A new research study found that aunts play a crucial role in supporting the well-being of their LGBTQ youth relatives, including preventing them from experiencing homelessness.

These findings were published in Socius, an open access journal of the American Sociological Association. The research paper, coauthored by Brandon Andrew Robinson, associate professor and chair of the University of California, Riverside’s Gender and Sexuality Studies Department, is based on a longitudinal study of 83 LGBTQ youth from the Inland Empire and South Texas, two geographic areas identified as understudied places in LGBTQ research.

The paper, “Aunties, Aunts, and Tías: The Forgotten Othermother Supporting and Housing LGBTQ Youth,” describes the first research focusing on LGBTQ youth and aunthood, an under-researched category in social scientific work on families. Results were captured by qualitative interviews with the youth study participants in the summer of 2022.

Robinson and the research team found that aunts, aunties, and tías (Spanish for aunts), offered housing stability and harbored emotional safety for their LGBTQ “nibling,” the gender-neutral term for the child of a sibling. This work is part of the Family, Housing, and Me Project, or FHAM Project, co-led by Robinson and Amy L. Stone, sociology and anthropology professor at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas. Stone and UCR postdoctoral student Javania Michelle Webb are the paper’s coauthors.

The paper also highlights the important roles aunts play specifically in families of color. Moreover, by focusing on aunts, this research challenges traditional family research, which tends to look at social dynamics and interactions between parents and children, and often focuses on the rejection by parents toward their LGBTQ child, Robinson said.

The paper also discusses othermothers, or women who assist biological and adoptive mothers in mothering their children. Othermothers can be sisters, aunts, grandmothers, and “fictive kin” — a term that identifies those not related by blood but having a close relationship to someone who has children. Fictive kin tend to be crucial parts of extended kin networks within Black, Indigenous, and Latinx families, Robinson said.

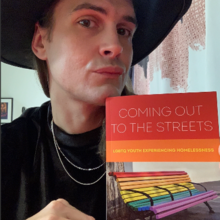

“This study joins other scholars in not only decentering the nuclear family but also in interrogating what is missed in the lives of LGBTQ youth if scholars only focus on parent-child dynamics,” said Robinson, author of the 2020 book “Coming Out to the Streets: LGBTQ Youth Experiencing Homelessness.”

Another reason for focusing on aunts is because these relatives often offer LGBTQ youth acceptance and space to be seen for who they wholesomely are.

“Parents are often uniquely invested in their child’s gender and sexuality, as parents often see their child’s gender and sexuality as a reflection of their own parenting,” Robinson said. “For instance, fathers often try to raise masculine, heterosexual sons, as fathers tend to see their son’s gender and sexuality as a reflection of the father’s own masculinity.”

This type of conscientious or unconscientious behavior is interpreted by LGBTQ youth as “gender policing” and in turn often drives parents and children apart. Some parents — of all social, ethnic, cultural, and economic backgrounds — may not support their child being LGBTQ, and aunts and othermothers step in to help, including, at times, providing housing support.

Aunts, aunties and tías, in addition to taking these youth into their home, also demonstrate their support by following their youth relative on social media, by educating other family members about LGBTQ topics and gender pronouns, and by welcoming them into their home.

“Aunts acted as a buffer between the youth and other family members, especially parents, and provided consistent loving and affirming support,” Robinson said.