Megan Asaka always knew her Japanese family had a place in Seattle history.

Though her family’s culture, language, and faces were omitted from school textbooks and tourism brochures, she was certain her community had a place in the city’s creation and development. Over the years, she found supporting family history, including the fact that her grandparents were incarcerated during World War II in California “enemy alien” camps, also known as internment camps. Her great-grandfather was detained in Montana after Pearl Harbor.

Through research during college, Asaka confirmed that all the cultural and historical contributions made by Japanese and other immigrant and Indigenous residents were not accidental omissions.

She set to change that.

In October, Asaka, assistant professor of history at UC Riverside, published her first book, “Seattle from the Margins: Exclusion, Erasure, and the Making of a Pacific Coast City,” by University of Washington Press. The book was primarily motivated by her own family story of migration, labor, and life in the northwestern city.

“Since I was young, I was already asking questions such as: Where do we fit in the larger story of Seattle? Of the U.S.?,” said Asaka, who spent the last 12 years interviewing Japanese American families, researching archives, and writing . “When I learned how early segregation had started in Seattle, I was surprised. Segregation started right when Seattle was created. This was not just a north-south division. City laws were being passed and in fact, it was Seattle’s native peoples, the Duwamish, who were pushed into segregation first. As immigrants came, they were pushed into the same kind of neighborhoods and districts.”

Asaka said these deliberate acts by white settlers created segregation and lifestyle restrictions — with ramifications for generations to come. Indigenous peoples and Asian immigrants could not choose where they wanted to live or work. They were essentially forced to become mobile workers, creating a circuit, following fishing, lumber, and agricultural jobs. It was a tactic to prevent people from setting roots, Asaka said.

Asaka said Seattle’s redlining only tells part of the story. White settlers removed Duwamish people by segregating them into the southern fringes of the city to take their lands.

Migrant workers including Filipinos, Japanese, Chinese, white and European laborers also settled in that southern periphery. Most of them were single men, a valuable source of labor for Seattle.

Among the stories Asaka highlights is that of Frank Kubo, a 16-year-old who took a transpacific steamship to Seattle in 1927. The three-week trip was a return to his birthplace; years prior his parents had been among the first Japanese migrants to arrive in Auburn, a rural town on the outskirts of Seattle. They were tenant farmers but lost the farm after going bankrupt and were forced to return home to Japan with their three U.S.-born children, including Kubo.

Asaka wrote that Kubo’s intention was to enroll in school and find a steady job to help his family. Instead, he fished salmon in Alaska. During the off season, he worked for a Japanese import company peddling food and supplies to Japanese labor camps; other months he worked at hotels and lodging houses.

The circuit of labor prevented him from pursuing an education. Many young men fell into similar cycles. “Seattle in the Margins” traces how the city was structured — spatially, socially, economically, and politically — around this demand for mobile labor. The book also offers readers a comprehensive look at how the lives of so many migrant workers intersected with one another.

“There is something about the West Coast that people think we didn’t have discrimination like in southern states. But it’s a fact, we did. It just manifested in different ways,” Asaka said, emphasizing the importance of studying segregation earlier than the 1920s.

Seattle was incorporated in 1869, with nearly 1,000 total residents at that time. Of those residents, about 33 were Chinese. By 1876 King County had about 200 Chinese residents. Japanese immigrants started arriving in the 1890s.

In the early 1880s, hop farms benefited from the low-wage labor Chinese and Indigenous workers provided. Japanese workers were essential to railroad companies, as well as to the lumber industry.

The unequal treatment of immigrant groups was obvious, Asaka argues. Scandinavians, for example, were seen as “the best class of foreigners,” and in turn were given better housing options, higher paying jobs, and allowed to join labor unions. This was not true for Japanese workers.

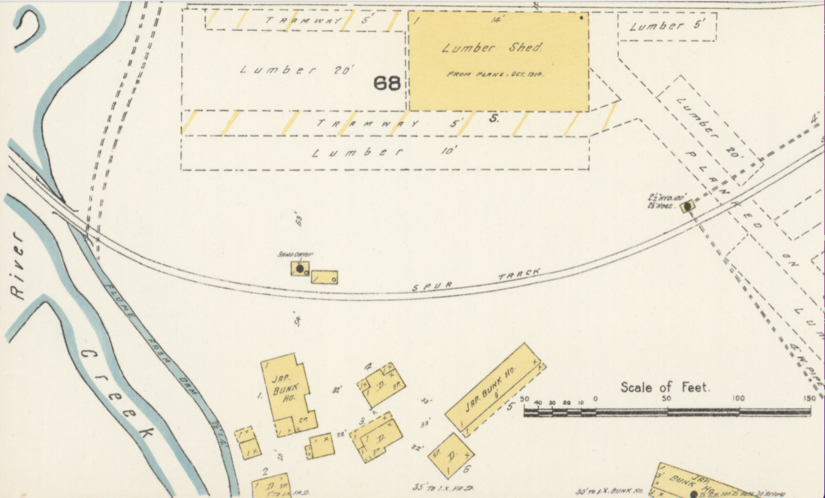

“Employers further entrenched this racial hierarchy by segregating the Japanese from other workers. Lumber companies, relegated Japanese laborers to isolated encampments, often deliberately situated near sites of industrial waste and nuisance — creeks that overflowed with refuse, lumberyards filled with sawdust. Japanese laborers who worked for Crown Lumber in Mukilteo lived in a muddy ravine called ‘Jap Gulch’ by local whites,” Asaka wrote in the book.

Additionally, federal laws excluded Japanese from becoming naturalized U.S. citizens. The many layers of discrimination and unfairness are difficult to ignore, Asaka said.

Asaka’s grandfather and great-grandfather experienced this discrimination, she said. Researching for the book also meant learning more of her own family stories. It was a process that was both humbling and fulfilling, she said.

“To learn that my family is part of this history, wow! I felt really empowered to finally see my family in the kind of social worlds that had been missing in Seattle,” she said.

Throughout the book, Asaka also highlights the strength of the human spirit, the ability to adapt and thrive in the worst of circumstances. Learning the history, listening to stories from these Asian migrant worker’s families, was grounding, she said. Most of her research began in college, through an internship with Densho, a Seattle-based organization dedicated to preserve WWII stories of incarcerated Japanese Americans.

Telling their stories, unearthing facts, is a way to reconcile this piece of omitted Seattle history, she said. Asaka’s research also showed the artistic side of these neighborhoods. Some wrote haiku poems about their work and their multiracial communities.

“The city viewed these workers as disposable, yet they refused to be disposable,” Asaka said. “They created their own families, they created communities — amazing multiracial communities that formed organically. There were tensions, of course, but they learned to live with each other and coexist.”