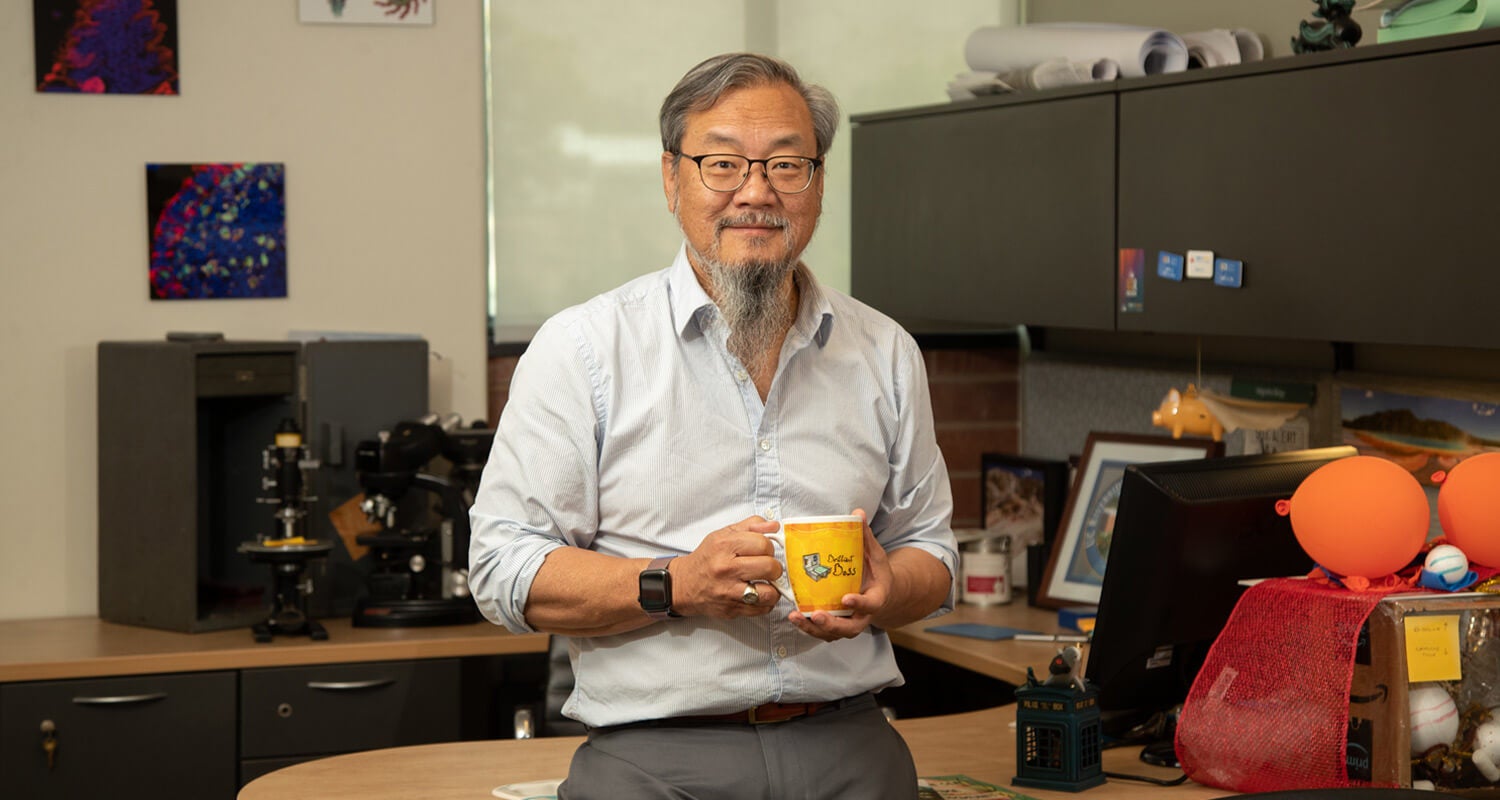

OFFICE HOURS

LO AND BEHOLD

Vaccine expert Dr. David Lo’s research interests range from immunology to addressing health disparities

By Iqbal Pittalwala | Photos By Stan Lim

he first thing you might see through the window in Dr. David Lo’s office in the School of Medicine’s Education Building is the giant yellow “C” reclined on Box Springs Mountains in the distance. But then your eye moves swiftly to the interior of his office, to the panoply of objects — microscopes, wall art prints, a model of a flying pig, and a peculiarly shaped ashtray — this distinguished professor of biomedical sciences and senior associate dean for research in the School of Medicine has collected over the years.

Hailing from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, Lo graduated with a bachelor’s degree in biology from nearby Haverford College, then earned a doctor of medicine and doctor of philosophy degree in genetics at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. After graduating, he completed a three-year postdoctoral appointment at the university’s School of Veterinary Medicine, then went on to The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, as an assistant — and later, associate — professor. Lo later joined the San Diego biotechnology company Digital Gene Technologies as vice president of integrative biology, where he began focusing on vaccine development.

A world-class vaccine expert, Lo joined UCR in 2006 after leaving a position at the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology. Biology has intrigued him since he was a boy, he said, and while in college in the late 1970s and 1980s, he was convinced the most interesting biology lay in immunology, which was beginning to shape up as a distinct field of research. A number of fundamental questions about immunology still keep Lo up at night.

“How does it work?” he said. “There are so many moving parts in the immune system and because they can move all over your body, how do they interact? How do they communicate?”

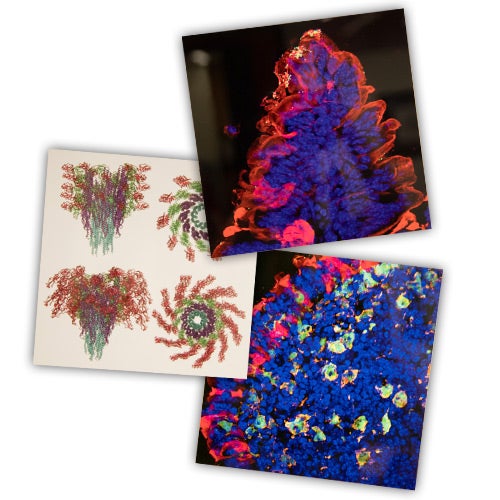

Much of this is not well understood, he said, and these moving parts react not just with other immune cells but with all the other cells in the body, further complicating matters. Researchers also believe that the bacteria microbiome in your skin, lungs, and gut, which is present even without infections, also interacts with the immune system. This prompts another question Lo wrestles with.

“Bacteria are always around, after all,” he said. “We tolerate all of them in our bodies, but, somehow, they don’t activate the immune system perpetually. Why not?”

Beyond his work in immunology, Lo co-directs the UCR Center for Health Disparities Research, which employs an interdisciplinary and community-based approach to advance understanding of health disparities challenging Inland Southern California, a rapidly growing and diverse region with a shortage of healthcare professionals. His own research is centered around the Salton Sea, the inland body of water straddling California’s Riverside and Imperial counties. In mouse studies, his lab, in collaboration with other researchers on campus, found Salton Sea aerosol turns on nonallergic inflammation genes and may also promote lung inflammation.

“Communities surrounding the Salton Sea show high rates of asthma due, possibly, to high aerosol dust levels resulting from the sea shrinking over time,” Lo said.

It may come as no surprise, therefore, to find a vintage ashtray shaped like the Salton Sea sitting prominently on his desk.

“I have never used it as an ashtray,” Lo said. “I’d have candy on it for visitors, but even that use came to an end when COVID-19 came around.”

Return to UCR Magazine: Summer 2022