The narrative surrounding the virtues of yoga instruction inside prisons is incomplete, according to a UC Riverside professor who taught yoga in prisons for several years and has written a book about the experience.

“There is a false narrative, which is ‘if you improve yourself, you won’t get incarcerated,’” said Farah Godrej, an associate professor of political science. “Inside prisons, this idea of self-improvement is used in a way that’s insidious. It becomes an apparatus for telling incarcerated persons that incarceration is their own fault.”

In her just-published book, “Freedom Inside? Yoga and Meditation in the Carceral State,” the author argues that the power of yoga and meditation can be taught more thoughtfully by including an awareness of the structural and systemic injustices that lead so many into the prison system.

Godrej’s first exposure to yoga was in her native India, in her 20s. It was during this time she read the Bhagavad-Gita, one of yoga’s canonical texts, along with the Yoga-Sutras, and other similar texts. These texts teach inward spiritual pursuit, to accept without reaction, and to detach from worldly circumstances. Aided also by her study of Buddhist traditions, she at first adopted the view that the key to happiness isn’t changing external circumstances, but rather one’s internal state.

But that message also gave her pause: “What about collective suffering? Are we supposed to accept inequity and injustice as part of the fluctuation of life, or worse, as created by our own minds?”

Godrej’s book makes a compelling case to consider the “prison industrial complex.” That’s the term many use to describe the system of interests that profit financially from prisons, including unions and lobby groups, private prisons, and businesses that supply goods and services (including bail) to prisons.

Godrej cites evidence demonstrating that 2.3 million people are in U.S. prisons, 10 times the rate of comparable democracies. One in 23 American adults are in some way part of the system, most of them from underrepresented demographics. And one in two American adults have had an immediate family member incarcerated. She also cites evidence regarding prosecutorial discretion and sentencing laws, along with discrimination and structural rules that tend to trap people from certain communities in cycles of repeated incarceration.

Simultaneous to her studies of mass incarceration, Godrej became aware that many organizations were offering yoga and meditation in prisons. She found that the lessons being offered paralleled those from yogic and Buddhist traditions with which she was familiar: downplay external causes, focus on internal ones. Prison yoga proponents preached being nonreactive toward and accepting of injustice.

Godrej had by then become more predisposed to a message closer to that of Mahatma Gandhi, who advocated nonviolent but disruptive action.

She explored volunteering to teach yoga in prison, while simultaneously seeking approval to conduct research. Prisons are notoriously closed to outside scrutiny and gaining scholarly access for research required two years of appeals and assurances to prison officials.

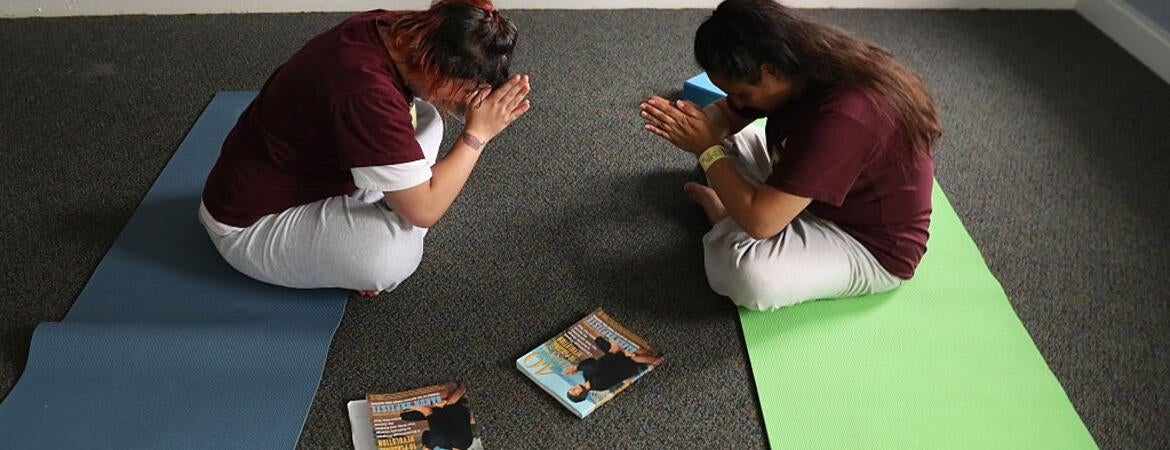

Between August 2016 and March 2020, Godrej’s weekly routine included driving to different prisons across Southern California, often traveling long distances, where she would lead yoga and meditation sessions. During that time, she writes, she became “immersed in the landscape and logistics of prison life” while getting to know many students.

Godrej’s approach to instruction was informed by her extensive immersion in the prison landscape, including in-depth interviews with other volunteers, and attendance at training offered by different organizations operating inside prisons. She gravitated toward approaches that linked yoga and meditation to their potential to address structural and systemic inequalities, including race, gender, and socioeconomic inequity.

Godrej found that many who practiced yoga while incarcerated reflect the words of Alex, a formerly incarcerated practitioner who adhered to the notions of personal responsibility and accepting consequences.

“One thing Buddhism and meditation did for me… no matter what you do, it took a decision, and everything has a consequence. I manned up to it, and accepted responsibility for my actions,” Alex told Godrej.

Another practitioner, Lucas, said: “It might have been through meditation that I was able to accept (my sentence) enough that it didn’t bother me so much.”

Godrej emerged from her four years teaching yoga in prisons with a lesson far more nuanced. She said there are indeed many benefits to a foundational lesson in spirituality, to accepting responsibility as a step toward self-improvement. But she believes acceptance, while a valuable lesson in prison yoga, shouldn’t be the final lesson.

“All too often… I watched as teachers and students inside prisons treated acceptance as the end goal of these practices, neglecting to mention that acceptance need not mean resignation, reconciliation, or passivity toward injustice,” she wrote.

Her book includes interviews with 36 other yoga and meditation prison volunteers. Godrej wrote that most volunteers believe in the need to reform prison into a vessel for personal change, to make prison time “productive, introspective and redemptive.”

Godrej prefers what she calls “the dissenting narrative."

"I found that practices of self-control and self-discipline could help incarcerated practitioners to develop an internal strength and sense of freedom that defied the institution’s capacity to define their lived experience,” she said.

Or in the words of Michael, another formerly incarcerated person quoted in the book, meditation “teaches us to see our conditioning; it taught me how to think and how to inquire, not just internally but also externally.” He said it provides “a moral compass” with which to navigate the world.

Godrej’s book concludes by urging yoga instructors to consider more thoughtfully the messages they disseminate inside prisons. It also offers beginner-level lessons on various traditions and lessons of yoga and meditation and explores prison culture and its volunteer dynamic.

“Freedom Inside” was published by Oxford University Press. It is available via online retailers, and at Vroman’s Bookstore in Pasadena and Skylight Books in Los Angeles.

On Jan. 25, 2023, the Center for Ideas in Society at UCR will host a book presentation by Godrej. The Center also provided research funding for the book.

Lead photo by John Moore, Getty Images