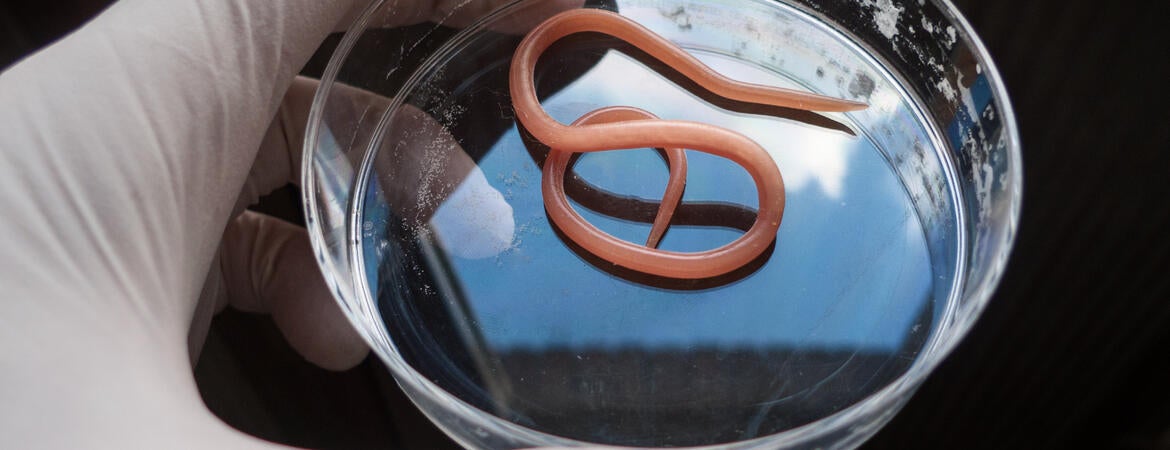

Has the news about an Australian woman with a living, wriggling roundworm in her brain got you spooked?

After experiencing abdominal pain and night sweats that developed into forgetfulness and depression, the 64-year-old woman was sent to a hospital. An MRI scan did reveal something unusual in her brain, but the roundworm was not discovered until the surgeon peered into her skull.

Normally, this type of worm only infects snakes. This unprecedented discovery in a human surprised physicians and scientists alike, so it’s natural for the rest of us to have questions, too. Could this type of roundworm pose a threat closer to home? Is this what the next pandemic looks like?

Here to address everyone’s new worries about worms: UC Riverside experts on infectious roundworms, also known as nematodes. Two nematology professors and a professor of biomedical sciences weigh in on what happened in the Australian case, which worms pose a threat in California, and the best ways to avoid infections.

Simon “Niels” Groen is assistant professor of evolutionary systems biology in UCR’s Department of Nematology. He typically studies the effects of plant chemicals on interactions between hosts and parasites.

Q: Now that it has been documented infecting a person, how concerned should the rest of us be about this worm?

A: Even though they’re mostly found in pythons, from time to time they can end up in other animals. They’ve been recorded as infecting a koala, as well as rodents and now a human. This does suggest they can infect a wider range of species than the one they’re normally associated with.

It is not known whether these parasites can generally infect humans more broadly, or even other species of pythons. More research is needed to learn that, and these knowledge gaps create the opportunity for us to be surprised by new infections. However, parasites and pathogens are usually relatively host specific.

This particular nematode’s behavior is surprising. It was able to cross the blood-brain barrier and enter the nervous system. Few nematodes can do that in any host, human or animal.

Though there may be additional infections in the future, I don’t think there is a reason to be very worried that this worm will start infecting a lot of people. The worm they found in this woman got through several barriers. They suspect there were nematode eggs on leafy greens that she foraged. Also, it has been reported that the woman was immunocompromised.

Normally, if we eat nematode eggs we’d release them in our stool, and nothing happens. For most species of nematodes, that’s how we get rid of them. In many other cases, the human immune system takes them out.

Nematodes are among the most abundant animals on Earth, only a small fraction of them are parasites of humans, animals, or plants. However, the infectious ones can do a lot of damage.

Q: How did this woman get infected in the first place and how can readers avoid doing what she did?

A: It is suspected, again, that there were nematode eggs on greens harvested from an area near a lake, where the python hosts are common. If the woman in Australia had thoroughly washed the greens, she may not have become infected, though we’re not completely sure.

Generally, washing your greens will get rid of the eggs. Wash your hands, and your greens, and definitely cook your meat and your fish. Eating sushi carries a risk, in this sense. Infectious nematodes can be found in tuna and salmon. We need a good food monitoring system to check for the occurrence of these worms and their eggs.

The FDA and the CDC advise that greens should be washed in running water. Although the best length of time the greens must be washed for has not been determined, I would perhaps follow the CDC’s recommendation for washing hands, which is to wash for 20 seconds at least.

Don’t panic. Just make sure to be clean. This was a unique occurrence. Pinworm, hookworm, and Ascaris are the ones we should generally continue to be vigilant against.

Q: Where do hookworm and pinworm show up?

A: Hookworm and a couple of other nematode parasites infect up to a quarter of the population in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Central and South America. There are some species that occur in Southern California, but typically they aren’t as big a problem in our part of the world.

Pinworm, however, is common in children. While an infected person sleeps, female pinworms lay thousands of eggs in the folds of skin around the anus. People can experience anal itching and restless sleep. Then the worms can enter the gut after the eggs have hatched and infect the intestines.

The eggs can easily spread from child to child. Skin to skin or even skin to clothes contact can spread it. There are common compounds, benzamidazoles, that can treat this, although increasing roundworm resistance to these compounds is a phenomenon of concern.

Adler Dillman is professor of parasitology and chair of UCR’s Department of Nematology. His laboratory studies host immune responses to parasites, and how parasites evade or suppress immunity.

Q: Given that occurrences of nematode infections are lower here than in some other places, is there a danger that people won’t take precautions, or recognize infections when they occur?

A: It’s true that most doctors aren’t used to diagnosing this kind of thing. It’s interesting. I’ve been teaching parasitology since 2015, and I typically have 200 students. I always ask them which parasitic nematodes we have in the U.S., and they’re all under the impression that we don’t have them here.

Take trichonosis, which is usually caused by eating undercooked meat, like pork. In some places like Alaska where people eat more hunted game meat like wolf or bear, there is a danger of contracting trichinosis.

Q: What other kinds of infectious worms pose a threat in California?

A: Officials in San Diego, Orange, Los Angeles, and Riverside counties are concerned about a parasite of dogs. They contacted me last year to help them figure out where it’s coming from. The parasite, Heterobilharzia americana, can cause dogs to get lethargic, lose their appetite, and even kill them in a matter of months if it isn’t treated.

My students and I have pinpointed a portion of the Colorado River, where it crosses into the state from Arizona, in a town called Blythe. It’s pretty wild because it was never known to be this far west.

Dogs are getting it because it’s hot, so they’re jumping into the water. The worm can penetrate the skin of the dog and enter the bloodstream. It then lays eggs that lodge in the liver, which can cause inflammation and liver failure.

There is some evidence to suggest it could transfer to humans and potentially cause liver damage, but this is not something that has been studied very much. Ethics and cost have limited study of these organisms in primates.

Prevailing wisdom is that if infected, humans might get itchy, but not have as severe an infection. Once in humans, our immune system usually takes them out. They generally don’t get into our bloodstream. At least, that’s what we believe for this particular parasite.

Emma Wilson is professor of biomedical sciences in UCR’s School of Medicine, and associate dean of the school’s graduate division. Her lab is primarily focused on the immune response in the brain following Toxoplasma gondii infection.

Q: Any advice for parents wondering whether their child has an infection?

A: Enterobius, more commonly known as pinworm, is the most common worm infection in the U.S. You may not believe this, but kids don’t always wash their hands. They put their fingers in their mouths and transmit the eggs after scratching their backsides. To work out whether a child is infected you can use sticky tape overnight. When the worms crawl out of the anus, they get stuck, and you can observe them on the tape. I advise getting medication quickly to clear these parasites.

Q: Thoughts on other common worm infections?

A: Tapeworms are eaten in undercooked meat, especially pork. These are really large worms that lie in the gut, but don’t cause much pathology. However, if the eggs that are shed in feces are ingested then they can get lost in the human host — just like the python parasite. Those eggs hatch and the larvae can migrate to the brain. If that occurs, it causes significant symptoms. This is called neurocystercicosis. Adults that suddenly cultivate epilepsy may have this infection.

Pets can harbor worms, and it’s really important for their health and human health to get dewormed regularly by the vet. Larval worms for these parasites can also get lost in humans and cause disease, so please deworm!

(Cover image of nematode: piola666/iStock/Getty)