On the second floor of the California Museum of Photography, a catwalk leads to the exhibition, “Jon Henry, Stranger Fruit.” At the end you see a portrait lit on either side by chrome light tubes on a purple wall. Below the shadowy catwalk, light shines up from the first-floor exhibition “David C. Driskell and Friends: Creativity, Collaboration, and Friendship.” On the catwalk, stop and read the poetry on plaques affixed to the handrails. The poetry is by the mothers in the “Stranger Fruit” photographs. It will add resonance to what you are about to see.

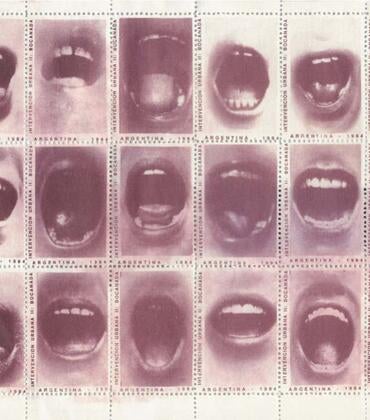

“Stranger Fruit” takes its name from Billie Holiday’s 1939 song, “Strange Fruit,” whose writer was inspired by a photograph of a lynching.

“Instead of Black bodies hanging from the poplar tree, these fruits of our families, our communities, are being killed in the street,” said Henry, a New York-based visual artist.

The project is rooted in the killing of Sean Bell by undercover police officers in 2006 as he left his bachelor party. Years later, Henry found himself in a car going to a bachelor party. Bell’s death haunted him. At any minute, he could be another dead son leaving behind a grieving mother.

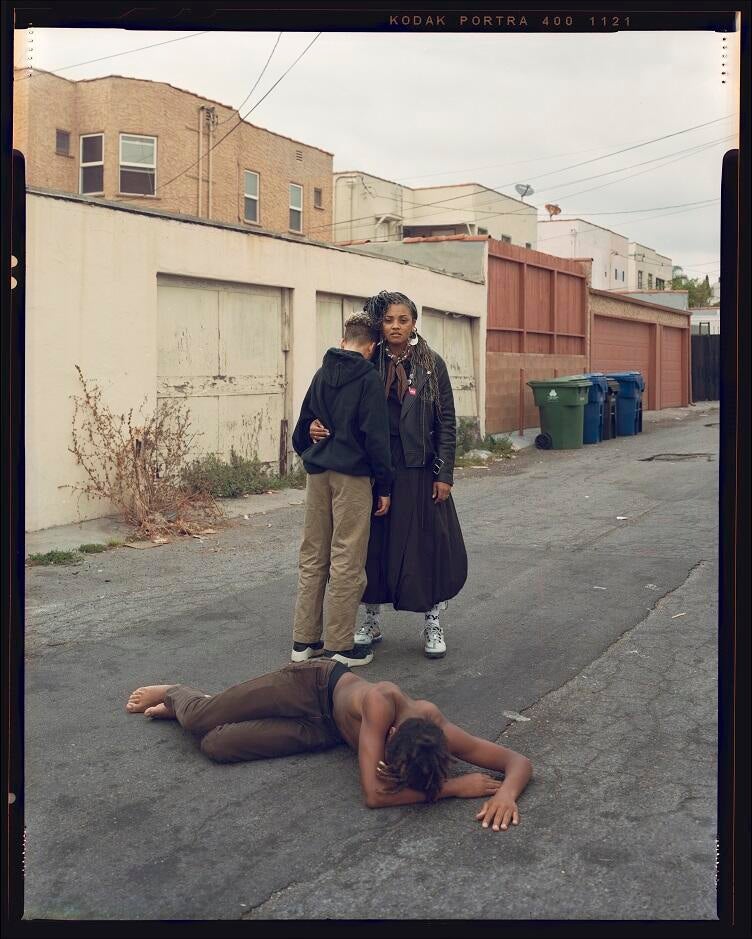

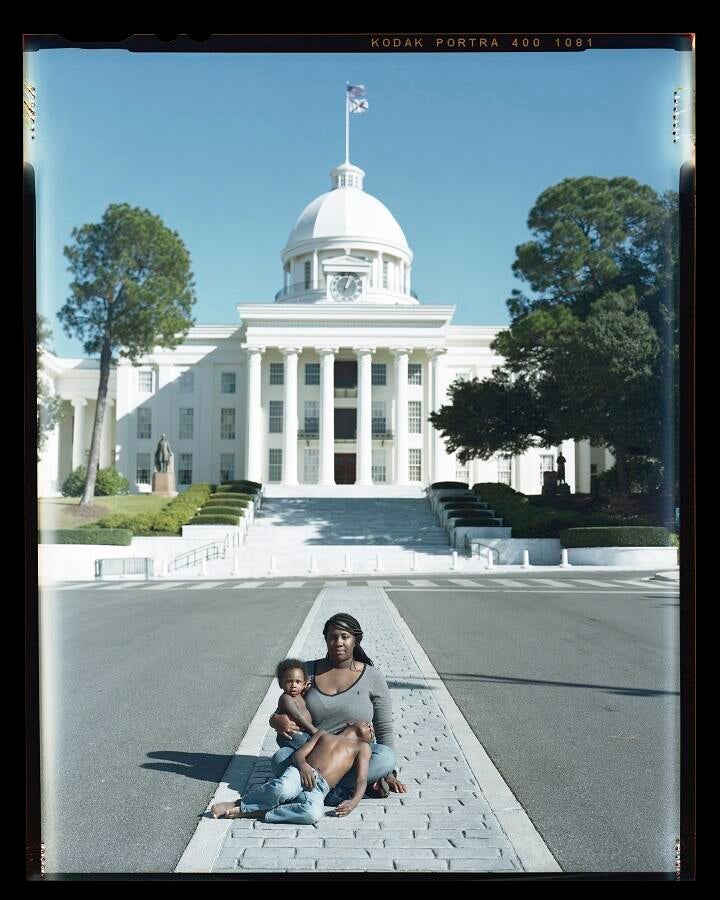

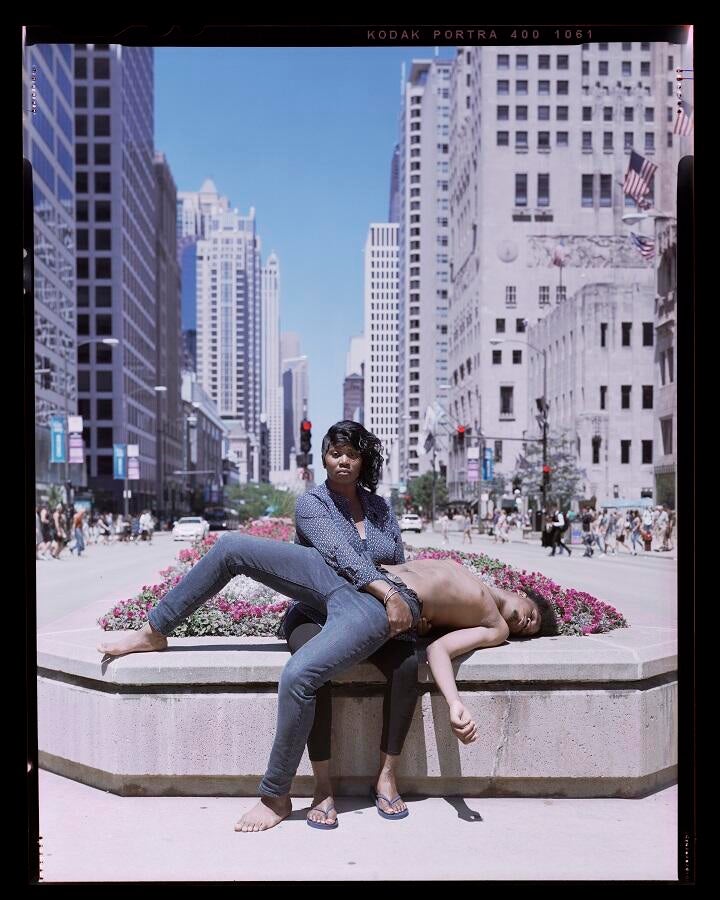

Inspired by Michelangelo’s sculpture “La Pietà,” other Renaissance artists, Renée Cox’s photograph “Yo Mama’s Pieta,” and David Driskell’s painting “Behold Thy Son,” Henry travelled America to photograph Black mothers and their sons posed as Mary holding the crucified Christ’s mortal body.

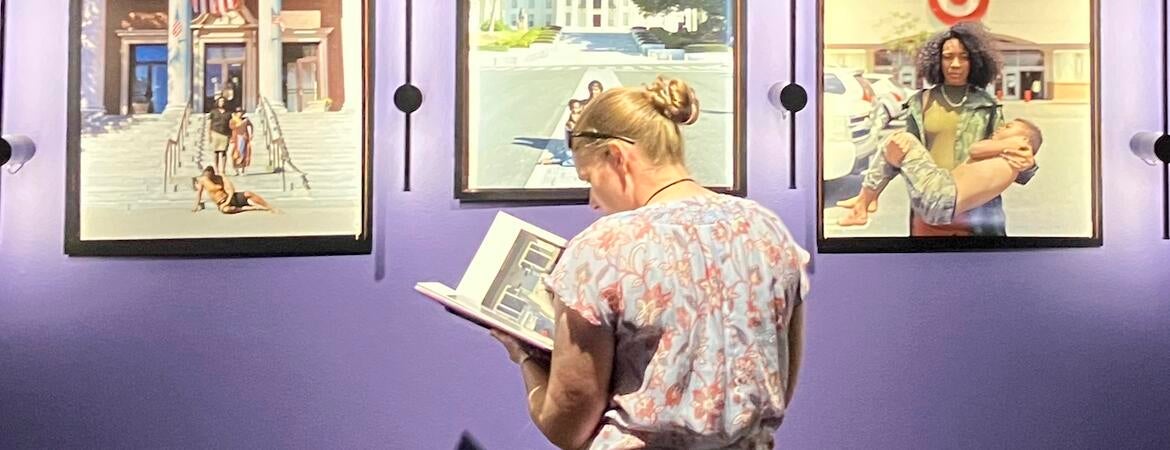

Lights illuminate only the 30-by-24-inch photographs, so viewers move in the shadows. The fixtures remind one of candles framing a religious icon like an altar panel. Opposite the entrance, the center photo is mounted highest with images hung descending to the left and right. On the other walls images hang in variations of this symmetry. It feels like entering a chapel.

The printed edges of the 4-by-5-inch large-format negatives serve as the borders.

“The film border is just to reinforce the idea that there is no manipulation going on,” Henry said. “This is the reality for these families at this moment.”

The framing has an unintended effect. Instead of the emotional expressiveness of Renaissance art, you are confronted with an art that flourished in the Middle Ages: Stained glass windows. Images depicted in stained glass tell stories of sacrifice and evoke contemplation. They are flat, yet colors vibrate with sunlight in three dimensions, as Henry’s images do.

Faces in stained glass, for the most part, show little emotion, unlike the later depictions of Pietà. All the mothers in Henry’s photographs, one viewer commented, “have the look of plague survivors because they have witnessed so much death.” This emotional dampening parallels the staged poses in public areas, the way the sons hold themselves, and the photographs’ flatness despite the rural or urban space around them.

Of the neutral gaze, Henry said he wanted the “viewer to land on each image and contemplate what could be going through the mothers’ minds. It is a combination of grief, fear, exhaustion, and so much more.”

From their “neutral” gaze, though, they sing with light and color, creating tension between the image's beauty and the horror of mothers grieving for sons murdered by the state – Roman or American.

Inherent in Pietà, is the promise of resurrection and washing away sin. That is missing here. Walt Whitman wrote about a dead Union soldier:

I think this face is the face of the Christ himself,

Dead and divine and brother of all, and here again he lies.

“Again.” Maybe redemption comes only after the war ends. Salvation and forgiveness are impossible until the killings stop.

The show opened September 23 and runs until Feb. 11, 2024. For more information, visit the UCR Arts web site.

The lead photograph, taken in the California Museum of Photography "Stranger Fruit" gallery, is by J.D. Mathes