A team of researchers at the University of California, Riverside, seeking to upend a long-held theory explaining how hormones freely enter and exit cells, has received a major boost in the form of a $1 million award from the W. M. Keck Foundation.

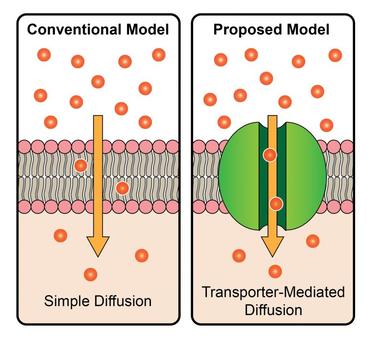

Steroid hormones — chemical messengers derived from cholesterol in the body — regulate immune response, sexual maturation, cancer progression, metabolism, and inflammation. Despite their importance, little is known about how they cross cell membranes. Researchers in the field have long believed that diffusion explains the process.

Challenging this dogma, the UC Riverside researchers posit that membrane transporters are involved, facilitating the transport of steroid hormones across cell membranes, akin to an airport jetway guiding passengers from a terminal into an airplane.

Importers are transporters that allow material into the cell. The Keck Foundation grant will allow the researchers to characterize the transporter Ecdysone Importer (EcI) in the fruit fly, a model organism, and also to identify and characterize similar transporters in mammals using mouse models and human cells.

If successful, the UCR research, which impacts processes from pest control to cancer, would be the first to show the function and significance of a steroid hormone importer in vivo in any organism. It would facilitate the development of drugs that are more specific and less likely to result in resistance.

Transporters similar to EcI exist in all animals, including humans. Largely responsible for uptake of drugs, they can be detected at many blood–tissue interfaces and have the potential to be functionally highly specific.

“We hypothesize that mammalian steroid hormones need EcI-like transporters to enter cells,” said Sachiko Haga-Yamanaka, an assistant professor of molecular, cell, and systems biology, and the principal investigator of the three-year grant. “These transporters would be ideal targets for drugs aimed at controlling steroid hormone transport. We expect the successful completion of our project will show that steroid hormones do not enter cells by simple diffusion, but rather via transporters lodged like revolving doors within the cell membrane. This would overturn a long-standing paradigm in endocrinology that steroid hormones are imported into cells only by simple diffusion.”

Steroid hormones are secreted by the adrenal cortex, testes, and ovaries, and by the placenta during pregnancy. They help balance salt and water in the body and play a role in how well the body withstands illness and injury. Soluble in lipids (fats), they can pass through the cell membrane of target cells to some degree unaided, but the UCR team has now found that for the most efficient uptake transporters may be required.

Haga-Yamanaka will be joined in the project by co-principal investigators Naoki Yamanaka, an assistant professor of entomology and an expert on steroid hormone signaling in insects; and Frances Sladek, a professor of cell biology and an expert on mammalian nuclear receptor signaling and cancer biology. Besides working to confirm steroid hormones require membrane transporters to enter cells in vivo, the triad will attempt to show that chemical reagents can manipulate how the transporters function — knowledge that is especially useful for drug development.

To show that EcI-like transporters play a crucial role in steroid uptake in mammals, the researchers will work on mice as well as human cell lines, and focus their attention on glucocorticoids, a group of steroid hormones produced during stress by the adrenal gland.

“We expect our work will show for the first time that membrane transporters serve as efficient conduits in mammalian cells, facilitating the entry of steroid hormones in their target tissues,” said Yamanaka, whose lab first identified EcI. “In preliminary studies on the fruit fly, we found transporters that can transport ecdysone in vitro and in vivo. Further research on mice and human cells will show that distinct EcI-like transporters regulate steroid hormone entry into different tissues, and that this uptake can be manipulated. Not only would this dramatically change our fundamental understanding of how steroid hormones function, but it also could lead to a new class of drugs and pest control reagents.”

The generous Keck award will allow Haga-Yamanaka, Yamanaka, and Sladek to screen a library of natural and synthetic chemicals that either facilitate or inhibit how transporters function. After shortlisting candidate chemicals, they will test them in vivo to identify reagents for manipulating steroid hormone uptake and function in a tissue-specific manner.

“This exercise will most likely help identify a novel class of drugs to regulate a number of pathological processes that steroid hormones control,” Sladek said. “We are confident the results from our cross-species research will pave the way for identifying chemical reagents that can both block ecdysone uptake and control insect pests and disease vectors, as well as assist in the development of drugs for modifying the uptake of specific steroid hormones in humans.”

Following this project, the researchers plan to examine if the EcI-like transporters can also transport mammalian steroid hormones such as estrogens, androgens, and progestogens. The significance of the transporters in hormone-dependent cancers will also be explored.

Based in Los Angeles, the W. M. Keck Foundation was established in 1954 by the late W. M. Keck, founder of the Superior Oil Company. The foundation’s grant making is focused primarily on pioneering efforts in the areas of medical, science and engineering research. The foundation also maintains an undergraduate education program that promotes distinctive learning and research experiences for students in the sciences and in the liberal arts, and a Southern California Grant Program that provides support for the Los Angeles community, with a special emphasis on children and youth from low-income families, special needs populations and safety-net services. For more information, please visit www.wmkeck.org.