During the first century of American colonization, as many as 20 million people in Mexico perished from disease, violence, and exploitation. Jennifer Scheper Hughes, a professor in the Department of History at the University of California, Riverside, examines this period from historical and theological perspectives in her new book, “The Church of the Dead: The Epidemic of 1576 and the Birth of Christianity in the Americas.”

In 1576, a catastrophic epidemic claimed almost 2 million lives and simultaneously left the colonial church in ruins. In the crisis and its aftermath, Spanish missionaries and surviving Indigenous communities asserted radically different visions for the future of Christianity.

“Thinking about the church in Mexico is important,” Hughes said. “It predates by a century the arrival of the Puritans to New England. Mexican Catholicism is the oldest form of Christianity in the hemisphere.”

When Hughes began her research in Spanish and Mexican archives 10 years ago, she did not imagine the work would come to completion in the midst of a global pandemic.

“Epidemics have often been the cause of tectonic social and cultural shifts as people struggle to rebuild and reconstitute societies in their wake,” Hughes said. “Human cultures transfigure and transform in the effort to survive epidemic cataclysms. Even in the face of loss and destruction, survivors are sometimes able to leverage the disruption to build something powerful and new.”

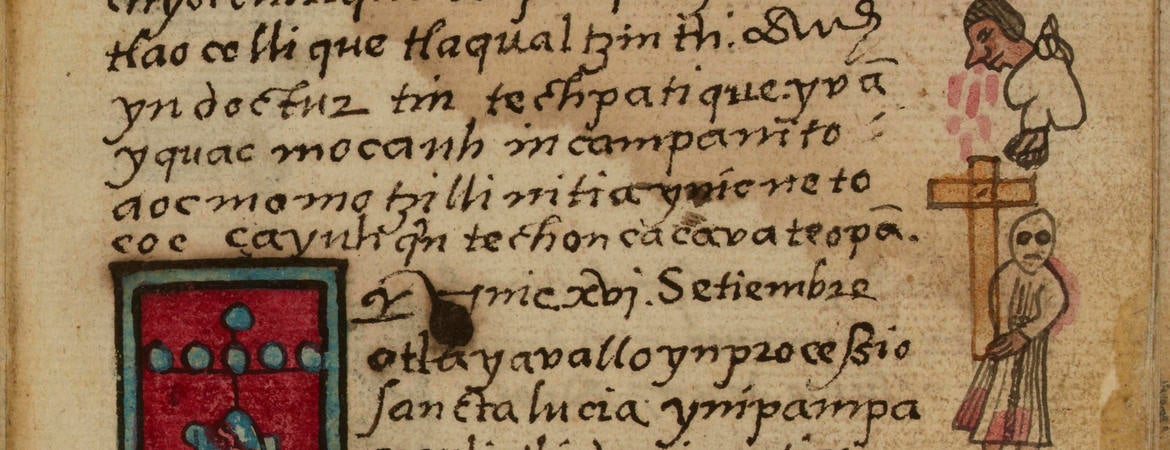

Using archival records and correspondence from missionaries in the Americas, Hughes illuminates how early leadership of the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico maneuvered to establish a foothold for evangelizing the Indigenous population. She also consults materials authored by colonial era Nahua, Mixtec, and Maya Catholic communities as they sought to shape colonial realities in their interests.

During the 1576 outbreak, Spanish missionary friars transformed themselves into frontline medics and nurses. Providing medical care for the sick became for them a sort of religious sacrament, like the Eucharist. At the same time, Native Mexican communities founded their own hospitals and clinics. Here they organized care for the sick with some autonomy from Spanish authority.

Perhaps the most important conclusion of Hughes’ research is that after the epidemic, surviving communities of Indigenous Catholics asserted an alternative, rival vision for the church. Their vision transformed the future of Christian practice in Mexico so that it upheld fundamental Mesoamerican beliefs and institutions. The colonial church was compelled to yield to this purpose.

“It was a labor of a century to take this imposed religion and forge it into something they recognized as sacred,” Hughes said. “They preserved some received Christian ideas and practices that were recognizable and resonant and rejected others that they found to be broken, compromised, incoherent, or irredeemable.”

According to Hughes, there are common misunderstandings that circulate about the origins of American Christianity that are not necessarily upheld by historical evidence. One of these is that the project of Christian empire in the Americas was inevitable, destined to succeed by missionary fervor or by the sheer violent force of colonial imposition. In retrospect, Christianity’s global spread in these centuries can appear to be almost viral. Yet Spanish observers frequently perceived American Christianity as perpetually on the brink of failure and collapse.

“Christianity spread in spite of these diseases and not because of them,” Hughes said. “People often assume Christianity gave hope or comfort in the midst of crisis or provided a religious explanation for catastrophic disease in the absence of a scientific one.”

In Mexico, epidemics were seen as one of the greatest threats to the survival of the church. The rapid and devastating loss of life starved the church of potential members and left missionaries in despair.

In strategic deliberation, surviving communities of Indigenous Christians in Mexico leveraged the church to defend and protect community integrity and autonomy, preserving some of the most valued structures of Mesoamerican society for future generations.

According to Hughes, Mexican Christianity today is the legacy of Indigenous Catholic survivors of the 16th century cataclysm. In the midst of the crisis, it wasn’t just that people were trying to pick up the pieces. They were actively working to assert and implement a vision for the future. She likens this rebuilding to the aftermath of the current pandemic.

“Today, we are beginning the process of rebuilding from the COVID-19 pandemic, and there is an opportunity to renegotiate the principles of our society toward more just relationships and more humane social institutions,” Hughes said. “We can be attentive and attuned to this opportunity. Human cultures have evolved to be resilient to catastrophes such as this.”

“The Church of the Dead: The Epidemic of 1576 and the Birth of Christianity in the Americas” is available online and in print on Aug. 3 from New York University Press.