LIVING ‘THE GOOD LIFE’ IN LITTLE ETHIOPIA

How an informal banking system is helping a Los Angeles community of Ethiopian immigrants thrive

By Holly Ober | Photos by Stan Lim

veryone wants to live “the good life,” but that means different things to different people — and there are many different paths to achieve it. For some, it means leaving your home country to follow your dreams in a strange new land.

UC Riverside anthropologist Worku Nida came to California from Ethiopia for graduate school at UCLA and has studied the Ethiopian immigrant community in Los Angeles for the past 20 years. In particular, he is examining the ways Ethiopian immigrants build transnational communities and institutions around entrepreneurial and religious practices, including Ethiopian churches and mosques.

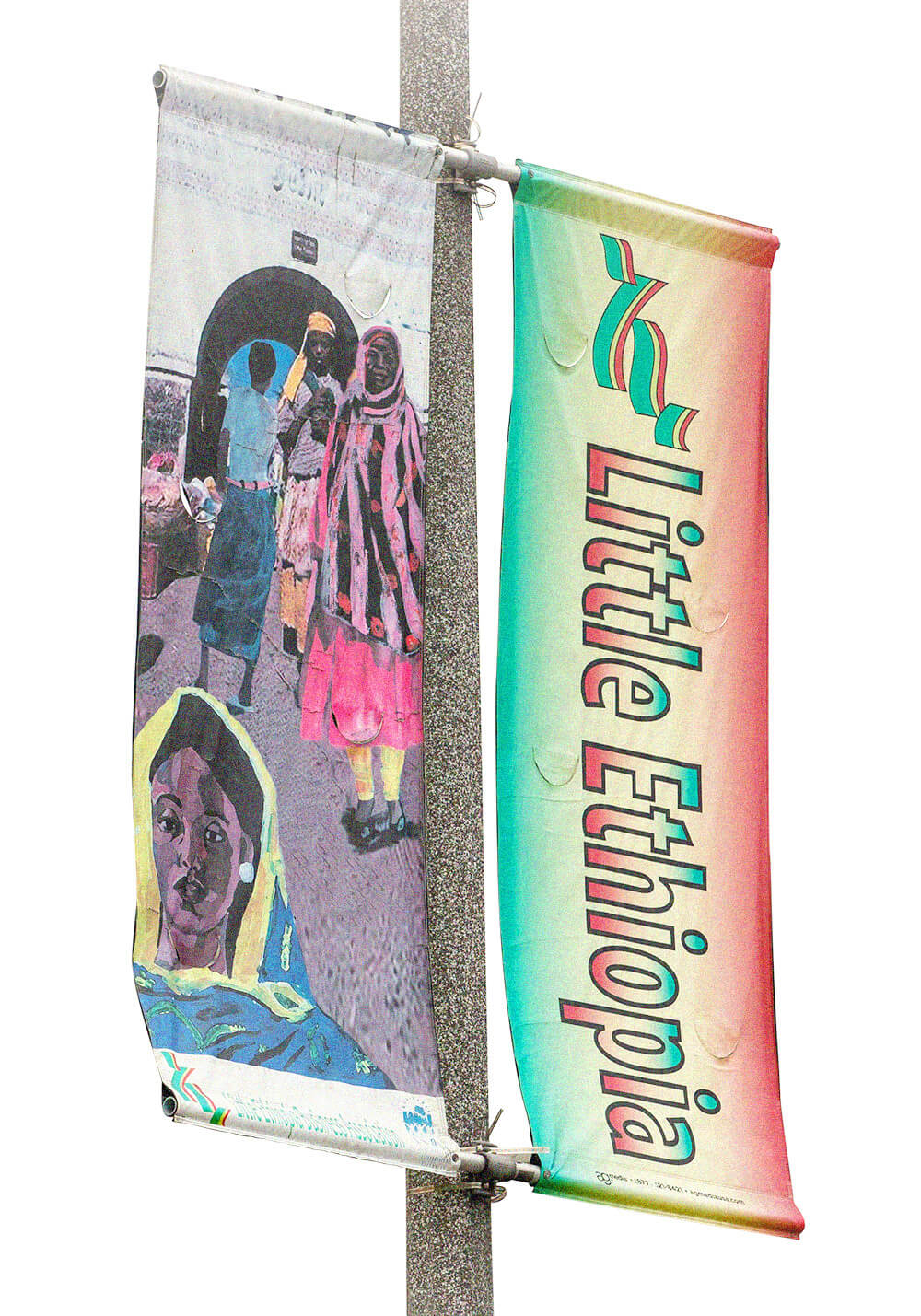

He is currently observing how immigrants are using an “informal” banking tradition to fund entrepreneurial activities that, over the past three decades, have raised a bustling, vibrant community known as Little Ethiopia in the heart of Los Angeles.

“I want to know how people in diasporic communities build their futures using traditional banking,” he said. “How do people use these institutions in the different cultural contexts where these communities exist?”

His work illuminates how a less than half-mile stretch of Fairfax Avenue once occupied by Jewish-owned businesses became a cultural hub for the 70,000-80,000 Ethiopians who call the Greater Los Angeles area home. The short answer is chain migration, what social scientists like Nida call an immigration pattern where early immigrants establish or find jobs, then encourage friends and family to join them, and, once they’re settled, these later immigrants do the same for others. Sometimes, whole industries or occupations can become ethnic “specialties” over time, especially when coupled with informal banking systems that help newcomers start businesses.

In Ethiopia, some companies owned by Europeans, Arabs, and other non-Ethiopians drew on a century-long tradition of chain migration that brought rural villagers from the Gurage ethnic group into Ethiopia’s rapidly modernizing cities as laborers and construction workers. The Gurage possessed a secret that would eventually help them elbow out foreign-owned businesses to become Ethiopia’s dominant merchant class: a banking system called equb. Social scientists call such systems rotating savings and credit associations.

Devised long ago by rural farming women, equb first involved pooling butter and distributing the caches between households for storage until it would be used to feed whole families during festivities. As a member of equb, every woman regularly contributed a small amount to a rotating series of storage households. The contributions acted as a credit that allowed a woman to borrow butter from the pool for her own use and pay it back later.

“Equb was originally for storing valuable village resources,” Nida said. “But what is valuable in a city? Money. So the men who migrated to cities for work adapted the women’s system to meet their new needs.”

Instead of butter, urban migrants made small, steady contributions to pools of money from which they could borrow in proportion to their investment. Using equb loans, the migrants started businesses, recruiting people from back home as employees. Some of these workers would also one day open businesses, inviting more villagers to work for them. The rotating banking system evolved to include insurance that helps businesses weather setbacks and risk.

“Gurage were originally brought to the cities by Ethiopia’s nobility and foreign-owned industries as essential labor for the cities,” Nida said. “Successful migrants started their own businesses, and within three to four decades, the Gurage replaced all the foreign companies. They became the quintessential businesspeople of Ethiopia and dominated the commercial sector. This created a domino effect. As their businesses grew, they created a need for more labor, which was filled by more Gurage from the villages.”

Non-Gurage Ethiopians living both in and outside Ethiopia soon also adopted equb, making it a universal institution. Wherever Ethiopians live, they are likely to practice equb.

When political and environmental crises drove Ethiopians to America in large numbers after 1974, they encountered a daunting financial system that makes it nearly impossible for people with no credit history or collateral to obtain loans. But after a period of making contributions, currently about $200 to $300 a week in Los Angeles, immigrants can request a loan from their equb. Like any other loan, these loans must be repaid in full, but, in Los Angeles at least, no interest is charged. And although no numeric credit rating is involved — the system operates entirely on trust — potential borrowers must earn the respect of other members of their equb for their loan to be approved.

The owner of one of Little Ethiopia’s core businesses offers a good example of how his community’s banking, credit, and insurance system works, and how it has helped to build Little Ethiopia itself.

Berhanu Asfaw runs Messob, a busy restaurant with luxurious decor and delicious traditional Ethiopian food. When he came from Ethiopia to Los Angeles for college, Asfaw was able to support himself as a transport dispatcher at an airport. After graduation, he worked in the electronics department of a hotel construction project. All the while, he had been contributing to an equb and used his first loan to buy a car to start a taxi service when the hotel was finished.

As his family grew, Asfaw knew taxi driving could not provide the future they imagined. He saw a need for more restaurants that offered Ethiopians the comforting dishes they missed from their homeland and knew that a successful restaurant could support his family and community. With another equb loan, Asfaw and his brother Getahun bought a restaurant together, which today occupies two storefronts on South Fairfax Avenue and serves a diverse clientele.

“People take out loans to pay rent or medical bills, buy a car, or cover unexpected expenses,” Asfaw said. “Equb is a community-based social safety net.”

Equb loans have helped Asfaw become a successful business owner, but the loans can be used for almost any purpose, and people can participate in more than one equb. In addition to the rotating banking, credit, and insurance system, Ethiopians have also developed a savings system called iddir to help people pay for funerals.

Most immigrants run up against America’s seemingly insurmountable lending barriers at first, and Ethiopians are far from the only immigrant community to invent rotating savings and credit associations or to adapt traditional savings and credit practices for entrepreneurial or social safety net ends. For example, the recent Netflix documentary, “The Donut King,” showed how chain migration and informal credit arrangements put California’s doughnut shops overwhelmingly in the hands of Cambodian families and stunted the spread of chains like Dunkin’ Donuts in the state.

Rotating savings and credit associations are so common in immigrant communities around the world that social scientists have given them their own acronym: ROSCA. Anthropologists study ROSCAs as robust yet highly flexible institutions that help immigrants carve a place for themselves in their new environments as well as support family and friends who remained at home. ROSCAs are a way of transplanting central cultural ideas about what is valuable and how people should treat each other.

“When immigrants are desperate for resources, they get creative,” Nida said.

Funded by a grant from the German Research Foundation, Nida is working with an international team of scholars to learn how Ethiopian immigrants are using informal savings and insurance associations in Ethiopia and the United States, Israel, and South Africa, where Ethiopians have established large diasporic populations. In Ethiopia, the research examines how informal savings and insurance associations facilitate emigration. Projects in the Ethiopian diaspora seek to understand how immigrants have adapted these financial practices to suit the different social, cultural, political, and economic circumstances unique to each community in pursuit of “the good life.” The work contributes to emerging interests within anthropology that seek to understand how people imagine, then attempt to create, good lives.

“People are using these rotating banking and credit systems to create new businesses and expand existing ones, and using these activities to create futures for themselves and their children,” Nida said. “But they are also investing in schools, roads, and other ventures in Ethiopia to build futures for people there.”

Return to UCR Magazine: Winter 2022