As a kid, she only got one pair of new shoes a year.

It was all Elvera Madlene “Dollie” Totaro Wolverton’s father could afford for each of the five kids he supported at one point. What was abundant was the love and care they received. It’s one of the many memories Wolverton carries with her and likely one that cemented her spirit of giving.

Born in Detroit, Michigan in 1936, Wolverton’s family moved to Pomona, California, when she was a child. After spinal meningitis took the lives of her two older sisters as toddlers, Wolverton’s arrival to the family was received with much love and joy, especially by her parents and two older brothers.

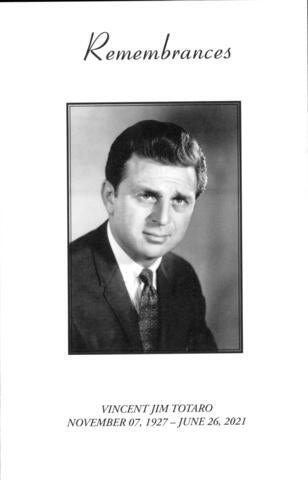

Finances were tight for the immigrant Italian family, so Wolverton’s brother, Vincenzo Jim Totaro, dropped out of school at age 13 and went straight to work. His sacrifice meant Wolverton could focus on school instead of working herself. Wolverton transferred from Chaffey College to UC Riverside, then the newest UC campus. She majored in history and graduated from UCR in 1957, celebrating with a class of 62 Highlanders who took courses in five buildings surrounded by rural landscapes and where sidewalks were nonexistent, she recalls.

“I was a first-generation student — not only the first in my family but also the first among an enclave of other Italian families. Eighteen elders came to see me graduate from UCR and I came to understand how much it meant not only to my family but also to others,” Wolverton said. “By going to UCR I wanted to be a doctor, but my father said no because it meant I would see men without clothes on. Instead, he said I could become a teacher.”

Wolverton burst into laughter at the memory of her father’s rationale. As an educator, she put her heart into creating opportunities for children and youth.

After earning a master’s in elementary school administration and curriculum development at Cal State Long Beach and certification in early childhood at UCLA, Wolverton worked as a teacher and elementary school administrator. Then, in 1965, with the launch of the national “War on Poverty” by then-United States President Lyndon B. Johnson, her career in education and activism got underway. She became the director of Riverside County’s Head Start initiative, implementing programs in 28 communities, including migrant settings, Native American Reservations, and establishing career development programs with college credit for teacher aides and other staff positions.

After three years, she got a job with the California Department of Education in Sacramento as an early childhood specialist, overlapping with the arrival of State Chief School Officer Wilson C. Riles, the first African American elected to a statewide office in California. Riles gave her a piece of advice she followed closely.

“In 1970, as I prepared to go to Washington, D.C. to work, Wilson Riles counseled me about many things and told me, ‘Choose carefully the hills you’re willing to die on,’” Wolverton recalls.

Wolverton worked in federal service for 36 years, spanning the administrations of seven presidents, from Richard Nixon to George W. Bush.

Knowing the pivotal role higher education had in her own life and as a means of thanking her brother, Vincenzo Jim Totaro, Wolverton established a $500,000 scholarship endowment in his name. Scholarships will be awarded to first-generation students at UCR. Recipients who continue to meet requirements will continue to receive annual awards until the completion of their undergraduate degree, up to four years for freshman recipients and two years for recipients who have transferred from a community college.

“I always think of my brother Jim because he sacrificed so much. He gave up school to help our family, he brought in a $4 weekly paycheck,” said Wolverton, whose eyes swell with tears from the memory. “I got to attend college because of his sacrifice, this is the least I can do to honor him.”

As she grew up both in Detroit and in the Inland Empire, Wolverton said she learned important lessons: Don’t be afraid. Speak up to make a difference. Help others. Be grateful.

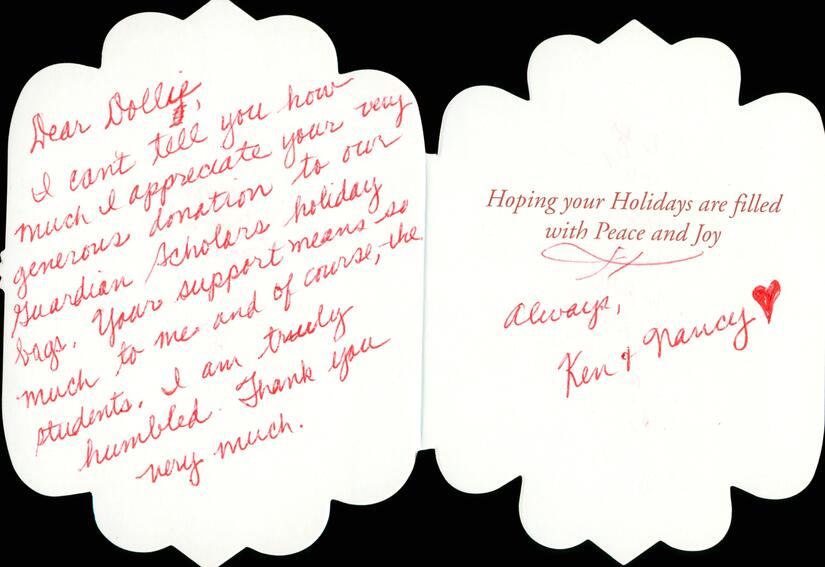

Those lessons became a roadmap not only for her career as an educator but also her contributions as a volunteer and community activist. At UCR she has been an active alumna since 1992 and has served in various capacities, including 12 years in the UCR Alumni Association Board of Directors. In April 2025, Wolverton will be recognized with the Distinguished Philanthropist Award during the university’s annual Honors Gala.

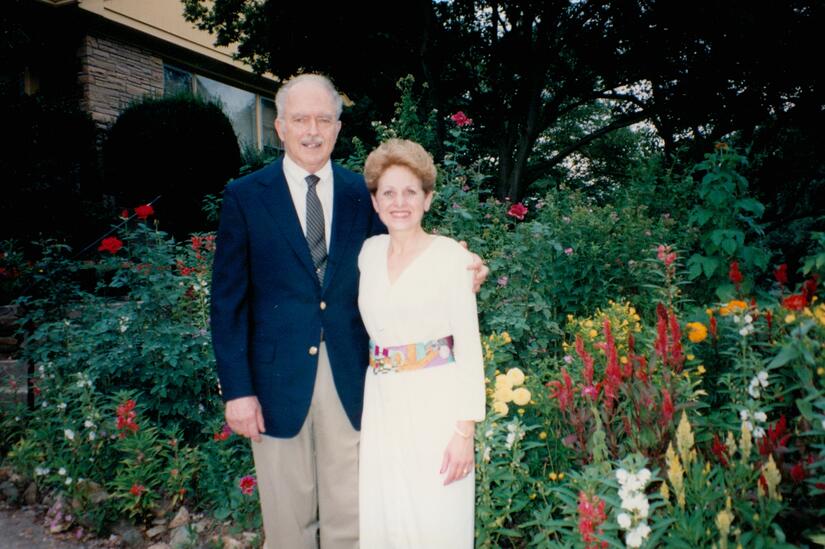

Throughout her career in D.C., Wolverton resided in Maryland with her late husband of 33 years, Sid Wolverton. For decades Wolverton drove with a trunk full of toiletries and hygiene items to give homeless people she encountered on the streets. She also had boxes of brand-new tennis shoes for them.

Other times she spent endless hours at Shepherd’s Table, a Maryland-based homeless shelter and soup kitchen. Sometimes she sorted donated clothes, but her favorite task was serving food because it created space to converse with the men and women who patiently waited in line for their meal. In retirement, she advocated for protecting public land, reuniting siblings separated in foster care, promoting the establishment of libraries in women’s prisons, and funding equestrian therapy for children and adults.

In memory of her husband, an Eagle Scout, she established and funded a six-year program so that Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, and Brownies could play golf for free. She has been on the Majority Council of Emily’s List for 26 years, supporting the election of qualified women at all levels of government.

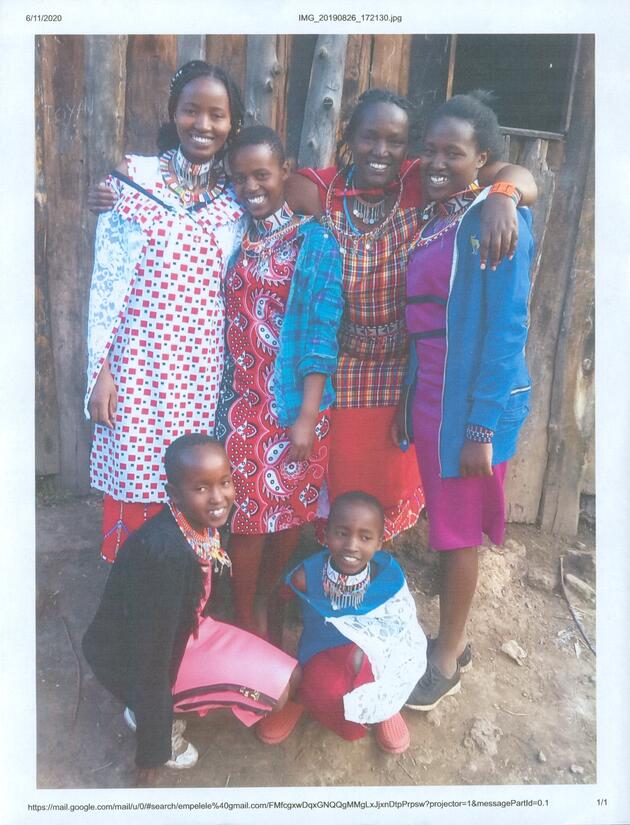

Wolverton’s love for education access goes beyond borders. For the past nine years, through a direct relationship with the family, she has been paying for the education of five young women of the Masai Tribe in Loitokitok, Kenya. Three have completed vocational certification, and the younger two are in boarding school.

With humbleness and matter-of-factly, Wolverton shares these unglorified stories. It’s not an exaggeration to say that her signature smile and constant giggles emit genuine joy.

But why give so much?

“I always had this feeling that I must have been a very wanted child,” Wolverton said. “I received a great deal of love and I’m so pleased that I’ve shared it with others rather than keep it all for myself.”