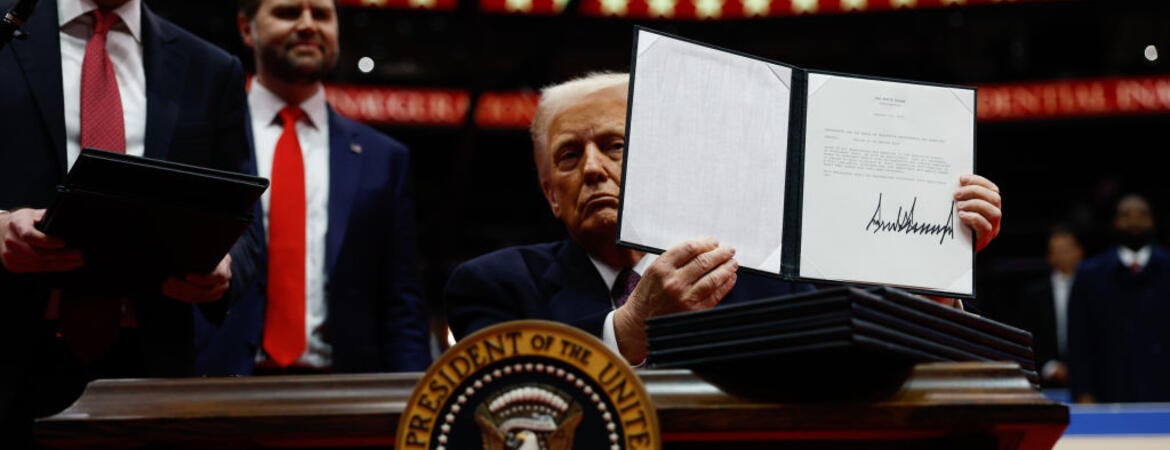

Immediately after his inauguration, Donald Trump signed dozens of executive orders. Some, such as his pardon of about 1,500 Jan. 6 defendants, took effect immediately. The path forward for many other orders is less certain. We asked Nicholas Napolio, a UC Riverside political scientist and expert on presidential powers, to weigh in on the breadth, and the limits, of a president's executive orders.

Q: What was the framers’ intent with regard to executive orders?

Napolio: The framers were quite vague about the powers of the president. The Constitution says only "The executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America" and lists some specific powers like pardons and appointing other governmental officials.

The framers disagreed quite a bit about how powerful the presidency should be. Some thought a more empowered president would be a good thing because it would allow the government to act quickly (or "energetically" in the language of the time), others were fearful that a strong president would devolve into a tyrant like many early Americans felt King George had. As a result, the framers had no single "intent," but rather each had a different intent which aggregated into a very vague Article II detailing what the presidency was and could do. Over time, presidents began acting unilaterally, and on many occasions Congress and the courts allowed those actions to stand.

Q: "Executive order" sounds definitive. But it is an "order" - can it be executed without challenge?

Napolio: On a very technical level, an executive order is a directive for a federal agency to do something. They are not self executing; they require the agency responsible for implementing them to actually implement them. Executive orders can always be legally challenged in the courts, and Congress has the legal power to override an executive order by writing legislation rendering it moot (although that would require presidential approval, like all laws). However, if the agency tasked with implementing an executive order elects to implement it right away, they certainly can. Unless and until Congress overrides it or a court rules it unconstitutional (or stays the order with an injunction), an executive order that is actively implemented is basically the law.

Q: An executive order is legal if it is "founded on the authority of the President derived from the Constitution or statute.” Is it for the courts exclusively to decide whether the order is constitutional?

Napolio: It is technically the courts' job to declare what is and isn't constitutional. But if majorities in Congress decide they don't like an executive order (on policy or constitutional grounds) they could overturn it. But that would be subject to a presidential veto, so two-thirds majorities in each chamber of Congress are actually necessary to overturn an executive order.

Q: Does Congress have any authority to challenge or override executive orders? If not, can they make it more difficult to execute an order?

Napolio: Yes. Congress has legislative power and a statute supersedes an executive order. Also, if an executive order requires new appropriations to be implemented, only Congress can appropriate those funds. So Congress could choose not to provide enough money to the executive branch to successfully implement an executive order.

Q: The naming of the day one Trump executive orders is provocative. Two examples are: “Ending the Weaponization of the Federal Government,” and “Putting People Over Fish: Stopping Radical Environmentalism to Provide Water to Southern California.” Is this standard for executive orders in presidential administrations?

Napolio: The naming of executive orders is pretty eclectic, although they usually have quite mundane titles. Trump's brand has always been to be flashy or showy, and it shows in his naming of executive orders.

Q: Are some these orders symbolic? Two examples are the order for federal employees to return to full-time work, which includes room for supervisors’ discretion, or the order to direct agency heads to implement “emergency price relief” minus specific direction.

Napolio: Many executive orders certainly have a symbolic component. In politics, the appearance of doing something, or being able to claim credit for having done something, is often as if not more important than actually getting things done. It is very difficult to track whether an executive order was successful at doing what it claims to do, but it is very easy to claim credit for publishing the order and looking like the president is doing something. A new book, "False Front: The Failed Promise of Presidential Power in a Polarized Age," by Kenneth Lowande (University of Michigan) makes this exact argument. The people expect the president to fix lots of problems that they cannot unilaterally fix, but the president is held accountable for failures anyway. Executive orders are a relatively cheap way to make it look like they're doing something to fix problems.

Q: Does the president have the right to unilaterally rename (Mount) Denali and the Gulf of Mexico?

Napolio: Congress empowers the Secretary of the Interior to name US geography (43 USC 364), and Trump's order instructs the interior secretary to rename (Mount) Denali to Mount McKinley, which they certainly can do. They can also rename the Gulf of Mexico for official U.S. documents, but cannot compel other countries to use the same nomenclature.

Q: Can the president withdraw from the World Health Organization and the Paris Agreement without challenge?

Napolio: Not without challenge. There's debate about whether Trump would need congressional approval to withdraw or whether he can do it unilaterally.