Computer scientists at the University of California, Riverside, have discovered a vulnerability in all modern Wi-Fi routers that cannot be fixed.

Associate Professor Zhiyun Qian and doctoral student Weiteng Chen, both from UCR’s Marlan and Rosemary Bourns College of Engineering, describe an exploit that takes advantage of the interaction of two internet universal protocols: transmission control protocol, or TCP, and Wi-Fi. The exploit does not target any traditional security vulnerability. Instead, the security weakness lies in a fundamental Wi-Fi design decision made over 20 years ago that is extremely difficult to change.

TCP has been around since the internet was invented and virtually all websites use it. TCP breaks information into manageable chunks that can be transmitted between computers over the internet. Each chunk, known as a “packet,” receives a number within a sequence unique to that particular communication that ensures it is delivered correctly. The first number of the initial sequence is randomly chosen, but the next numbers will increase predictably, so the receiving computer can arrange them properly if they arrive out of order.

For example, when you click to enlarge an image on a website, your computer asks the remote computer to send the image data. The remote computer breaks the data for the image into numbered packets and sends them over the fastest routes. Your computer replies to acknowledge each packet and assembles them in correct order to display the image on the screen.

In order for an attacker to intercept this communication, they have to pretend to be the sender and correctly guess the next number in the sequence. Because there are about 4 billion possible sequence numbers, it’s nearly impossible to guess successfully before the communication completes.

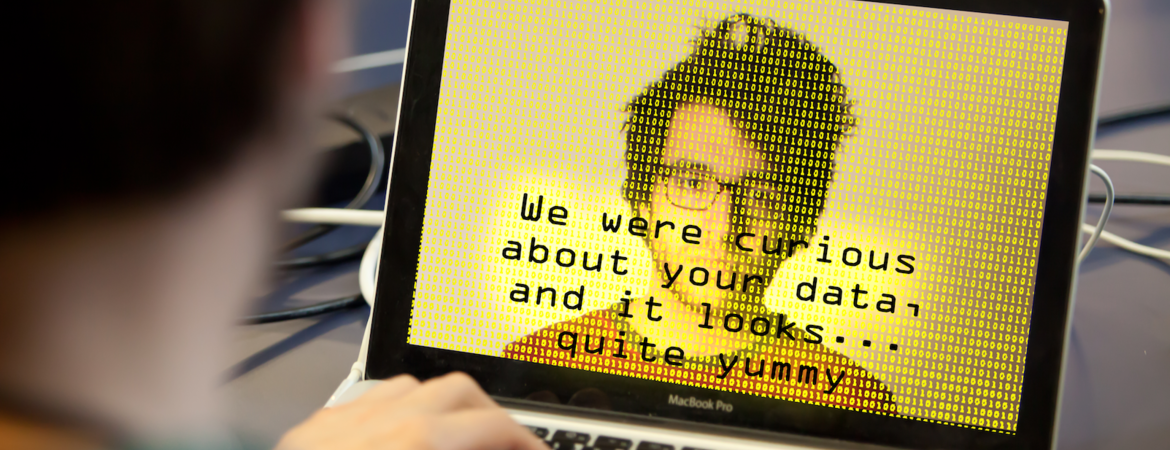

But if the attacker can figure out which number triggers a response from the recipient, they can figure out the rough range of the correct number and send a malicious payload pretending that it comes from the original sender. When your computer reassembles the packets, you’ll see whatever the attacker wants.

How does the attacker figure out which number triggers a response?

Wireless routers can only transmit data in one direction at a time because they communicate with devices in their network on a single channel. Like walkie-talkies, if both parties send information at the same time, there will be interference. This is known as a half-duplex transmission, a characteristic of all wireless routers.

The unidirectional nature of half-duplex wireless means there is always a time gap between a request and a response. If an attacker sends a spoofed TCP packet with a guessed sequence number, followed by a regular packet of its own and an immediate response, they know they are wrong because in a half-duplex system it should take longer for the recipient to reply to the spoofed packet. If it takes longer, they know they have guessed the sequence correctly and can hijack the communication.

To be contacted by a remote attacker, the victim has to visit a site controlled by the attacker, who is not necessarily nearby or connected to the same Wi-Fi network. The website executes a JavaScript that creates a TCP connection to a banking website, or another chosen by the attacker. The victim is not aware that the connection has been established. In their experiments, the researchers found that the victim needs to stay on the malicious website for only one to two minutes for the attack to succeed.

“You can imagine a website that displays pirated content such as movies, NBA games, or video games, which lure the user to stay for a sufficient period of time,” said Qian.

In the meantime, the remote attacker guesses the sequence number of the banking connection. Once the attacker knows the correct sequence number, they can inject their own copy of the banking webpage into the browser cache — a tactic known as web cache poisoning, which can steal passwords or other sensitive information.

The next time the victim visits the banking website, they will see the malicious copy cached in the browser. The attack may not steal things immediately, but the trap has been loaded.

“Whenever the victim visits the banking site in the future, they will always see the malicious version as it is already stored in the browser and won’t expire for tens of years, or until the victim clears their cache,” said Qian.

This poisoning will not work on encrypted websites that use HTTPS and HSTS, nor will it work on Ethernet connections.

However, some bank websites, especially outside the U.S., use HTTP for their home pages and only direct the user to an HTTPS page when they click to sign in. In a series of videos, the authors demonstrate how easy it is for the attacker to insert a fake login area on the home page to capture the user’s credentials.

Many websites do not use encryption, and the exploit described by Chen and Qian could be used to help spread fake news in addition to stealing private data. It could also be used for espionage or to interfere with critical activities that might be managed via wireless internet.

Don’t expect a fix for this security flaw anytime soon. The only solution is to build routers that operate on different frequencies for transmitting and receiving data. When the researchers presented their findings to the committee responsible for creating the wireless technology, its members said new technology is at least five years away.

The paper, “Off-Path TCP Exploit: How Wireless Routers Can Jeopardize Your Secrets,” was presented at the Usenix Security Symposium in August.

(photo credit: ITSVeronica on Wikimedia Commons)