The Accidental Dissident

UCR Professor Perry Link is considered an enemy by the communist regime of China — by his account, he’s given them sufficient reason

By John Warren

“B lacklisted by the Chinese Community Party” is a badge of honor Perry Link has worn for almost 30 years. On any night, Link, a UCR professor of comparative literature, may be heard on Voice of America or quoted in The New York Times. He’s a leading voice on the human rights violations of the Chinese Communist Party, or CCP.

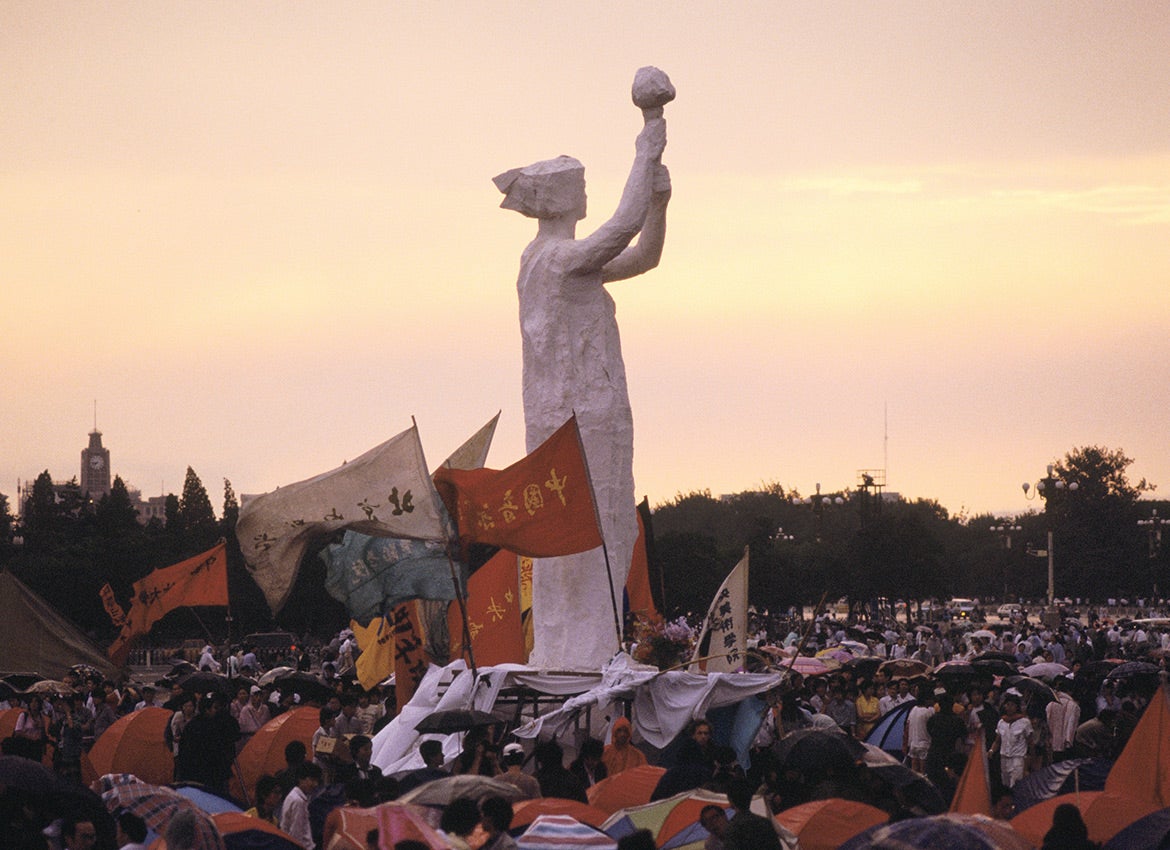

But reducing his role to that of a commentator on the CCP and the dissidence it has inspired does Link an injustice. He played a pro-democracy role in a significant episode of Chinese history, the spring 1989 Tiananmen Square tragedy.

In a series of events that could be storyboards in an espionage thriller, Link helped in the escape of the communist party’s “public enemy No. 1,” the dissident Fang Lizhi. In Link’s telling, he never intended any of it — he is an accidental dissident.

First Trips to China

Link’s first intersection with China was a Chinese-language course at Harvard University, which he entered in fall 1962, intending to major in physics. He took Chinese only because Tamil or Hindi courses were not available; he had spent part of his childhood in India. His first teacher of Chinese made an impression — in particular with her focus on Chinese tones — the subtle differences in inflection that differentiate between disparate words like “horse” and “mother.”

“Chinese is a tonal language in which a syllable’s meaning varies with voice pitch and contour,” Link said.

He connected with a sociology professor who offered a course in communist Chinese society, and the professor persuaded him to go to Hong Kong in 1966. After several more visits to Hong Kong, Link traveled to China for the first time in 1973 on a thank-you tour offered by the Chinese government for having served as an interpreter for a Chinese table tennis delegation the year before.

He would return to China as a language and literature instructor numerous times in the coming years, even as he left his Chinese-language professorship at Princeton University to teach at UCLA. By 1988, he was director of the Beijing office of the Committee on Scholarly Communication with the People’s Republic of China, an apolitical, private nonprofit organization of U.S. researchers under the U.S. National Academy of Sciences.

Meeting Fang Lizhi

In fall 1988, Link met Fang Lizhi at a reception. He had been warned by American colleagues to keep his distance from Fang, a Chinese astrophysicist whose liberal ideas helped inspire the pro-democracy student movement of the late 1980s. But Link waved off the admonitions, and the two soon became collaborators and friends.

On Jan. 7, 1989, Fang shared with Link a letter in which he asked Chinese premier Deng Xiaoping to grant amnesty to political dissidents. Such a gesture, Fang suggested in the letter, “would display a humanitarian spirit and promote a wholesome spirit in society.” The original letter was already in the mail, setting into motion the fateful pro-democracy movement that would soon come to a head. Fang had only one copy — handwritten — and no photocopier at home. Tucking the copy into Link’s hand, Fang asked him to translate the letter and share it with the scholarly world.

Chinese intellectuals took notice. Two months later, the poet Bei Dao organized an open petition of 33 prestigious Chinese “humanists” in support of Fang’s proposal. A second petition signed by 42 distinguished natural scientists appeared, and then a third, with 43 social scientists. In 2022, when veterans of the 1989 student movement created “An Exhibit on the Chinese People’s Heroic Struggle for Democracy” in Washington D.C., they featured Fang’s letter to Deng Xiaoping as a “precursor” of the historic 1989 student protests.

(Melirius via Wikimedia Commons)

A Barbecue Blockade

Soon after Link translated the letter, President George H.W. Bush arranged a “Texas-style barbecue” at the Great Wall Sheraton in Beijing. About 500 invitations were mailed, with Link and Fang among the invitees. Link asked Fang if he’d like a car ride to the reception, and Fang accepted. About five blocks from the hotel, two dozen plainclothes policemen swarmed their car, some carrying sidearms. One told them they had been speeding — an odd assertion given they had been frozen in rush-hour traffic.

The two men and their wives got out of the car to walk and were immediately intercepted and told they were not invited to the banquet. Fang was not a man easily deterred, and suggested to Link that they head to the U.S. Embassy to straighten out the matter. They hailed a taxi. Six blocks later, they were again stopped by armed police, who told the taxi driver he had a defective taillight.

Still undaunted, Fang suggested they take a bus. The first bus approached at a bus stop, slowed, then accelerated and drove past. When a second bus approached, it was flagged down — presumably by an agent of the CCP — about 100 yards short of the bus stop. The bus passed the stop. The foursome then decided to walk to the embassy.

“There were police in uniforms and in plainclothes on foot, and in the streets next to us on motorcycles and in cars,” Link would later recall in unpublished memoirs. “They clearly had ‘beats’ to cover. Sometimes, reaching the end of a block, one contingent would recede while another took over.”

When the party of four arrived at the embassy’s gate, a dozen police officers were waiting and told them no one was inside the building. It was a moot point by then, as the banquet at the Great Wall Sheraton had ended.

An Invitation to Tea

Pro-democracy/CCP tensions continued to rise in the spring of 1989. There were rumors of arrest lists and of CCP conversations about “the Fang Lizhi problem.” A question was posed to Link: Could Fang, his wife, and his son seek refuge at the U.S. Embassy? Link said he would ask friends attached to the embassy. The answer came back a couple days later: While they didn’t outright say no, embassy officials were short of enthusiastic.

June 3, 1989, Link and his wife went out to dinner and noticed military vehicles. “An odd pall hung over the city,” Link later wrote in his memoir, “but nothing that made me imagine that a massacre was imminent.” The following morning, his wife wakened him with the news that the massacre they had feared had happened, in and around Tiananmen Square, with at least several hundred protestors and bystanders killed.

By noon, Link traveled to check on Fang, his wife Li Shuxian, and their son. The family was on arrest lists, and friends were telling them to flee. But Fang refused to leave. Li Shuxian accompanied Link to the door.

“I told her that if she and Fang found anything that I could do to help, I was ready,” Link wrote years later. “She said, ‘Thank you. You can see Fang’s decision. But if there is anything, I will call and invite your children for tea.’”

The invitation to tea was code-speak. If Link received the tea invitation by phone — phones were almost certainly tapped — it meant the Fangs were ready to run. A few hours later, Link’s phone rang. Li Shuxian was inviting his children to tea.

Post-Tiananmen Escape

Link grabbed a cab, went to the Fangs’ apartment, and picked them up. His mind raced. It was a Sunday, and the embassy was closed. They detoured to the Shangri-la Hotel, where Link had friends from CBS News. Link rented a room for the Fangs and returned the next morning. By then, rumors swirled. The army was prepared to move on the Beijing University campus, and students were stockpiling weapons — bricks, rocks, whatever they could find. It was time to head to the embassy.

“Practical worries began popping to mind,” Link recalled. “We had our office car, but might we be tailed? Blocked? And if we did get to the (embassy) gate, how could we get in? Normally a guard was there. I would identify myself to him and say I need to see McKinney Russell (an embassy official). He would call in, get permission, and let me through. How would I get the three Fangs through?”

He developed a plan. A CBS News friend would go with them.

“I would approach the guard as usual and, after the gate was open, signal to (the CBS friend) to lead the Fangs through while I stood physically to prevent the gate from closing,” he said.

To their surprise, they reached the embassy without incident. Their luck continued at the embassy gate, where two young soldiers armed with machine guns “seemed almost bored” as they let them in without even asking questions. The acting ambassador received them, but the reception was unenthusiastic. Link and the Fangs again went to a hotel.

But a few hours later, the embassy’s posture had shifted dramatically. The ambassador visited the Fangs to say they should return to the embassy to stay as long as they wanted “as the personal guests of President Bush.” Later, Link would learn that Washington was horrified to learn Fang had been turned away at the embassy.

“Washington’s pressing concern was not to protect a courageous human being or to express political support for Chinese free-thinking,” Link wrote. “It was American politics: What if something bad happened to Fang? What would voters think of an administration that put a famous Chinese dissident in jeopardy?”

The Fangs were delivered to an underground apartment in the U.S. ambassador’s residence and would eventually make their way to the U.S., where Fang lived the rest of his life as an expatriate. He died in 2012.

The Chinese farmers’ proverb sizhu bupa kaishui (死猪不怕开水烫) tang translates to: ‘Dead pigs aren’t afraid of hot water.’

“We blacklisted dead pigs not only enjoy maximal free speech but can use it to assist others. Journalists like to call us for our opinions. We may or may not have good analyses, but at least the journalist knows we will not be needing to equivocate.” — Perry Link

Blacklisted, Silently

It would be several years before Link’s “China troubles” became evident. In 1989, he returned to Princeton when a Chinese literature position opened. From 1989 to 1995, he made six visits to China, including for his work with the Princeton-in-Beijing language program based at Beijing Normal University, which stressed speaking Chinese in proper tones. But in 1996, fresh visa in hand, Link was stopped at the Beijing airport and turned back, with a stern, uniformed man declaring: “We have checked with our superiors, and you are not welcome in our country.”

He would subsequently become known for his 2001 English-language translation of “The Tiananmen Papers.” The book is a damning account of the Chinese Communist Party’s culpability in the Tiananmen Square massacre, transcribed from party leaders’ own words. Many assume Link’s blacklisting is on account of that work. But his travel trouble started years before.

“It was then that I had crossed a line between just saying things and actually doing them,” he wrote, referring to the Fang episode in 1989. But, being blacklisted has an upside.

“Blacklisting leaves a person freer than before. This is because once a blacklisting happens, the fear that it might happen suddenly disappears. It is the fear of blacklisting — not the blacklisting itself — that causes people to self-censor,” he said. “When the pressure to self-censor disappears, it becomes much easier to say exactly what one thinks. The sense of release was palpable, invigorating.”

An expression representing this principle is the Chinese farmers’ proverb sizhu bupa kaishui tang (死猪不怕开水烫), which translates to: ‘Dead pigs aren’t afraid of hot water.’

“We blacklisted dead pigs not only enjoy maximal free speech but can use it to assist others,” Link said. “Journalists like to call us for our opinions. We may or may not have good analyses, but at least the journalist knows we will not be needing to equivocate.”

A “Chuanqi Story”

Today, Link will tell you the Princeton-in-Beijing program is his greatest professional achievement. Speaking Chinese in correct tones, and teaching others to, is a passion.

“If you talk to him on the phone without seeing him, it would be very difficult to tell he is not a native speaker. Not only a native speaker, but a well-educated native speaker,” said Chih-p’ing Chou, who met Link in 1977 and created with Link the Princeton-in-Beijing program in the early 1990s; the two taught the program together until Link was blacklisted.

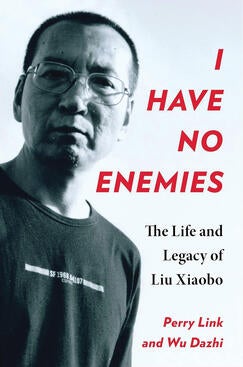

Link, who joined the UCR faculty in 2008, is a leading authority on modern and contemporary Chinese culture. He is approaching 80 years old and still teaches a full course load at UCR, where he is the Chancellorial Chair for Teaching Across Disciplines. He has published numerous books — including his latest, the meticulously researched, critically acclaimed 2023 biography “I Have No Enemies: The Life and Legacy of Liu Xiaobo,” published by Columbia University Press.

(UCR/Stan Lim)

“I have had, roughly speaking, three related careers — in language teaching, in literature, and in dissident politics,” Link wrote in his memoirs, still a work in progress. “I am best known for the third, but in my own view, have performed best in the first.”

He considers those dramatic episodes of his life a “chuanqi story” — a strange story: “I have felt that they have arisen from my environments outside, not my initiatives inside.”

When he stood on a cold Beijing street with Fang that dark day in June, he could have left his friend.

“But the thought did not even occur. There is nothing to ‘weigh’ about it. A primal sameness took over,” he said. “I feel embarrassed when people say, ‘You were so courageous to help Fang Lizhi on the day of the massacre.’ The events of that day stunned me into a state of mind where decisions were neither courageous nor cowardly, but reflexive. ‘We need a ride; can you help?’ ‘I think so; let me try.’ It was as simple as that.”

His colleague and friend Orville Schell attributes Link’s characterization of the Fang episode to his being “a very understated and nonpromotional person who doesn’t want to be grandiose.” Schell said Link assumed a risk that — for a China scholar — is greater even than the stuff of police tails and arrest lists.

The peril for him was what ultimately happened; he got kicked out,” said Schell, a China expert and former UC Berkeley dean who first met Link at a meeting of the Committee on Scholarly Communications in the early 1980s; years later, he wrote the introduction to Link’s “The Tiananmen Papers.” “It’s a huge loss. He risked (his access) and he lost it.”

After almost 30 years away, Link longs to return to China.

“I miss Chinese life on the ground: The sounds, sights, and smells of the streets; the charming snacks that can be had there; and the lively, authentic speech of ordinary people,” he said.

But he is caught in a paradox. He never intended to engage in activity that would get him blacklisted. But he doesn’t want to do what he would have to do to get off the blacklist — praise the CCP and retract his criticisms. It evokes a 2002 passage Link wrote in The New York Review of Books, in which he likened the Chinese Community Party and its censorship to a giant anaconda.

“Normally the great snake doesn’t move,” he wrote. “It doesn’t have to.”