The race is on to find manufacturing techniques capable of arranging molecular and nanoscale objects with precision.

Engineers at the University of California, Riverside, have altered a virus to arrange gold atoms into spheroids measuring a few nanometers in diameter. The finding could make production of some electronic components cheaper, easier, and faster.

“Nature has been assembling complex, highly organized nanostructures for millennia with precision and specificity far superior to the most advanced technological approaches,” said Elaine Haberer, a professor of electrical and computer engineering in UCR’s Marlan and Rosemary Bourns College of Engineering and senior author of the paper describing the breakthrough. “By understanding and harnessing these capabilities, this extraordinary nanoscale precision can be used to tailor and build highly advanced materials with previously unattainable performance.”

Viruses exist in a multitude of shapes and contain a wide range of receptors that bind to molecules. Genetically modifying the receptors to bind to ions of metals used in electronics causes these ions to “stick” to the virus, creating an object of the same size and shape. This procedure has been used to produce nanostructures used in battery electrodes, supercapacitors, sensors, biomedical tools, photocatalytic materials, and photovoltaics.

The virus’ natural shape has limited the range of possible metal shapes. Most viruses can change volume under different scenarios, but resist the dramatic alterations to their basic architecture that would permit other forms.

The M13 bacteriophage, however, is more flexible. Bacteriophages are a type of virus that infects bacteria, in this case, gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, which is ubiquitous in the digestive tracts of humans and animals. M13 bacteriophages genetically modified to bind with gold are usually used to form long, golden nanowires.

Studies of the infection process of the M13 bacteriophage have shown the virus can be converted to a spheroid upon interaction with water and chloroform. Yet, until now, the M13 spheroid has been completely unexplored as a nanomaterial template.

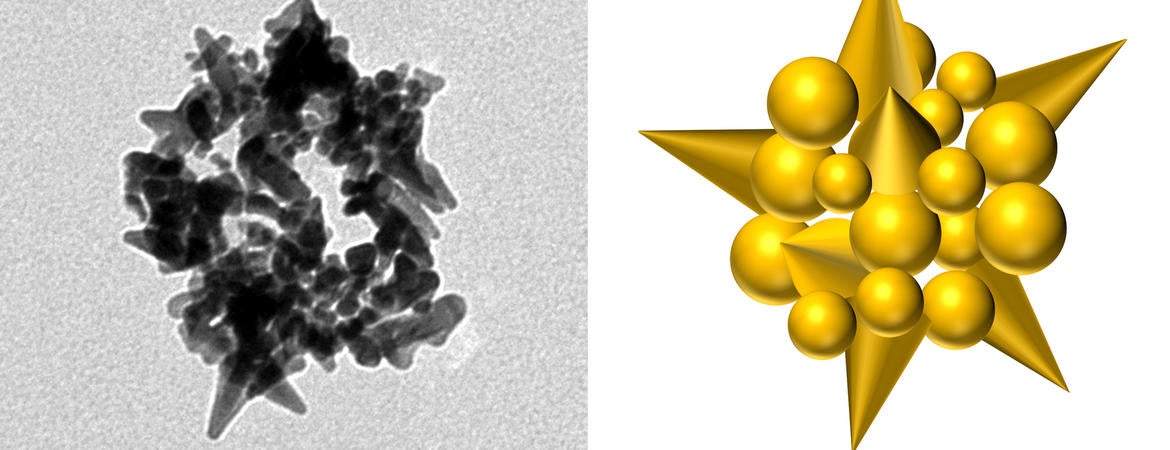

Haberer’s group added a gold ion solution to M13 spheroids, creating gold nanobeads that are spiky and hollow.

“The novelty of our work lies in the optimization and demonstration of a viral template, which overcomes the geometric constraints associated with most other viruses,” Haberer said. “We used a simple conversion process to make the M13 virus synthesize inorganic spherical nanoshells tens of nanometers in diameter, as well as nanowires nearly 1 micron in length.”

The researchers are using the gold nanobeads to remove pollutants from wastewater through enhanced photocatalytic behavior.

The work enhances the utility of the M13 bacteriophage as a scaffold for nanomaterial synthesis. The researchers believe the M13 bacteriophage template transformation scheme described in the paper can be extended to related bacteriophages.

The paper, “M13 bacteriophage spheroids as scaffolds for directed synthesis of spiky gold nanostructures,” was published in the July 21 issue of Nanoscale. Other authors, all based at UCR, include Tam-Triet Ngo-Duc, a doctoral student in materials science and engineering; Joshua M. Plank, a doctoral student in electrical and computer engineering; Gongde Chen, a doctoral student in chemical and environmental engineering; Reed E. S. Harrison, a doctoral student in bioengineering; Dimitrios Morikis, a professor of bioengineering; and Haizhou Liu, a professor of chemical and environmental engineering.

The project is supported by award number N00014-14-1-0799 from the U.S. Office of Naval Research.