OFFICE HOURS

A Safe place

Through her research and advocacy, psychology professor Tuppett Yates is transforming the lives of at-risk youth

By Sarah Nightingale | Photos by Stan Lim

I n the movies, proud parents drop their college-bound kids off on scenic campuses and welcome them home when dorms close for holiday breaks.

“There’s an assumption that students have families to go home to,” said Tuppett Yates, a professor of psychology and founder and executive director of UCR’s Guardian Scholars Program. “But that’s not always the case.”

Students who are self-supporting or aging out of the foster care system are among those who don’t have a parental home to go back to. Thirty years ago, in her first year at Brown University in Rhode Island, Yates was one of those students. Having left home during high school, Yates arrived at college utterly alone. Despite her love for learning and excellent grades, housing and emotional stressors prompted her to drop out after just one semester.

Fortunately for Yates, a professor reached out and motivated her to continue her studies. The mentor was one of a handful who helped Yates through high school and college, telling her, “I think you can go places.” And Yates did — earning a bachelor’s degree in neuroscience and psychology from Brown University followed by a joint doctorate in clinical science and developmental psychology from the University of Minnesota. With integrated training in both clinical and developmental psychology, Yates was a coveted candidate when she entered the job market in 2006. She interviewed for 16 assistant professor positions before choosing UCR.

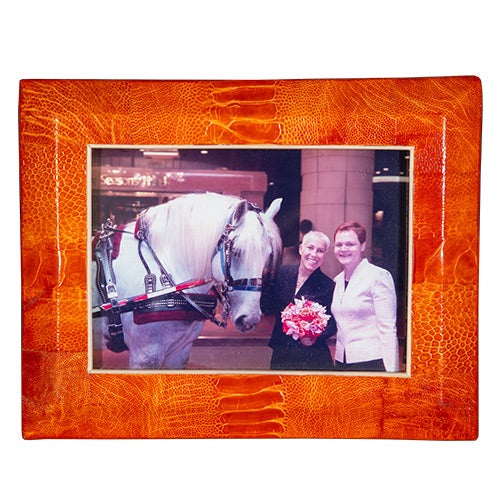

“UCR was the first place I visited where I really felt safe,” said Yates, who is the current chair of the psychology department. “I’m tatted, shaved-headed, and queer. People at UCR respect you for what you do, and how you engage with the world, your students, and your colleagues. That’s why I came.”

Yates stayed, she said, because of the students.

“I love our students,” she said. “They are truly the gold that makes this place sparkle.”

Like all new professors, Yates scrambled to set up her research program, which focuses on how adverse childhood experiences affect development and informs best practices for policymakers, clinicians, and family court judges. Through two large longitudinal studies — one following 250 children growing up in Riverside County and one tracking young adults aging out of the foster care system — Yates is exploring how children see themselves and others, how they navigate close relationships, and how they regulate their emotions and bodies to cope with life experiences like poverty, discrimination, and family violence. Her work emphasizes the high price children pay when they experience adversity.

“Kids who appear to be resilient and have a high capacity to recover from challenges can have worse physical health outcomes than children who are struggling behaviorally,” Yates said. “What that means is that adversity doesn’t make you stronger, it just hurts different kids in different ways, and resilience is not all-or-nothing.”

Yates’ current National Science Foundation grant explores if and how childhood aggression in contexts of adversity may buffer children from experiencing physical health problems later on.

“If kids’ aggressive behaviors serve a protective survival function, we won’t be able to reduce them unless we help kids meet those needs in a different way,” she said.

In addition to her research, teaching, and mentoring students, Yates is passionate about helping one of UCR’s most academically at-risk populations: students transitioning to college from the foster care system. The Guardian Scholars Program she founded in 2008 has grown from three students to 37 and provides a wrap-around network of resources to students who are in extended foster care or have aged out of the system.

“It’s like a buffet,” Yates said of the program’s offerings, which began with year-round, on-campus housing and include financial and academic support, health and wellness resources, holiday celebrations, graduation photos, and social activities — the things most students get from their families. “Some students make use of every resource we have, others never show up until they need a root canal and our emergency medical fund.”

In 2015, with grant and donor support, the volunteer-led program hired a full-time director and opened a physical resource center in Bannockburn Village. The same year, the Guardian Scholars Program was brought under the umbrella of UCR’s Office of Foster Youth Support Services, also founded by Yates, which offers resources to the nearly 200 UCR students who spent 24 hours or longer in foster care at any age.

With more than 60 graduates, Guardian Scholars are giving back to their communities as doctors, teachers, lawyers, social workers, and entrepreneurs. Many have gone on to form safe and successful partnerships and families.

“It was amazing mentors who saw through the noise of my struggles and realized there’s music that they could amplify for me,” Yates said. “I’m doing the same with our foster youth. They are incredibly bright, passionate, and naturally predisposed toward social justice. They’re exactly who we need in this world, and they don’t need heroic efforts to thrive. They just need a little bit of what most students already get.”

With a gift of any size, you can uplift Guardian Scholars and ensure access to basic needs like education, housing, and health care. Give today at donate.ucr.edu/spring2025.

Return to UCR Magazine: Spring 2025