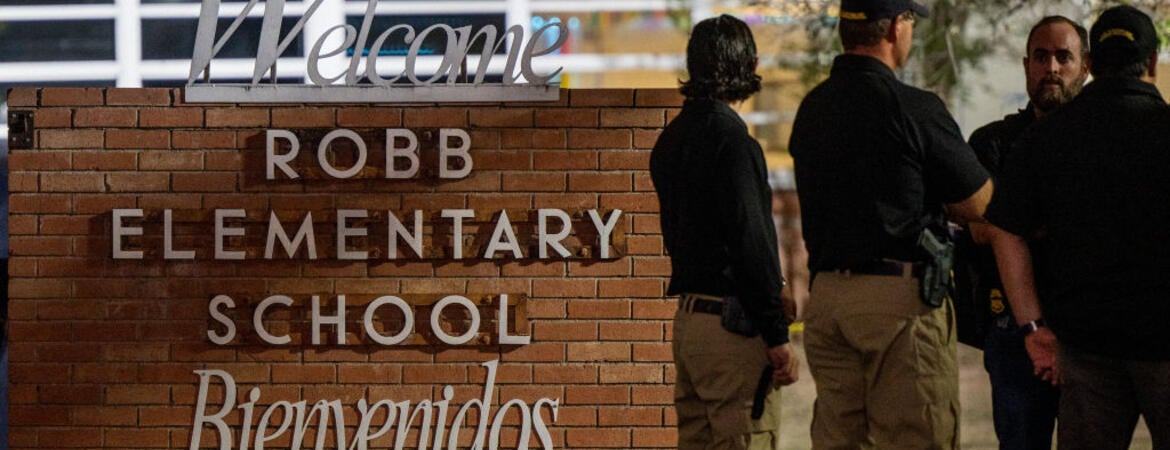

The routine has been too familiar for too many years. A school shooting or mass shooting event occurs and stirs the American consciousness for a moment. But a week or two passes and talk of gun-control legislation fades. The issue goes into hibernation until the next mass shooting event. In 2018, an opinion article by UCR political science Professor Ben Bishin was published in The Washington Post. It was Bishin's attempt to explain why the cycle keeps repeating itself, and who's to blame. This is a version of that column, updated this week by Bishin following the shooting at Robb Elementary in Uvalde, Texas that left 21 dead.

Q: What do we know about support for gun control nationally?

Nationally, and in most states, majorities favor a wide range of additional restrictions. In every state, majorities favor at least some additional restrictions and regulations on ownership and use. Reference the findings of this Gallup Poll: https://news.gallup.com/poll/1645/guns.aspx

Q: The National Rifle Association and the gun control lobby are often cited as the reason gun control legislation doesn’t advance nationally. Is that accurate, or is it more complicated?

Behind these lie something else, the power of what I call subconstituencies: shared groupings built around people’s strong psychological attachments, or social identifications.

By subconstituencies I don’t necessarily mean formally organized groups with dues-paying members. Rather, they’re groups that people feel a part of, based on a shared psychological attachment called a social identity, caused by some experience.

Consider, for instance, the fact that the NRA claims to have 5 million members. But between 7 and 9 percent of Americans identify as NRA members — which would be around 14 million. Beyond that number are others who share a similar “pro-Second Amendment” attachment or identity without identifying with the NRA. However, the views of those who identify as NRA members tend to be very different from others — even from others who own guns. This is how the NRA politically "weaponized" its membership.

These associations are very powerful. Group members act together to protect and promote the values of the group, and to oppose those of the out-group. These identities can be cultivated in a variety of ways, as the NRA has done by helping to bring people together, often through social interaction such as gun education, or with newsletters and more.

Once this “Second Amendment” identity becomes emotionally activated — as it does when gun regulation is discussed — people who share the identity work to defend the group and its related positions. The NRA’s effectiveness comes not just from mobilizing its members but from mobilizing the entire subconstituency — all those who share this identity.

Q: If it’s not the NRA, is the contentious nature of partisanship to blame for blocking gun control?

While opposing gun regulation may have become a signature partisan issue for the GOP, and partisanship itself is a strong social identification, not all share that faith. Many Republicans support some increased regulations, such as laws that would make it illegal to sell weapons to felons, the mentally ill and suspected terrorists. But those positions are not backed by a constituency as passionate as that affiliated with the NRA.

Consistent with others’ research, my book on subconstituency politics theory shows that politicians appeal and respond to identity-based groups because they are especially intense about an issue, especially when the group’s opponents are less intense or even politically apathetic on the subject. Politicians know that members of an identity-based group are much more likely to pay attention to the issue, to vote on the basis of the issue, and to be active in politics because of the issue. We see similarly powerful subconstituencies on issues such as LGBT rights, environmental politics and U.S. policy toward Cuba and recognition of the Armenian genocide. Opposing gun regulation is a voting issue for this group — while no comparable group votes just on regulating guns.

Q: How can proponents of gun control legislation offset the fervor of guns-rights proponents?

The answer seems to lie in finding a social identification that people hold strongly and tying it to the issue. A powerful social group identification can strengthens one’s attachment to partisan identity, which may explain the increase in partisan sorting.

Gun ownership used to be bipartisan. Not any more. One clue may lie in looking at where Americans already accept some restrictions on gun ownership and use: in airports, because of the fear of terrorism. Those restrictions have been framed not as about impinging on gun owners’ rights, but as offering safety from foreign terrorists, which has a subtext of racial threat. That may have been accepted because it reinforces rather than undercuts the Second Amendment subconstituency’s concerns; a great deal of gun rights advocacy, evidence shows, is driven by white racial anxiety.

So where would gun regulation advocates find a strong group identification to link to this issue? In one way, this is already happening. Research shows that people who live near mass shootings, which is a profoundly life-changing experience, more strongly support regulating guns.