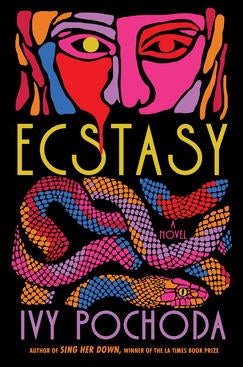

We’d like to think that gender relations have improved significantly in the last 2,600 years, but Ivy Pochoda’s new book “Ecstasy” shows how some forms of oppression have stood the test of time. A modern retelling of the Greek tragedy “The Bacchae,” the book shines light on the cages we build for ourselves — women in particular.

Known for her crime novels such as LA Times Book Prize winner “Sing Her Down,” horror is a new genre for Pochoda, a visiting assistant professor with UCR’s Palm Desert Low-Residency MFA program. As she told The New York Times’ Book Review, horror lends itself particularly well to illuminating gender inequality.

“The imbalance starts to eat away at your sense of self, personally and professionally,” she told The New York Times. “There’s still this institutionalizing of certain roles for women. There’s a rage about that. Horror gets people to pay attention.”

In “Ecstasy,” Pochoda examines how wealth can draw men and women toward traditional gender roles. While studying literature and ancient Greek at Harvard, Pochoda met women who slipped into roles as housewives after graduation, despite their Ivy League degrees.

“I wanted to show how we overlook the way a woman who might have everything actually is still being oppressed,” said Pochoda. “I wanted to talk about systemic oppression, how some of the structures of marriage are still sort of patriarchal.”

“Ecstasy” follows Lena, a former ballerina who gave up dance to marry rich, as she pulls away from her life of luxury.

Like Euripides’ original play, the book is set in Naxos, Greece, a place Pochoda knows well from researching “Epoca,” a steampunk fantasy series she collaborated on with NBA great Kobe Bryant.

Lena arrives on the island with her son, Drew, his wife, and a friend from her ballerina days. Drew has taken over his recently deceased father’s business and is about to open a luxury resort on the island. While most would envy Lena’s lavish suite, she finds it stifling, and is instead drawn to a group of revelers on the beach below that her son is attempting to remove before the hotel opens.

“I think that luxury is a prison that people would love to have,” said Pochoda, “but I do think there's a really dark side to it where you sort of lose your sense of self and identity.”

Throughout the book, Drew attempts to dictate where his mother and his wife go, how they look, when they eat and sleep.

“I'm interested in the fact that sometimes people who are very privileged, who are very educated, still don’t really see women as equals,” she said.

Yet the book also makes clear that if luxury is a prison, it’s one that people build for themselves. Lena made the choices that brought her to this life, including the choice to allow her late husband to make decisions for her.

As Lena steps away from her high-class world, she trades one form of control for another. In prose that feels like a melody, Pochoda weaves a haunting narrative of how the DJ and drug dealer, who preside over the women on the beach, exert their own power over the revelers.

Even Luz, the drug dealer and a manipulator in her own right, describes how the DJ – the book’s stand-in for the god Dionysus from the original play – uses his charisma and stage presence to exert an almost supernatural control over the revelers.

“It wasn’t just his music. It was him,” thinks Luz. “He trapped me in threads of noise, luring me down darker corridors until I knew – I knew – I would never escape.”

“I danced until there was no me. Only him.”

Growing up in the ‘90s, Pochoda got to know the New York club scene, and then the electronic dance music — EDM — festival circuit while living in Amsterdam.

“A really good DJ can summon this feeling of abandon or heightened emotion,” said Pochoda. “A drug dealer can do the same thing. Then marriage is another way of signing up for manipulation because you might have to allow them to make decisions for you."

As it illustrates the sacrifices people make to live in luxury, “Ecstasy” also shows just how dangerous truly letting loose can be, particularly through Drew’s perspective.

“He's an asshole, but he's not entirely wrong,” said Pochoda. “There's a dark side to being free on the beach, to letting your freak flag fly.”

“Sometimes you go too far and can't come back.”