As the Trump administration reimagines the United States' posture in the three-year-old Russia-Ukraine war, the scholarship of leading imperial Russia scholar and UCR Professor Georg Michels takes on renewed relevance. Michels, a Harvard-trained scholar in Early Modern Russian and Ukrainian History, is currently working on a new book project about Ukrainians' relations with Ottomans, Poles, and Russians during the 17th century, with an interest in the Ottoman Empire's support of Ukrainian resistance against Russian military invasion and occupation. Michels' 2021 book “The Habsburg Empire Under Siege: Ottoman Expansion and Hungarian Revolt in the Age of Grand Vizier Ahmed Köprülü (1661-76)" won the 2021 Hans Rosenberg Prize awarded by the Central European Historical Association. He was co-editor of the 2009 University of Minnesota Press book "Russia’s Dissident Old Believers, 1650-1950." In 1999, he published through Stanford University Press "At War with the Church: Religious Dissent in Seventeenth-Century Russia."

Following is an analysis Michels has penned following recent developments in U.S.-Russia negotiations to end the war:

The future of independent and democratic Ukraine is at stake at this very moment; there is a grim possibility that the U.S. will abandon Ukraine just as Western allies abandoned Czechoslovakia in 1938. The imperial visions of the Kremlin that regard Ukraine as “a non-historical and artificial nation” may very well win out as Russian and U.S. negotiators are meeting in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia to discuss the future of Ukraine.

As so often in its history, Ukraine was not asked to participate in the discussion of its fate. The danger is therefore acute that U.S. negotiators will be convinced by the arsenal of historical myths and fabrications that the Putin regime has used for more than 10 years to justify the invasion of Ukraine and the annexation of Ukrainian territory.

Kremlin narratives about Ukraine and its history have one thing in common: they all deny the legitimacy of Ukraine’s existence. Some of these narratives originated in the 20th century, but most date back to the Middle Ages, when Russian tsars and their ideologists formulated justifications for the west- and southward expansion of what was then still the Principality of Muscovy, a territory far removed from Europe and the Black Sea by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire.

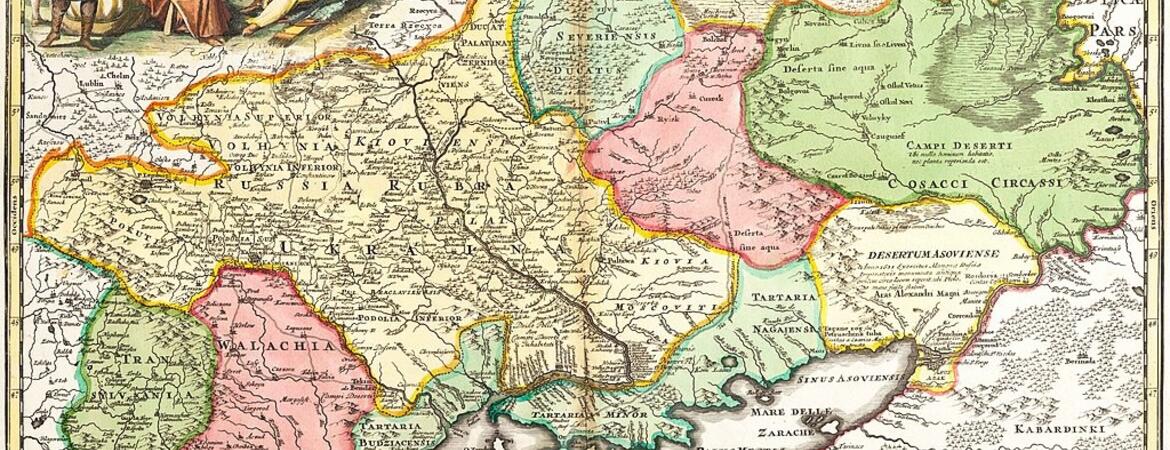

A cursory look at any historical map from the 14th-17th centuries demonstrates that the core lands of modern-day Ukraine were then governed from Warsaw and Vilnius. And modern Ukraine’s southern regions bordering on the Black Sea coast as well as Crimea were largely ruled by the Crimean Khanate, whose leaders were proud descendants of Ghingiz Khan and enjoyed the protection of the Ottoman Empire whose fortresses stretched along the entire Black Sea Coast.

Moscow was far away, and the dream of Russian tsars to rule over Ukrainian lands could only be realized by launching a long series of imperial wars of conquest. Wars with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth lasted more than 300 years and ended only when the Commonwealth ceded Kyiv and the eastern parts of Ukraine to the Kremlin in the Andrusovo Treaty of 1667.

The treaty, which divided Ukraine into a western Polish-occupied and eastern Russian-occupied zone, so outraged Ukrainians that their leaders turned to the Ottoman Empire for protection. The Kremlin then had no choice but to go to war against the then-most powerful empire on earth. And it took more than a century and the lives of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Russian soldiers to destroy the Ottoman presence on Ukrainian lands. The Russo-Ottoman wars culminated in the 1783 annexation of Crimea and the seizure of the last Ottoman fortresses along the northern littoral of the Black Sea during the 1790s.

These were the wars of emergence of the Russian Empire. Muscovy, the once small principality of the east, that few statesmen in Europe had taken seriously, had become a mighty empire. And now that the Ottomans had been pushed out of Ukraine, there was no stopping the Russian advance: the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was next and completely disappeared from the map of Europe in 1795. With the exception of Ukraine’s westernmost region—which Russia ceded to the Habsburgs during the Partitions of Poland—all of Ukraine had become part of the Russian Empire.

Russian nationalists today want us to believe that Ukrainians were only too happy to join their Russian brothers. They claim that Ukrainians never had any national consciousness of their own; rather they have always been “Little Russians” who shared with their “big brothers” a common eastern Christian (Orthodox) identity. This was indeed—and has remained to this day—one of the most powerful mythologies of Kremlin imperialism.

During the 17th century, Russian armies moved repeatedly into the field to rescue the “little Russians” from the double danger of the Catholic Counter-Reformation (that is, the Polish Jesuits) and the archenemy of Christendom, that is, the Muslim Turks. It is true that anti-Catholic and anti-Muslim rhetoric drove some Ukrainians into the Russian camp, but the majority did not budge. Popular uprisings erupted and largely eliminated the Russian presence in Eastern Ukraine.

Triumphant, Ukrainian elites appealed to Istanbul and called for Ottoman protection against the inevitable next Russian invasion. In the late 1660s, the Ottoman sultan recognized Ukraine as an independent and unified state stretching from Vinnytsia in the west to Zaporizzhia in the east.

None of this figures in Russian nationalist narratives. Instead, the focus of most Russians is on the Kremlin’s historical mission to bring back strayed Ukrainians into the fold of Orthodox Christian Russia. In fact, it is again Orthodox messianism that is driving much of the thinking of Putin and the men around him, including those who sit opposite Marco Rubio in Riyadh. Their historical imagination is fixated on the alleged origins of Russian Orthodox religion and church in Kyiv, the capital of the medieval state of Rus’ which was destroyed by the Mongols in 1240. The Rus’ princes, Vikings by origin, had converted to Orthodoxy in 988 and now lie buried in the crypts of Kyiv’s ancient monasteries and churches. Like Russian tsars Putin considers these grave sites to be holy shrines; Kyiv for him is the cradle of Russian civilization.

Not surprisingly, he made a pilgrimage to the relics of his patron saint Vladimir in 2013 to mark the 1,125 year anniversary of Vladimir’s conversion to Orthodox Christianity. Vladimir was none other than the founder of the Kyivan state; Ukrainians call him Volodymyr and medieval sources name him by his Scandinavian name, Waldemar. For Putin, Waldemar was the founder of the first Russian state; the territory of this state needs to be reintegrated into the fabric of today’s Russia. Without it, the national mission of Russia as a torchbearer of true Christianity against a decadent West cannot be fulfilled.

Perhaps it is not coincidental that Ukrainian President Zelensky met with Erdogan, the Turkish president, while the representatives to the Russian and American empires were assembling in Saudi Arabia. Both Erdogan and Zelensky are aware that it was the Ottoman Turkish Empire that once came to Ukraine’s rescue when Russian troops stood poised to conquer the Ukrainian lands for the first time in the late 17th century.

Who will save Ukraine today? This is the question that many Ukrainians and East Europeans (especially Poles) ask themselves. Can Ukraine expect protection from the nationalists of the Trump administration who believe in America’s Christian roots and destiny? They have much in common with Putin and his ilk: they all believe that historical time needs to be reversed and dream of the return to a glorious past. For Ukrainians this imagined glory of past empires may turn into a major historical catastrophe.

Photo from WikiCommons. Cartographer Johann Baptist Hohmann assessed all data about Ukraine to make this map in 1720.