Redefining the Language of Learning

W hile the English language may appear static, in truth, it’s always evolving. Originally derived from German and French, forms of English spoken in the United States have been shaped by Native Americans, enslaved Africans and their descendants, and successive waves of immigrants over many generations. More than just words, language is intrinsically tied to identity and learning. Keeping historical and cultural context at the forefront, UC Riverside professors are offering new insights and strategies for embracing language as it has evolved in Black and Hispanic communities in the U.S. to foster more equitable learning and acceptance in and out of the classroom.

Claudia Holguín Mendoza, an associate professor of Hispanic studies, and Jorge Leal, an assistant professor of history, are developing curricula that embrace the use of Spanglish, a hybrid of English and Spanish, highlighting the language’s cultural and educational importance for Latino youth. Alice Lee, an assistant professor in the School of Education, has found that recognizing students’ Black Language skills allows them to learn more effectively, and she has outlined ways for its use in the classroom. Using what they’ve learned, they are on a mission to reshape the language of education.

Reclaiming Heritage

UCR professors are linking history, culture, and language in new curricula embracing the use of Spanglish

By Sandra Baltazar Martínez | Photos by Stan Lim

S panish is the second most spoken language in the United States and fourth most spoken language in the world. Pop singer Becky G knows it. Prince William and Kate’s children know it too.

And for many younger generations of U.S.-born Latinos, now is the time to reclaim the language and embrace their bicultural, bilingual identities. This is a 180-degree shift in cultural acceptance compared to Latinos and Chicanos who grew up in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s and were forced to suppress their biculturalism in public for fear of discrimination or, in the case of school children, physical punishment. Many Latino youth nowadays are speaking Spanglish, a hybrid linguistic system between English and Spanish. Spanglish is a way of being, of belonging, and it’s making its way to television as well as college campuses.

At UC Riverside, professors are researching and developing curricula for K-12 and college courses that embrace and explain the importance of speaking Spanglish. Claudia Holguín Mendoza, an associate professor of Hispanic studies, focuses on sociolinguistics and Spanish heritage language education. Jorge Leal, an assistant professor of history, is a cultural and urban historian whose research examines how transnational youth cultures have reshaped Southern California Latino communities in the late 20th century. Together, the pair are leading the charge with grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and National Endowment for the Humanities.

“Years back, if someone said you spoke Spanglish, it was a derogatory label,” Holguín Mendoza said. “But now the community has reclaimed it as something prideful because language and culture shape our identity. Critics also need to understand that speaking Spanglish is not just speaking in any way you want; the language has cognitive logic and it’s also important to know the historical context.”

The Impact of Spanglish

Why is it important for some Latino communities to speak Spanglish? From a historical standpoint, Leal said, language imposition is one of the primary ways colonizers have overpowered nations (in addition to armies, of course). Therefore, speaking Spanglish is a way in which younger Latino people are reclaiming their heritage and embracing the full scope of their identities.

“Our communities have always been plurilingual,” said Leal, referring to a person’s ability to not only speak multiple languages but switch back and forth between them. “Latinx people have been speaking Spanish and Spanglish for generations. It’s a language that continues to evolve — it has been doing so for centuries, from colonization to now. I also push against this notion that Spanish is a ‘foreign language’ because it has been spoken here for centuries.”

According to U.S. census data, within a 40-year span, the number of bilingual people tripled from 23.1 million in 1980 to 67.8 million in 2019, far outpacing the overall population growth. In the U.S., English is the primary spoken language, followed by Spanish, Chinese, Tagalog, Vietnamese, and Arabic.

“I also push against this notion that Spanish is a ‘foreign language’ because it has been spoken here for centuries.”

— Jorge Leal

Accepting Spanglish as a language is also a means of validating the diverse cultures and experiences of U.S. residents. Forcing “English-only” disregards an intrinsic part of some communities’ identity. Latino children attending K-12 schools rarely, if ever, see themselves in history books or as characters in novels. Until two decades ago, the majority of the Spanish courses offered in college were taught by professors who only acknowledged the form of Spanish spoken in Spain as the “correct” way of writing and speaking. For Leal, this begs the question: Who is telling our young people their language is incorrect or less than?

“At UCR, we want to teach our students to feel proud of being plurilingual and that they belong,” Holguín Mendoza said. “We want to let them know that speaking Spanglish is a point of pride. To say, ‘I am trilingual, I speak English and Spanish and Spanglish,’ is prideful.”

The Power of Language

Holguín Mendoza is principal investigator for “Critical Sociocultural Linguistic Literacy,” a multimillion-dollar research project under UCR’s Latino and Latin American Studies Research Center (LLASRC). The project focuses on countering the systematic racism directed against Latino language and knowledge. It aims to dismantle testing and curricula policies that discredit Latino speech. Holguín Mendoza also collaborates with faculty at CSU East Bay, University of Wisconsin, University of Oregon, and Western Illinois University.

Re-envisioning what curricula can look like is part of the research conducted in the Latina/o Critical Race Theory Lab, or LatCrit Lab, within the LLASRC. The LatCrit Lab focuses on the critical study of Latino identities and currently facilitates six research projects led by faculty across the U.S. and Baja California. The lab seeks to demonstrate that Spanish-English bilingualism used in Southern California and other parts of the U.S. is not a broken form of Spanish or English, but rather a complex set of linguistic practices that reflect a vibrant borderlands culture and knowledge base.

“Speaking Spanglish is a point of pride. To say, ‘I am trilingual, I speak English and Spanish and Spanglish,’ is prideful.”

— Claudia Holguín Mendoza

At UCR, Holguín Mendoza and Leal are working with Adrián Felix, associate professor of ethnic studies, and Covadonga Lamar Prieto, associate professor of Hispanic studies and current interim associate dean for student academic affairs for the College of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences. Together, they are redesigning the curriculum for the Latino and Latin American Studies major and minor. The new curriculum aims to capitalize on students’ familiarity with Spanish to teach them deeper skills for engagement with historical, political, and cultural texts; push them to analyze the relationship between language and power; and reaffirm their bilingual abilities. Other UCR partners include Alejandra Dubcovsky, professor of history; Juliette Levy, associate professor of history; and the UCR Library.

“We are very lucky to know that our colleagues are revamping their courses, that the curriculum has integrated methodologies and interdisciplinary content; they are thinking of language centrally,” Holguín Mendoza said.

Research into Practice

In the coming quarters, some UCR students will start to see Spanglish in their curriculum. This is not a new phenomenon; eight years ago, according to a New Mexico State University survey, more than 40 colleges across the U.S. were incorporating Spanglish into their courses.

This research is also being implemented in the community. In May 2023, the researchers organized the Teach in Spanglish Symposium. More than 100 educators from K-12 schools, community colleges, and universities attended. Among the attendees was AP Spanish teacher Cristina Sánchez. Sánchez has been teaching for 16 years and is currently obtaining a doctorate in UCR’s School of Education. Her research, which intersects with the LatCrit Lab, focuses on heritage education at the high school level.

“Language is intrinsic to identity. It is not simply teaching Spanish, it is teaching identity and embracing all students from all backgrounds,” Sánchez said. “My goal is to have a student-centered classroom, not a teacher-centered classroom.”

As a teacher, she wants to humanize the academy, she said. Sánchez and other UCR graduate students, who are also current teachers, have created a curriculum that welcomes everyone into a conversation related to a lesson. For example, they use testimonios, or testimonies, quick writing exercises meant to create a safe space to share thoughts and uncover any racist connotations to language.

“I want my students to understand how language functions in society and why,” Sánchez said. “I tell my students, ‘I’m not bringing this information to the classroom to change who you are and who you want to be.’”

She emphasizes that providing historical context to language is crucial to teaching students to be confident in their language skills, regardless of how they pronounce words or if they speak Spanglish. She also includes well-known figures in her curriculum, like pop star Becky G, who she said is a good example of a third-generation Latina proudly showing young people “this is who I am.”

“Decades ago, we had drastic numbers of Latinos dropping out of school because they didn’t fit in. We had an understanding that ‘who I am does not belong in school’ — it was unspoken, subconscious,” Sánchez said. “But now we have a new generation. There is an awakening of ‘yes, I am different and that is good.’ There is a reconnection and revitalization to language.”

Spreading the Word

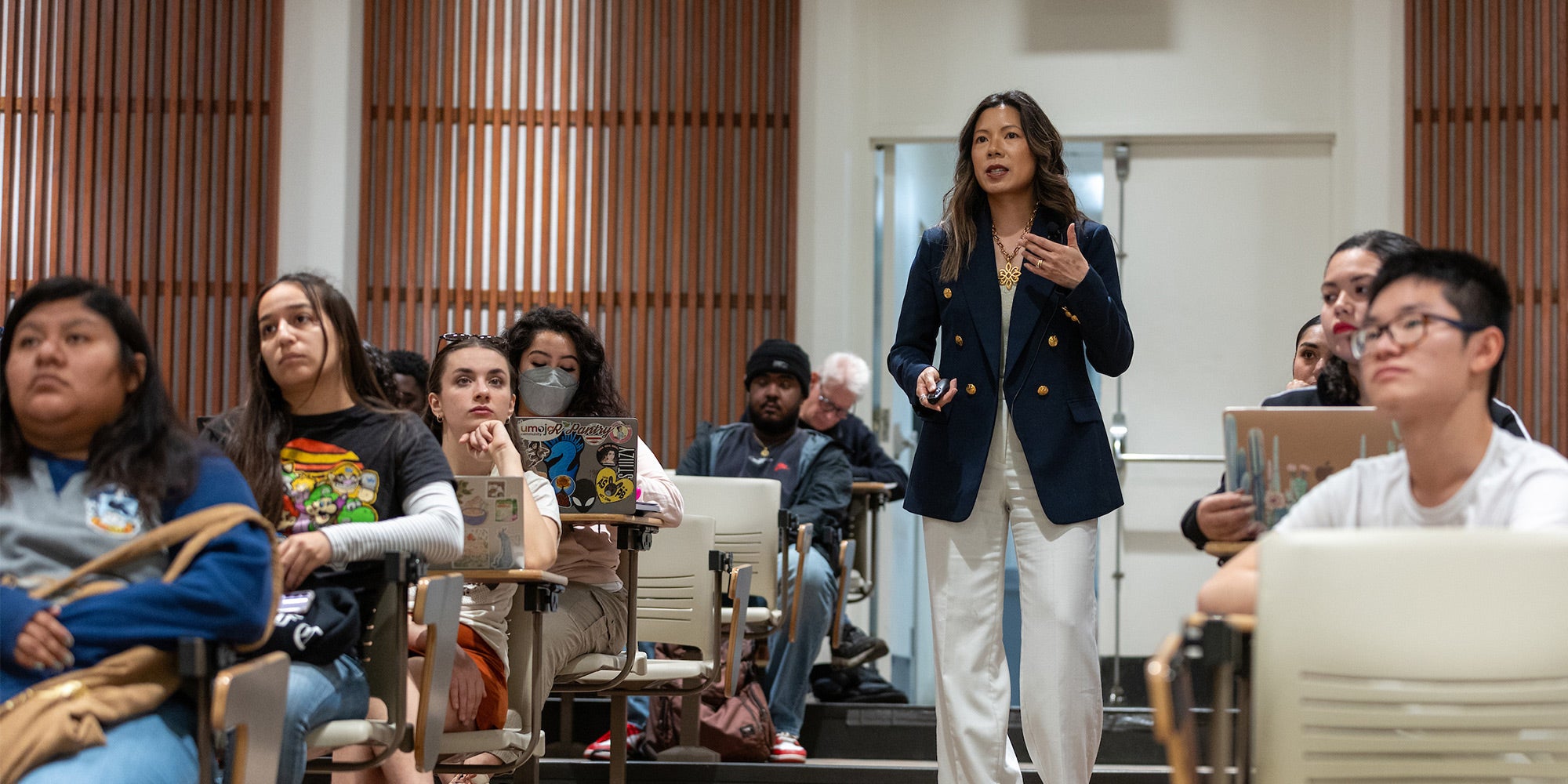

UCR language scholar Alice Lee explains why ‘correcting’ Black Language in the classroom is counterproductive to student success

By David Danelski | Photos by Stan Lim

I f you’ve ever jammed to a favorite song, kept it real with friends, or were hustlin’ to get all your work done, you’ve used Black Language but probably didn’t acknowledge it as such. Alice Lee, an assistant professor of critical literacy in UCR’s School of Education, credits this disconnect to a long history of colonialism and anti-Blackness that still shapes how we view Black people and Black Language.

As a Chinese American growing up in a small, predominantly white town, Lee’s young adulthood was fraught with racism. Throughout middle and high school, she faced daily bullying, intimidation, and othering by almost everyone in her class.

“I’ve spent the last 20 years trying to understand and make sense of the overwhelming racism I experienced in my first 20 years of life. Learning about ‘white supremacy,’ ‘microaggressions,’ and ‘colorblindness’ gave language to my experiences,” Lee said.

Lee became an elementary school teacher while simultaneously earning a doctorate in language and literacy from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. There, she delved into the origins and equity issues of Black Language — a distinctive language system that many African Americans use in daily conversation. This pivotal time was a “dance between theory and practice” in her own classroom.

“I couldn’t understand how half a century of linguistic research was unacknowledged in all our school curricula and practices,” Lee said.

She was staggered when school leaders told her Black Language was inappropriate for learning environments. In the school where Lee taught, the classes for students deemed to have higher-level skills were disproportionately white, while lower-level tracks were disproportionately Black. When Lee shared her learning of Black Language with a white colleague, she recalls him saying, “These kids can’t even talk right, how am I going to teach them math?”

Since then, Lee has been working with scholars across the country to change school structures that work against Black Language speakers. To do that requires challenging a long-held and misguided belief that “correcting” a student’s language to mainstream English will set them up for future success.

“My original quest to understand why Black Language is ignored and devalued in schools led me to the deep inner work of confronting my own anti-Blackness, and to also consider major roadblocks for Black Language speakers in classrooms,” Lee said.

Understanding Black Language

Originating as a form of communication between enslaved Africans from differing cultural backgrounds in the pre-Civil War South, Black Language has been studied and written about by scholars and linguists for decades. The language uses words and structures of African origin and has unique communication patterns, such as call and response — an energetic back-and-forth between speaker and audience commonly used in Black churches, public gatherings, and music. Like any other language, it follows specific grammar rules and structures.

Black Language is spoken widely in African American communities and homes across the country, but also has geographic variations. It has been referred to as African American Vernacular English, Ebonics, and Black English, but Lee defers to current Black Language scholars who acknowledge the African roots of the language and connect it with racial identity.

The language also has the ability to sum up complicated ideas in few words. Just how many English words does it take to translate the meaning of 20th century Black novelist Zora Neale Hurston’s famous quote, “All my skinfolk ain’t kinfolk,” to nuance familial and racial belonging? Such succinctness hasn’t been lost on the nation’s $360-billion-dollar advertising industry. Consider Coors Light’s “Made to Chill” ad campaign, Coca-Cola’s “Everybody Chill,” and Etsy’s “Let’s Get Lit” line of products. Even former President Richard Nixon took advantage of such an economy of words by using the terms right on, rip-off, chill out, and dis in his speeches. But while the mainstream public has appropriated Black Language in many settings, it is still relegated to the ranks of slang in schools. Lee says this hypocrisy shows how negative views of Black Language have more to do with race than with language.

A Forbidden Learning Tool

As U.S. schools continue to devalue Black Language, bilingual children are being forced to learn with only roughly half their language tools, Lee said. What’s worse, school language skills assessments that consider only what Lee calls a child’s “white mainstream English skills” result in bright students being placed in lower-track classes, which can compromise their learning potential and wrongly label them as underachievers. Language is the primary vehicle for learning, she said.

“Not allowing students to use Black Language to learn is like forcing someone to build a home with only half their tools,” Lee said. “Forbidding Black Language in classrooms sets Black students up for failure.”

The focus in the early grades on phonics instruction and oral fluency tests — which count the number of words students read and pronounce correctly within a short amount of time — inaccurately assesses many Black children, Lee said, since only mainstream English words and pronunciations are considered correct. Students will get marked down for using Black Language grammar structures, such as making a word possessive without an apostrophe. “Johnny book” instead of “Johnny’s book” would be marked incorrect even though it is correct in Black Language grammar.

“It turns out that what some refer to as the ‘science of literacy’ isn’t so scientific after all, especially when they ignore linguistic science,” Lee said.

Such assessments also have grave consequences for student success. Research has shown that once a child is placed in a lower-level class, it can compromise their educational outcomes. Students in lower-level tracks often receive lackluster lessons in phonics and grammar structures and schools have lower expectations for academic success. Meanwhile, higher-level classes have more challenging and inspiring curricula and more fun with creative projects.

Advancing Black Language Scholarship

With grant funding from UCR through the Regents Faculty Development Grant, the prestigious Spencer Foundation, and other sources, Lee’s research focuses on the learning rights of young Black Language speakers, the need for more Black teachers, and confronting anti-Blackness within Asian and Asian American communities. Her work, published in top research journals like Research in the Teaching of English, highlights the shortfalls of current literacy skill assessments and offers practical strategies for incorporating Black Language into curriculum and instruction. The work compelled the Literacy Research Association to recognize Lee with the “More Just World” award in 2022.

“Not allowing students to use Black Language to learn is like forcing someone to build a home with only half their tools.”

— Alice Lee

Lee is also advancing Black Language scholarship through UCR’s first undergraduate course on the topic, which she taught last fall. Several of her students were so moved by the experience that they joined a Black Language research consortium created by Lee. Eight Black students are now collaborating with Lee on research papers that draw from their personal experiences and the academic literature. Other undergraduates are working on papers about Black solidarity from Latino and Asian communities. The consortium is working with local teachers and administrators to host community forums for Black families.

“My vision is to showcase the academic brilliance and beauty of Black Language speakers through critical, diverse research methods,” Lee said. “By working to convene multiple community partners, I plan to build pipelines of Black teachers, school leaders, and Black Language scholars in Southern California.”

Lee wants to see more teachers from African American communities, noting one of the primary roadblocks is the lack of teachers who can understand the language and use it when teaching students.

“The life experiences of Black teachers are imbued with rich language, histories, and ways of knowing the world that then get lived into how they teach in their classrooms,” said Lee, whose theory “Teacher Embodiment as Lived Pedagogy” explores this very topic.

“The terms ‘culturally relevant’ and ‘culturally responsive’ literally came out of studies about mostly Black teachers and their ways of teaching,” she said.

Lee hopes for a future when bilingual students are given full credit for the full scope of their language skills and are allowed to use them for learning. Yet, U.S. schools have a long way to go.

“I am working towards a future in which Black students are able to utilize all their resources to learn,” she said. “I am committed to building fiercely and fearlessly, and I invite partners across the state and country to join me in this exciting movement.”

What is “Standard English”?

Black Language has been suppressed as a learning tool in U.S. schools under the argument that it impedes the learning of “standard English.” But Black Language scholars, such as April Baker-Bell, have long pushed against the term “standard English,” Lee said, and she and other scholars instead use “white mainstream English” to describe the dialect of English determined by dominant white communities. Lee asserts that imposing one standard dialect of English is a vestige of colonialism and white supremacy that dates back to the European colonial conquest of Indigenous peoples. Languages became tools for domination, she said, forming cultural hierarchies; English and other European languages were deemed correct and superior, while the languages of the conquered or enslaved people were deemed wrong and inferior.