There is a whole new dynamic that pundits, campaign managers, and voters will be negotiating in American politics, and the starting gun has already been fired.

That is, the complicated — so says the research — dynamic of how voters regard multiracial candidates. On the national stage, it began with Barack Obama, and continues in this election cycle with Democratic nominee Joe Biden’s running mate, California U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris.

The research of a 2017 UC Riverside doctoral graduate sheds light on a 2020 election historic in that the first biracial woman is running for vice president. Danielle Lemi is writing a book, sharing what researchers know about how voters respond to multiracial candidates.

Multiracial identification is a relatively new field of study in political science.

“We have not had much of history to go by, at least for the office of president and vice president,” said Augustine Kposowa, a UCR professor of sociology, who conducted the research with Lemi that provided background for her findings. Among their publications is the article, "Are Asian Americans who have Interracial Relationships Politically Distinct?" published in 2017 in DuBois Review.

U.S. Census data indicates people of two or more races are among the fastest-growing groups in the U.S. today, estimating about 7% of the adult population is multiracial. And the demographic is growing three times faster than the rest of the population. By 2060, the Census Bureau predicts the multiracial population will have tripled.

Research has established that voters align with candidates from their own race. But there’s little research on the support multiracial candidates may expect relative to candidates who identify as one race.

Does a Black voter align with Kamala Harris as fully as the voter would support a monoracial candidate? How about a voter of Asian American heritage — the other identifier of Harris’s race?

Lemi said some white voters didn’t give Barack Obama credit for having a white mother, exposing him to the same racial epithets a monoracial Black candidate might expect. And, Lemi argues, some voters want multiracial candidates to pass a litmus test. That is, “Do you act like one of us?”

The multiracial candidate’s identity can spin to his or her advantage, too. Multiracial candidates may be branded as “exotic” or “attractive,” and preferable to monoracial candidates. Drilling down further, research shows lighter-skinned candidates benefit to a greater extent from this dynamic. Black-white candidates are attractive to all voters, Lemi said, and positioned to be “bridge builders” — call it “The Obama Effect.”

“Multiracial candidates may enjoy an advantage when appealing to voters completely outside of their race,” Lemi wrote in her summer 2020 paper, “Do Voters Prefer Just Any Descriptive Representative? The Case of Multiracial Candidates," published in Perspective on Politics.

In her paper, Lemi — now a fellow at Southern Methodist University’s Tower Center — looked at research on voter responses to multiracial candidates. Lemi surveyed white, Black, Asian, and Hispanic respondents, with the sample leaning Democratic, liberal, and relatively young. Among the participants were 190 white, 203 Black, 186 Hispanic, and 206 Asian or Pacific Islander would-be voters.

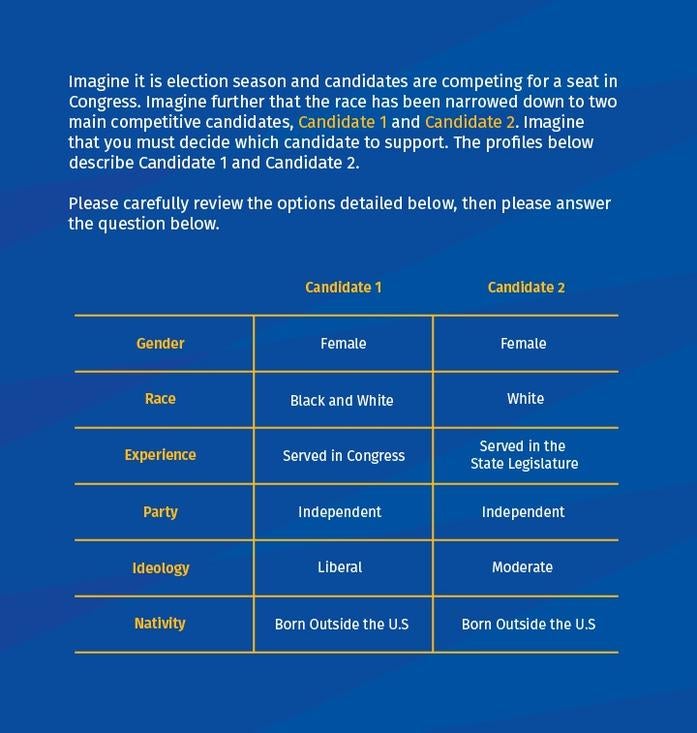

Ten pairs of faux candidates — complete with candidate profiles — were developed, with racial classification assigned randomly. Some of the phantom candidates were monoracial, and some were multiracial. Candidates were assigned certain attributes correlated with race, gender, and party affiliation. For example, candidates of color tended to be more liberal and have less political experience due to underrepresentation in political institutions.

The below image demonstrates the choices study participants faced:

Consistently, the respondents voted for the candidates of their race over candidates of another race, or multiple other races.

But how would — for instance — white voters react to a candidate who is half-white, and half another race? The study found they were 3-7 percentage points less likely to vote for a multiracial white candidate than for monoracial white candidate.

Lemi’s research also found that multiracial candidates outside of someone’s race were more likely by about 3 percentage points to be selected than outside monoracial candidates. That is to say, a white voter was about 4 percentage points more likely to select a Black-Asian candidate than an "outside" monoracial candidate.

The dynamics are particularly tricky with Harris.

Consider Harris’s 2016 U.S. Senate race, against a Latino woman. An analysis of data from the 2016 National Asian American Survey showed Asians were more likely to vote for Harris when they knew she was Asian. Karthick Ramakrishnan, a UCR professor of political science and public policy who directed that survey, said Asian American voters are also more likely to vote generally when there is an Asian American on the ballot.

"Our past research has shown that Asian Americans, and especially Indian Americans, were much more familiar with Kamala Harris even before she ran for president, and had a favorable impression of her," said Ramakrishnan, who leads the National Asian American Survey and founded AAPIData.com, which publishes demographic data and policy research on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

But when Black Californians in 2016 were told Harris also has Asian heritage, respondents who declared their racial identities to be important indicated they were less likely to vote for her than if only told she is Black. And so, better for Harris that Black voters view her as Black, rather than Black and Indian.

“It indicates that Black Californians with strong racial identities punish Harris when she is framed as multiracial,” Lemi wrote in her summer 2020 paper. The reason, Lemi surmises, is because those Black voters in the sample may question whether Harris adheres to norms of group identity.

Lemi’s research also found voters ally themselves with multiracial candidates based on perceived commonality with their own race group. For example, a Black voter is more likely to cast a ballot for a Black-Hispanic candidate than for a Black-Asian candidate. Kposowa said this is likely a product of what Black voters consider “a continuation of U.S. racial hierarchy: whites at the top, Asians next, Latinos next, and Blacks at the very bottom.”

As a footnote to her research, Lemi broaches a popular sentiment: Race will be less prescient as more people become multiracial. Lemi’s research suggests, contrary to that sentiment, that more racial categories could lead to more complicated dynamics. That is, identity boundaries may harden.

“As the growing multiracial population comes of age and runs for office, multiracial candidates may encounter challenges to using their backgrounds strategically to secure their racial constituencies. Ultimately, those challenges may come from members of their own groups,” Lemi concluded.