In 1838 Louis Daguerre, inventor of the daguerreotype, captured an image that looked down on a mostly deserted Parisian street. On a corner of Boulevard du Temple, the small form of a bootblack and his customer can be spotted, representing the earliest depiction of humans in a photograph. During this early period of photography, exposures were so long that moving things, such as people, carriages, dogs — any of the hustle and bustle of a city street — disappeared from the photographic plate. The camera could not catch anything in motion. The bootblack and his patron, however, had simply stayed in one place long enough.

As technology advanced, photographers would begin to take photographs of objects in motion, but there were still limitations. A turning point came when industrialist and former California governor Leland Stanford made an alleged bet. It’s rumored he wagered a friend that, while galloping, all four legs of a horse were off the ground simultaneously. To prove his point, Stanford contracted famed English photographer Eadweard Muybridge, known for his images of Yosemite, in 1873 to conduct a series of motion studies.

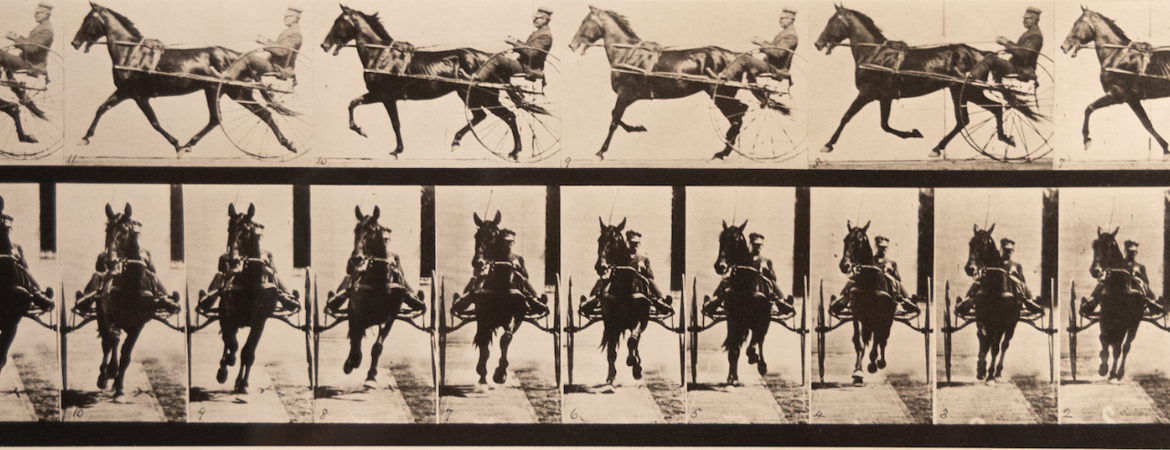

It wouldn’t be until 1878 that Muybridge captured a horse’s full stride at a run in a series of photographs. Muybridge’s “The Horse in Motion” was created using a battery of cameras whose shutters were triggered when the wheel of the driver’s cart successively tripped a wire connected to each camera as horse and driver raced around a track. The resulting images sparked controversy as people long believed a horse always had one hoof on the ground. Muybridge’s photographs revealed centuries of art depicting horses were incorrect. In 1887, he released the eleven-volume collection “Animal Locomotion” detailing the results of his years studying living things in motion.

Viewers today can watch Muybridge’s famed horse gallop in a zoetrope as part of the ongoing exhibition “Movement Exercises (After Muybridge)” at the California Museum of Photography, or CMP, a part of UCR Arts in downtown Riverside. Beginning with several of Muybridge’s studies, the exhibition guides viewers through a selection of chronographic images captured in the wake of and influenced by Muybridge’s revolutionary work.

“Beginning the exhibition with Muybridge is a fitting way to frame the show as, first of all, the museum has several dynamic works by him, and secondly, you can’t really tell a story about motion and photography without him,” said the show’s curator, Ashley McNelis, a CMP Curatorial Fellow and UCR art history doctoral candidate.

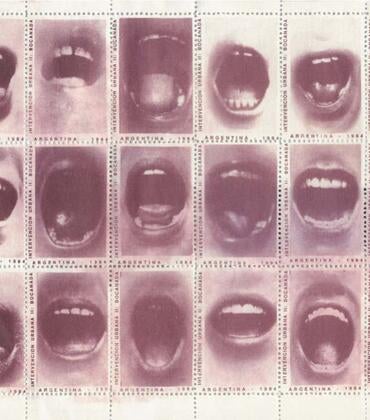

The exhibition includes images to be viewed with a TwinScope stereoscope, early film clips, dancers, laborers, skiers, party goers, and bustling street scenes depicting the changing urban landscape. Interested in photographic images of movement depicting labor, McNelis selected images from the CMP’s collection reflecting this subject in particular.

“It was both daunting and exciting to be tasked with creating an exhibition from the vast CMP holdings, but I was immediately drawn to many of the photographs in their collection that freeze motion,” McNelis said. “The exhibition tracks the status of the body in modernity through works that visually or conceptually parallel Muybridge’s motion studies.”

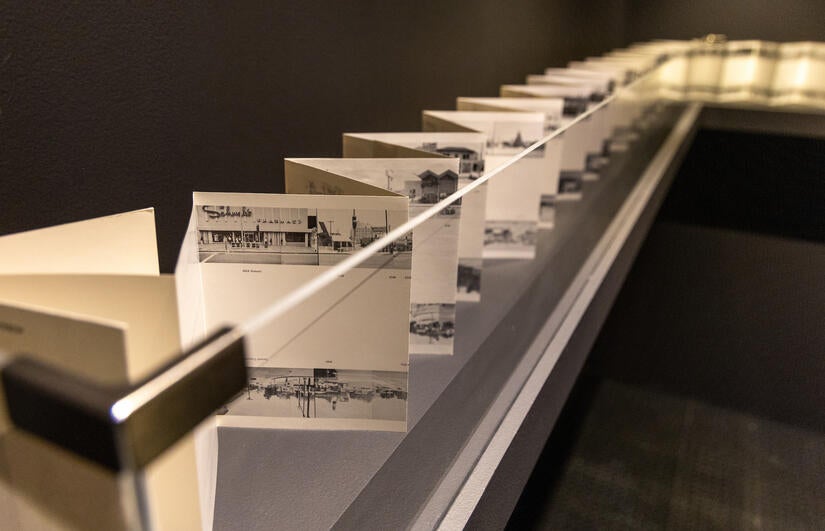

Also included is Edward Ruscha’s 25-foot-long accordion-format book “Every Building on the Sunset Strip,” created in 1966. Instead of using a row of cameras and trip wires to capture a moving horse, Ruscha mounted a motorized camera onto the back of a pickup truck and drove it down Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles. This time, the camera was in motion and the subjects fixed. Google’s Street View cars came 41 years after Ruscha. Viewers are left to wonder what will follow.

“Movement Exercises (After Muybridge)” is on view at the CMP through July 7. Exhibitions at UCR Arts are supported by the College of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences at UCR and by the City of Riverside.

Header Image: Close-up of “Animal Locomotion” by Eadweard Muybridge. (UCR/Stan Lim)