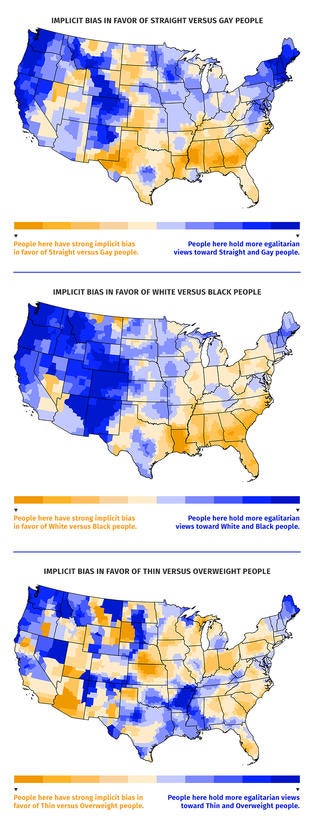

A series of maps created by a UCR professor highlights hot spots for intergroup bias across the nation. The researchers aggregated data to determine the regions where implicit and explicit bias are greatest related to race, weight, and sexual preference.

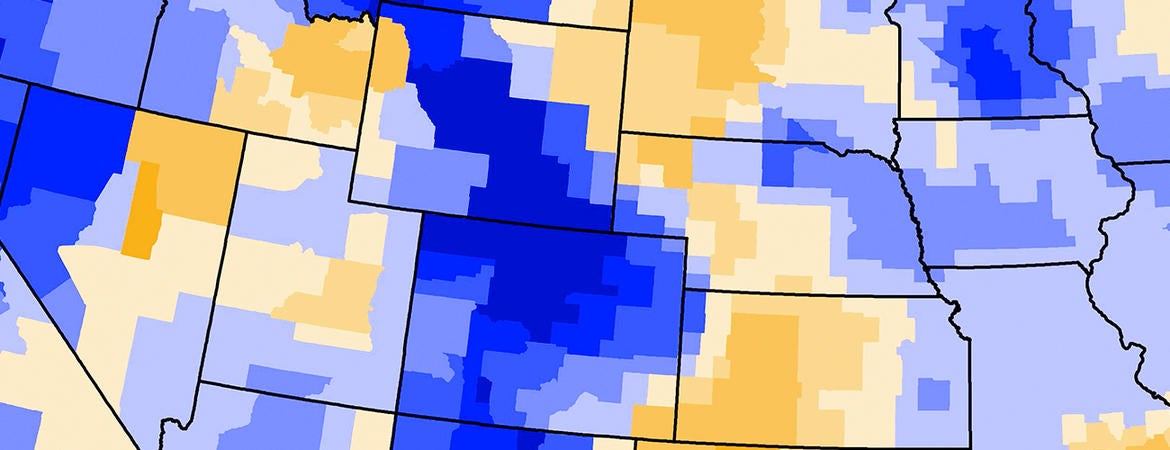

The maps range from deep blue, which represents places in America with the most egalitarian views, to deep orange, which represents places with the most biased views. For instance, the Northwest is deep blue – egalitarian – on race and sexual preference. Conversely, deep orange stretches across Southern states, representing biases in favor of white over Black people, and in favor of straight over gay people.

One of the most revelatory features of the maps is what’s not there.

“The maps don’t have a conceptual opposite to the orange regions because that would indicate bias in favor of lower-status groups (Black, gay, and overweight people), and that doesn’t really exist in America,” said Jimmy Calanchini, a UC Riverside researcher who led the study. “There aren’t really any regions of America that are extremely biased against higher-status groups.”

The maps measure two kinds of bias: explicit and implicit. Explicit bias is the bias people report directly, in response to questions like “How positively do you feel about this group of people?” Implicit bias is bias that people may be unwilling to report, but still influences their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

The maps reveal that the Southeastern U.S. holds implicit and explicit bias in favor of white vs. Black people, and straight vs. gay people, while much of the Northeast, Rockies, and the western states are more egalitarian in their views toward both populations.

Other findings: the Northeast and West Coast hold deep bias in favor of thin vs. overweight people, but parts of the South, Southeast, and Rockies are more egalitarian in their views towards weight.

“Everybody loves the groups on top in society – the pretty people and the powerful people,” Calanchini said. “They are the heroes in our movies, the leaders in our communities, and on the covers of our magazines. Consequently, people who are members of those high-status groups love themselves. However, people who are members of lower-status groups are also often biased in favor of higher-status groups, too, because they grew up in America, watching the same movies and immersed in the same culture. That’s why it’s hard to find regions with large numbers of people biased against high-status groups.”

When contrasting the implicit vs. explicit maps, the blue and orange coloring is similar. But there are some notable variances in the bias people express (explicit) vs. the bias they unwittingly feel (implicit).

For example, while Florida is egalitarian in explicit bias toward gay vs. straight people, the state’s implicit bias favors straight people.

The analysis found regional explicit and implicit race biases are likely to correlate: places with strong implicit racial biases also have strong explicit racial biases. They found the same thing with sexuality bias: places with strong implicit sexuality biases also have strong explicit sexuality biases. In contrast, regional implicit and explicit biases are much less related in the domains of disability, age, and weight.

The bias maps are part of a far-reaching study just accepted for publication in the journal Advances in Experimental Social Psychology that includes the broadest analysis to date of existing regional bias research. It considered 32 studies involving more than six million people.

The vast majority of the data analyzed for this publication come from internet volunteers, and focused only on the United States, but Calanchini stressed that the future studies must consider other people’s responses.

“In order for regional intergroup bias research to continue to advance, it cannot be based so heavily on a single data source,” Calanchini said. “Such disproportionate dependence on one data source… limits the external validity of existing regional intergroup bias research.”

Of the colored maps, Calanchini said: “It doesn’t mean everyone in Alabama is racist, for example, or even that any given person in Alabama is more racist than any given person in Colorado. That’s obviously not true. Instead, these maps reflect what is shared and common among people in a region. That can include laws, traditions, norms, monuments, culture. This study sheds light on structural contributions to intergroup bias.

"A lot of psychology is focused on changing hearts and minds. Hearts and minds are important, but that’s not the whole story,” Calanchini said. “This regional approach really brings the structural components of bias into relief. When you look at one of these maps, you can ask yourself what structures are in these more biased or less biased regions, and what can we do to change them?”

In addition to Calanchini, an assistant professor of psychology at UCR, authors of the paper, titled “Regional Intergroup Bias,” included Eric Hehman of McGill University, Quebec; Tobias Ebert of University of Mannheim; and UCR graduate students Emily Esposito, Deja Simon, and Liz Wilson.