrus Paintings

Pomeroy’s work and interests as an artist had long intersected with agriculture, beginning with her time at the USDA and continuing with her husband’s work at the Citrus Experiment Station. Based first at Mount Rubidoux and then on campus at what is now Anderson Hall, the Citrus Experiment Station was established in 1907. It was an answer to pleas from the gentlemen farmers who found fortunes in the Southern California “Citrus Belt” beginning in the 1880s, after the successful cultivation of the SoCal-friendly Washington navel orange by Riversider Eliza Tibbetts. Vexed by pests and blight, the farmers campaigned for the University of California to build a citrus research station.

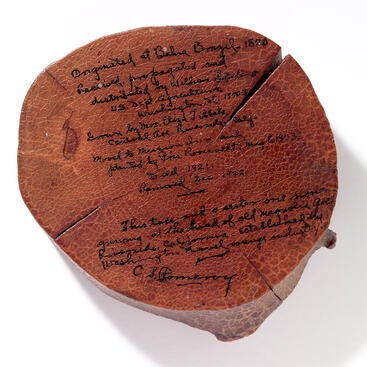

Unsurprisingly, Riverside’s citrus industry became a subject of Pomeroy’s art, including the Citrus Experiment Station and the site of the planting of one of Tibbetts two “parent” navel orange trees at the Mission Inn in downtown Riverside. Pomeroy and her husband had their own connection of sorts to Tibbetts herself — a cross-section from the trunk of Tibbetts’ tree, which remains in her family’s collection.

Pomeroy’s acute knowledge of agricultural practices and meticulous eye gained from both her time as a USDA illustrator and her exposure to Riverside’s citrus industry is evident in her five citrus paintings. In “Orange Pickers,” for instance, orange crates are stacked according to which tree they came from, as dictated by record-keeping practices of the time. The laborers are also seen carefully lowering oranges into packing crates; it was well-known that damaged skins, or peels, led to blue mold and other problems before the citrus reached market.

“In the UCR paintings, she utilized a selective attention to detail that is essential for successful pomological illustration,” Freese said. “Her substantial experience as a pomological illustrator significantly informed her work in Riverside, both in terms of style and her sensitivity to the reality of industrial citrus.”

In her article, Freese states that the five paintings “bridge art and agriculture.” Unlike other citriculture painters of the time who idealized the orange harvest, Pomeroy presents a grittier image — “an industrial reality” that included unsafe labor practices. Freese maintains that Pomeroy’s paintings “vividly convey the tensions between the romance and the reality of orange cultivation.”

“Pomeroy’s aesthetic and content choices, unlike many depictions of Southland citrus, prioritize backbreaking industrial labor over a beautiful and unproblematic citrus garden,” Freese wrote. “Pomeroy’s series contracts the dangers and pitfalls of orange farming with the economic and culinary upside, especially for the wealthy growers that profited from the labor depicted.”

The paintings, Freese wrote, reconsidered the white, male-dominated citrus industry by portraying the role of women and minoritized people. In her journal article, Freese uses the paintings as a springboard to revisit the demographic hierarchy of citriculture. For instance, the higher-paid specialists who fumigated trees were usually white; the pickers were people of color.

“These paintings depict historic activities that occurred in the 1930s,” Kahn said. “It’s important to preserve those cultural practices of that period of the citrus industry that have now changed.”

In Kahn’s research, she discovered the paintings may at one time have been formally accessioned into the collection of UCR’s Sweeney Art Gallery, part of the UCR Arts museum in downtown Riverside. But no supporting evidence has surfaced, and so they remain in the care of Kahn and Springer. Eventually, they would like the paintings better protected and maintained by an archivist, and Springer is considering having high-resolution prints made.

“In general, I believe art should be available for people to enjoy, so should be displayed, if possible,” Springer said. “These paintings are wonderful depictions of the citrus industry — they simultaneously capture the beauty and challenges of growing commercial citrus.”