When we consider the staying power of U.S. democracy, it’s humbling to consider the Roman Empire’s longevity of 1,500 years. On Oct. 22, UC Riverside's Michele Salzman will co-host in the ancient Roman Senate House a conference named “The Senate: From Antiquity to Modern Times.” If you happen to be in Rome, the event is free to attend. The rest of us can attend at no cost by registering on Zoom.

The influence of the Roman Senate waned and surged, then waned again, during its 1,500 years, but it remains the most long-lived example of representative government. We asked Salzman about lessons that could be applied to modern American politics. Salzman, who has been on the UCR faculty since 1995, is a distinguished professor of history, and is author of the books "On Roman Time: The Codex-Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity," published in 1990; "The Making of a Christian Aristocracy, published in 2002; "The Letters of Symmachus: Book 1," published in 2011 and 2012, and "The Falls of Rome: Crises, Resilience and Resurgence in Late Antiquity," published by Cambridge University Press in 2021.

Q: We have the idea that modern U.S. politics is uncivil, even uniquely so in a historical context. How does the civility of the current U.S. politic theater measure against the Roman Senate in its heyday?

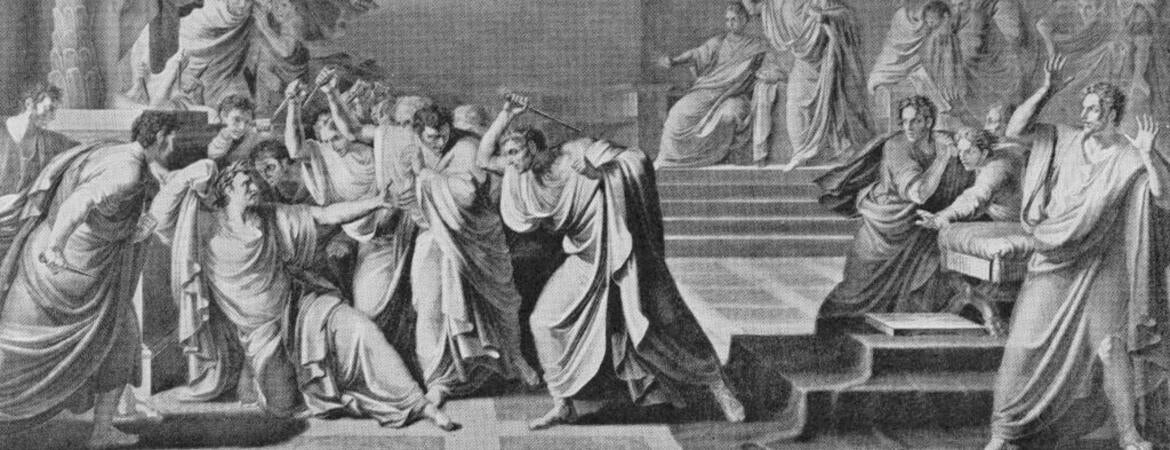

Salzman: Actually, debate in the Roman Senate could get quite fierce. In my paper I discuss a virtual riot that broke out in the Senate in the late fourth century CE. The senator, Symmachus, is embarrassed to note it, but it did happen. And of course, Caesar was killed by senators in a meeting of the Senate held in the Theater of Pompey. So violence did happen, but it was seen as shameful. After the civil war with Mark Antony and Cleopatra, the victorious new ruler, Augustus, the first emperor, tried to revive the prestige of the Senate. He set up an Altar and Statue of Victory to remind senators of his power, but also of the need for some measure of decorum. Each session began with prayers and offerings to this goddess, allegedly.

Q: Was there an equivalent at any point(s) to the far-right – what some now call “Christian nationalist” movement that carries much influence in the current U.S. Republican party? If so, did that movement persist, or do such ultra-conservative movements within a democracy typically have a defined half-life?

Salzman: It is interesting that in the late republic, the conservatives, Optimates, were unwilling to compromise with Caesar. They chose their own leaders, including Pompey the Great. And as civil war broke out, they ultimately lost to the populist party, led by Caesar, a great general and a great politician who was able to unite his reputation and honor with that of the freedom of the people of the Roman republic. I am not sure this is analogous, but it does give one cause for concern. Of course, Caesar’s populist successor, Mark Antony, ultimately fell and after another civil war, Augustus returned to a more measured position.

Q: Abortion may be the most divisive sociopolitical issue in our time. In terms of the intensity of polarization and debate, was there an equivalent in the times of the Roman Empire? If so, with what degree of success was that divide navigated?

Salzman: I work on the later Roman Empire. After the defeat of his rival, Maxentius, Constantine entered Rome and adopted Christianity as his personal religion. Over the course of the fourth century, Christianity was supported by later emperors, and by the late fourth century, animal sacrifice in public was forbidden. Yet, the majority of the senators in the senate in Rome remained pagan through to the end of the fourth century. When the Christian emperor Gratian removed the Altar of Victory from the Roman Senate, it became a rallying cry for religious toleration. No less than six senatorial embassies tried to have the altar and statue returned. The argument for religious toleration and pluralism – “There is more than one road to the truth” – was the rallying cry of the late Roman senator Symmachus. Christians opposed him, including the bishop of Milan, Ambrose, who put outside influence on the emperor Gratian to deny the request for a return to a policy of religious toleration. Ultimately, the Senate became Christian, but without a civil war. So, the divide was overcome in time, and tolerance for pagans and Christians for the fifty years prior to the efforts of Symmachus are noteworthy.

Q: When we look back on the history of the U.S. Senate, the giants include names like Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, Richard Russell, Lyndon Johnson, and Ted Kennedy. All were tacticians first, and also effective orators. Who were the giants of the Roman Senate, and who are their closest equivalents in the modern U.S. Senate era?

Salzman: The giants of the Roman Senate emerge especially in the late Republic – Cicero, of course, rallied the senate to vote to put to death Catiline, whose conspiracy threatened the very survival of the state. Interestingly, Caesar argued against putting Catiline to death. He failed in the face of Cicero’s eloquence. So, too, Cicero’s famous speeches against Mark Antony, the Philippics, drove Mark Antony from the city. Sadly, civil war ensued and Cicero was murdered, his tongue allegedly removed and used as a pin cushion by Mark Antony’s angry wife.

Q: Did the Romans typically mobilize quickly during crisis? Can you offer an example? Is that a cornerstone of effective government?

Salzman: At times they mobilized, but only after much internal debate, and often not quickly enough! When the general Stilicho requested money from the Senate to prevent the Gothic general Alaric from sieging and attacking the Senate, some senators refused on the grounds that this was cowardice. Ultimately, they did raise the funds. But it took more time than needed, and eventually, Alaric attacked and took the city in 410, the first time the city was sacked in 800 years. So, no, not soon enough.

Q: Please explain the focus of the Oct. 22 conference. How did it come together – in Rome? How does one reserve the Roman Senate House?

Salzman: I have long pursued research in Rome, and I have been associated with the American Academy in Rome for many years. My first book took me to Rome to work at the Vatican Library on Renaissance copies of a lost Carolingian copy of the lost fourth century CE copy of the Codex-Calendar from the year 354 CE. I conceived of the idea for the conference, looking at the Senate from Antiquity to modern times. I applied to the American Academy for funding, along with my colleague, Professor Ed Watts of UCSD. The Director of the American Academy, Aliza Wong, was very supportive and funding was made available through the American Academy and through the University of California Consortium for Late Antiquity. The American Academy has helped with the arrangements with the assistance of Francesca Boldrighini, who is an archaeologist working in the Parco archeologico del Colosseo. (She is excavating, and will be presenting a talk: "From the Curia Iulia to the Church of St. Hadrian and Back: a brief Historical Summary." Additional funding is from the Center for Hellenic Studies at the University of California at San Diego, the Vassiliadis Endowed Chair, and the UCSD Institute for Arts and Humanities.

Q: Can you provide for our readers a link to research/reading that would help frame the upcoming conference?

Salzman: The conference arose because of my research for my last book, "The Falls of Rome: Crises, Resilience and Resurgence in Late Antiquity" (Cambridge University Press, 2021). The importance of the Senate as a focal point for the resilience of the Roman senatorial aristocracy and for emperors and generals was an important theme of that book. The last chapter looks at the demise of the Roman Senate in the early seventh century. The longevity and vitality of this institution is impressive, from the earliest republican formation of it, allegedly in the 8th century BC, down through the seventh century CE. Of course, the Senate as a body changed. So the Senate in the Empire, as the book of Richard Talbert "The Senate of Imperial Rome" (1984) showed, is different from that of the Republic. But there is no modern treatment of the period, nor one that considers the idea of the Senate that has lived on to influence men and women in the Middle Ages, in the making of the Italian Republic, and in America, of course.

Feature image credit: The assassination of Julius Caesar (100 - 44 BC) at the Senate in Rome, 15th March 44 BC. (Photo by Archive Photos/Getty Images)