LIVING THE CALIFORNIA DREAM

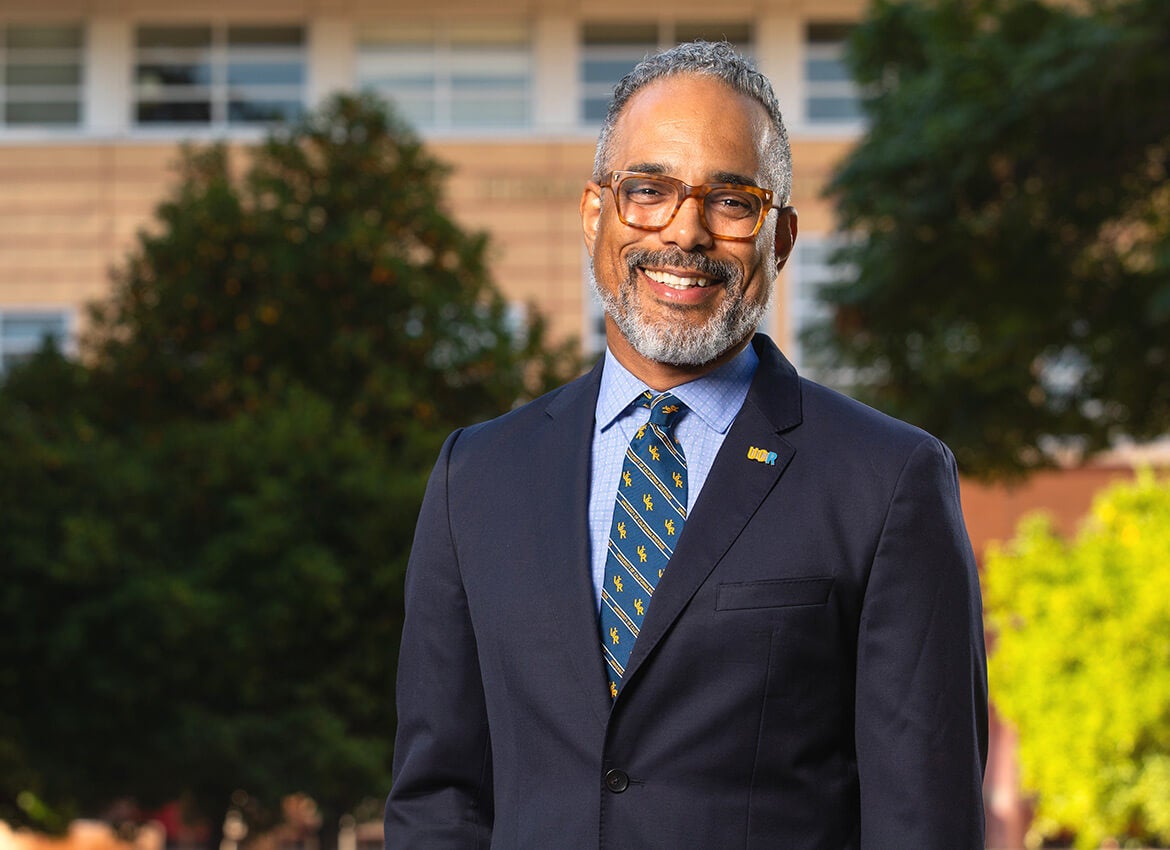

Dean Daryle Williams balances his work in illuminating the history of enslaved peoples with leading the largest college at UCR

By Tess Eyrich

or Daryle Williams, arriving at UC Riverside in fall 2021 represented the culmination of a series of personal breakthroughs. Among those: a long-awaited homecoming to his native state, the realization of a California Dream that places public higher education at the fore, and a profound opportunity to reclaim parts of his identity that had previously been glossed over.

Amid a seemingly never-ending pandemic, Williams succeeded sociologist Milagros “Milly” Peña as dean of UCR’s College of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, or CHASS, last September. A historian by training, he has spent the majority of his career on the East Coast, first earning his bachelor’s degree from Princeton University and later spending 27 years as a faculty member and administrator at the University of Maryland. As a former Pell Grant recipient who participated in the Federal Work-Study program while at Princeton, Williams said he very much identifies with the experiences shared by many UCR students. More than half the students in CHASS — the largest of UCR’s seven colleges and home to 47% of all UCR students — are Pell Grant recipients, while nearly 60% identify as first-generation students and 44% identify as low-income.

Still, Williams confessed, “I was very much socialized out of thinking of myself in those ways. [As an undergraduate,] I went to a very wealthy, prestigious institution — Princeton — and then for graduate school I went to Stanford, which was, again, very wealthy, very prestigious, and historically very predominantly white.”

Being at UCR, he added, has encouraged him to reconnect with parts of himself: “It’s been a personal journey, but also a journey of understanding what UCR is and what it’s doing — the who and the why.”

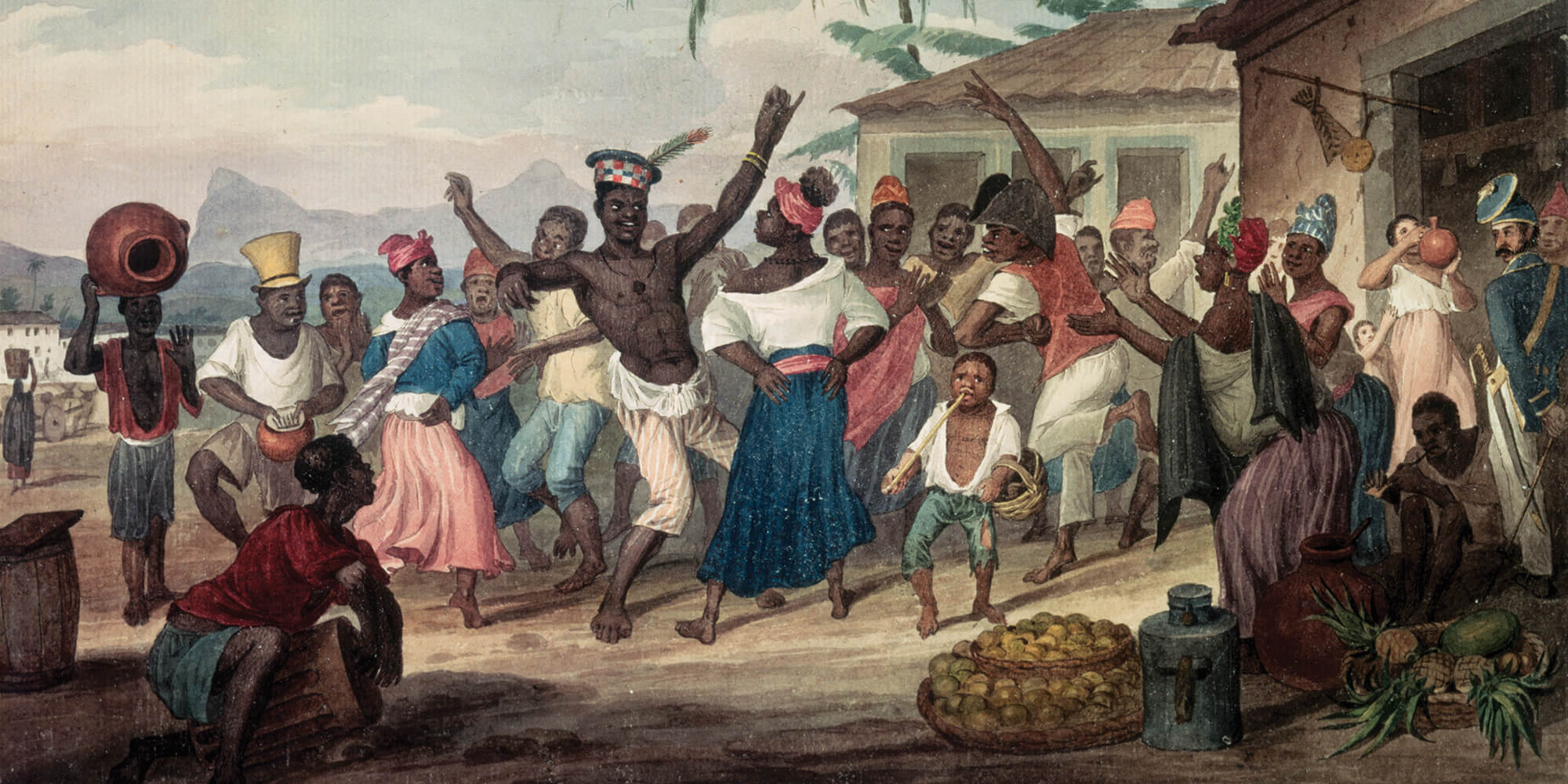

(Courtesy of Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora)

Origin Story

Born in San Francisco, Williams moved with his mother to San Diego when he was 7, landing first in the city before relocating inland to East County. The pair lived in “what’s now called backcountry,” according to Williams, “hot, dry, and semi-mountainous — it’s amazing we didn’t die in a wildfire.” He attended Valhalla High School in El Cajon in the early 1980s, traveling about 40 minutes by bus each way.

“To be honest, I just wanted to get out and see a lot more of the world,” Williams said.

Admission to Princeton provided just the escape route. Williams’ first day of college at the private, Ivy League institution in small-town New Jersey, was also his first day on the East Coast — and the start of a period of significant cultural adjustment.

“I had never seen the campus before except in pictures,” he said. “And I had never been around people who went to these schools I had heard about in movies, like Deerfield and Dalton. A Rockefeller was in my class — to me, that was just weird.”

Williams expressed boundless gratitude for his experience at Princeton but said he holds some complicated feelings about his time there. The environment, he said, could be “insular,” “conformist,” and “very repressive,” especially for a young gay man who hadn’t yet come out. Still, Princeton afforded countless opportunities, including in the research realm. As a budding historian focused on Latin America, Williams received funding to first participate in a summer research program at Stanford University between his sophomore and junior years, then headed to Brazil between his junior and senior years.

With the exception of prior jaunts to northern Mexico, the trip to Brazil in 1988 constituted Williams’ first experience abroad. In Rio de Janeiro, he worked out of sites like the National Archive of Brazil, studying the country’s mid-20th-century history and exploring “questions of culture and the state.” Williams described his training as having “sort of a classic intellectual formation”; as what’s now commonly known as a “Brazilianist,” he was taught primarily by North American scholars who had begun to study Latin America around the tail end of the Cold War.

“Brazil is such a large country, like the United States,” Williams said. “Territorially and population-wise, there are so many different questions one can ask about Brazil. It can also have its own particular sort of exceptionalism, similar to how we think about the U.S.”

Something Williams’ training didn’t include: exposure to the digital humanities, or the application of digital resources and technologies to humanities disciplines. It wasn’t until many years later that Williams first began to understand how to integrate digital tools into his research to help it come alive for and become more accessible to the public. By then, he had shifted his research focus to 19th-century Brazil, including the history of Atlantic slavery and emancipation in the country. He realized that elements of a research project he was working on contained addresses that could be digitally mapped. Over time, that realization would lead to the development of perhaps the most ambitious research endeavor of Williams’ career: the digital database found at Enslaved.org.

Fragments of a Whole

Launched in its current iteration in December 2020, “Enslaved: Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade” brings together nearly one million records related to the historical enslavement of Africans. To date, it includes information on nearly 600,000 people — enslaved Africans; their enslaved descendants; former enslaved people; and individuals involved in the sale, employment, control, or releasing of enslaved people, among others — as well as places, events, and sources.

Backed by around $4 million in financial support, mainly from the Mellon Foundation, the project has bloomed into a robust, well-resourced operation, said Williams, who is co-principal investigator. The full team now includes 10 to 12 permanent staffers, plus postdoctoral researchers, graduate fellows, and undergraduate summer researchers. That translates into historians, humanists, and archivists working alongside data scientists, information studies specialists, programmers, and back- and front-end designers who sculpt the Enslaved.org interface to make it accessible to a broad public audience.

How it works: The Enslaved.org team uses datasets — essentially, spreadsheets of “cleaned” data lifted from primary source materials, such as ship manifests, bills of sale, birth or death certificates, baptismal or marriage records, runaway advertisements, and emancipation documents. Some of the information comes from partnerships with other large-scale digital research projects or databases, like SlaveVoyages, the Legacies of British Slavery, and the Louisiana Slave Database. Enslaved.org researchers may also collaborate with smaller-scale operations — think one or two archivists — or with heritage sites such as the former presidential plantations Monticello or Mount Vernon. Both the datasets and the processes involved in compiling them are then chronicled in the digital Journal of Slavery and Data Preservation, of which Williams serves as editor-in-chief.

By breaking the information found in primary source materials into bite-size fragments, the data scientists at Enslaved.org are able to put sources in conversation with each other, providing multiple touchpoints for visitors to learn about the events of an enslaved individual’s life and the context in which it was lived. Williams described the effort as an attempt to grapple with slavery as “a violent form of stripping individuals away from everything knowable about them” by giving them back some of their humanity.

While much of what can be found on Enslaved.org consists of “truly fragmented information — cells on a spreadsheet,” according to Williams, the contents nonetheless have many potential uses for scholars, archivists, and genealogists, particularly Black family historians. In addition, the Enslaved.org team recently began expanding the platform’s offerings for K-12 educators, including written biographical narratives that align with curriculum and can be easily woven into lesson plans.

“One of the biggest challenges is that people tend to work with this expectation that the research process is magical and mystical, and that it takes you to places where you find what you’re looking for, not dead ends — not fragments, but whole stories,” Williams said. “We need to be upfront with people that we may not be able to, for example, find who they believe to be their ancestor. But we potentially might be able to provide an understanding of the environment in which they lived, or the possibilities of that particular life based on something that’s comparable in place and time or historical experience. The goal is to provide context, and to provide that context in a way that is open-access and open-sourced — no registration or pay involved. Truly public.”

(Courtesy of Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora)

NEW HORIZONS

Moving forward, Williams wants UCR students, especially undergraduates, to get involved in the effort that goes into producing Enslaved.org.

“That might help us to shape some of the conversations about how we look at California and the U.S. West or Southwest as places of enslavement,” he said. “There are a lot of narratives about how there were no slaves in California, but that’s not true.”

Likewise, Williams may collaborate with other UCR faculty members to apply some of the techniques associated with Enslaved.org to other historical contexts and source material, such as those related to the California mission system and the Indigenous people who built and lived on and around them.

Beyond getting the UCR community involved in the Enslaved.org effort, Williams has myriad intentions for CHASS and the campus at large that he hopes to see crystallize in the coming years. Of chief importance is gaining membership into the Association of American Universities, or AAU, an organization of 65 of the most prominent research universities across the U.S. and Canada. Of the nine UC campuses that educate undergraduate students, seven are recognized as AAU members.

“We should be in that group because of our research endeavors, our research talents, the type of research we do, and where we do it,” Williams said. “There’s a great opportunity for CHASS to play a leading role in demonstrating to the powers that be that UCR is of that caliber.”

Williams is forthcoming about the need to address the disruption for students wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Many of our students have experienced a significant portion of their studies not physically connected to a campus,” he said. “They haven’t been able to experience some of the planned and unplanned things that happen when they’re in a classroom or a laboratory together. There have been fewer opportunities to grow as and in a community.”

Williams recognizes that a significant part of his role is concerned with community-building — for students and faculty alike to see themselves as part of both UCR and Riverside more broadly — and then to transform those environments. Fortunately, the liberal arts education provided by CHASS serves as a rich environment for exactly the type of growth he envisions.

“Liberal arts train you, they prepare you, they put you in the right conversations and networks,” Williams said. “You acquire the social capital and capacities to both communicate effectively and listen to how others communicate and approach that in a critical, engaged way.

To put it even more simply: You learn how to do storytelling and are exposed to all kinds of different stories, too.”

A Summer to Remember

“When I was a student, summer research programs were very transformational for my own research journey,” Williams said.

So, it comes as no surprise that offering a summer research opportunity for undergraduates to “live, grow, and work collaboratively through problems” is a priority for Williams amid his tenure at UCR.

Over the past summer, seven undergraduate students from around the country were selected to participate in the 2022 Enslaved.org Summer Research Opportunity Program. The cohort — which included one representative from UCR, recent graduate Viviana Martinez ’22 — began its seven-week residential experience at the University of Maryland in June before spending a final week at the UCR Palm Desert campus.

The intensive program was designed to introduce participants to methods of data-informed historical research like those employed by the Enslaved.org team. It also challenged the young researchers to produce a dataset publication about the lives of enslaved people living in Maryland and the District of Columbia using a single source document titled “List of Slaves Belonging to the Estate of Thomas Cramphin Deceased that are Hired Out.”

Beyond serving as an entry point for the UCR community to assist with research related to Enslaved.org, Williams said he hoped the experience would help students not familiar with UCR to come to view it as “a place of opportunity, of research, and of possibility.”

He added, “Two of our participating students [were] from California, but five [were] from other places, so this [was] a life experience for them, too. It can have a transformative impact on individual scholars.”

Victorville, California, native Viviana Martinez ’22 earned a bachelor’s degree in history from UCR in spring and aims to enroll in a master’s program in history this fall. Below, she shares her experience taking part in the Enslaved.org Summer Research Opportunity Program.

“I was given the opportunity to live in Maryland alongside a diverse group of peers, while researching the state’s history from primary sources. I was able to meet various faculty members and professionals who gave me great advice on history research and my personal academic endeavors. I also learned from the various mentorship and workshop opportunities on graduate school, and they offered us many resources to assist us throughout our application process. It was such a life-changing experience. I cannot thank Dean Williams enough for his mentorship and this opportunity!”

Return to UCR Magazine: Summer 2022