President Donald Trump's implementations and threats of tariffs have created stock market instability, driving talk of a possible recession. We asked Jana Grittersová, a UC Riverside economist and associate professor of political science, to characterize the mindset of investors, and the relevance of various economic indicators. She is a former central banker at the National Bank of Slovakia and an economist at the European Commission, the executive body of the European Union.

How does tariff uncertainty affect investors’ decision-making?

Grittersová: Tariff uncertainty disrupts predictability, making it difficult for firms to forecast corporate earnings, supply chain costs, and global market demand. This uncertainty discourages expansion plans and new hiring. In a volatile tariff environment, investors demand higher returns for holding riskier assets, such as equities, particularly in sectors that rely on international trade. Instead, they shift their investments into defensive stocks, such as utilities or healthcare, as well as safe-haven assets, such as gold. As a result, the S&P 500—a stock market index that tracks the performance of 500 of the largest publicly traded companies in the United States—has declined. At the same time, Europe’s Stoxx 600 (that covers the performance of 600 companies across 17 European countries) has risen by 12% (according to The Economist), driven by a weakening dollar and a surge in European defense stocks driven by expectations of higher defense spending by European countries. Overall, frequent shifts in trade policy contribute to an unstable business environment.

At first, markets seem to bounce back immediately after a pro-trade Trump announcement, such as postponing threatened tariffs. Now, they don’t seem to be bouncing back with good-news pronouncements. How do you interpret investors’ mindset?

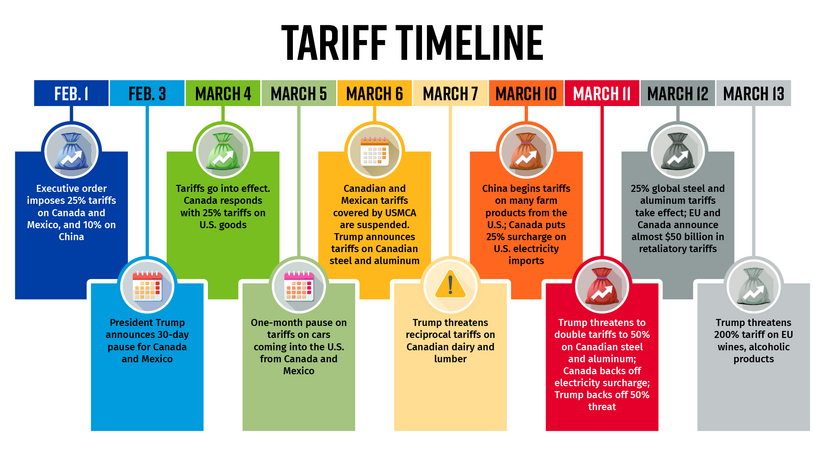

Grittersová: Initially, markets priced in Trump’s protectionist rhetoric as part of a negotiation strategy, but repeated reversals (e.g., tariff threats, exemptions, sudden hikes) have eroded trust. Thus, markets now see concessions as temporary maneuvers rather than resolutions. Markets are no longer just factoring in the direct costs of tariffs; they are also pricing in the risk of retaliatory measures, such as potential EU tariffs on U.S. goods. Early tariff delays (e.g., Canada and Mexico exemptions in February 2025) briefly reassured investors, but Trump’s unpredictable policy reversals have rendered "positive" news short-lived. Stock markets' lukewarm reaction to the March 2025 tariff postponement reflects deepening skepticism about the possibility of de-escalation. Investors are also increasingly wary of a broader economic slowdown due to weakening corporate earnings and disruptions to global trade. For example, Goldman Sachs has lowered its U.S. growth forecast for 2025 by 0.7 percentage points to 1.7% , citing the adverse effects of tariffs and trade policy shifts introduced by the Trump administration.

Does the U.S. have a trade deficit with the rest of the world? Is this deficit necessary, and why?

Grittersová: Yes, the U.S. runs a persistent trade deficit, which means that it imports more goods and services than it exports. The U.S. trade deficit reached a record high of $918.4 billion in 2024, a 17% increase from the previous year. This imbalance is largely driven by the unique role of the U.S. economy: the U.S. dollar serves as the world’s primary reserve currency, creating international demand for U.S. financial assets such as Treasuries, stocks, and real estate. Foreign central banks hold roughly 60% of global reserves in U.S. dollars. This strengthens the dollar, making U.S. exports more expensive and imports cheaper, thus widening the trade deficit.

Additionally, U.S. consumers spend heavily on goods with imported components, such as electronics and apparel. Trump’s tariffs aim to reduce deficits but risk unintended consequences. First, higher import prices raise production costs for domestic firms, limiting the benefits of protectionist policies. Many U.S. companies, especially in the high-tech sector and manufacturing (e.g., iPhones use parts from 43 countries), rely on global supply chains. Tariffs also hurt American farmers, who export about 20% of their total output. Second, retaliatory measures can further increase the trade deficit by reducing demand for U.S. exports. While the trade deficit is not inherently negative—as it reflects the U.S.'s ability to attract foreign investment, finance government debt at lower interest rates, and provide consumers with diverse, competitively priced goods—tariffs can lead to higher consumer prices, reduced global competitiveness for U.S. businesses, and provoke trade disputes, potentially outweighing any intended of addressing trade imbalances.

The so-called fear gauge — the Cboe Volatility Index — shows volatility is increasing but not at red-flag levels. What is the Cboe Volatility Index, and what would cause it to reach red-flag levels? When was the last time it reached red-flag levels?

Grittersová: The Cboe Volatility Index (VIX) tracks expected volatility in the S&P 500 and tends to rise during periods of market uncertainty. Often called the "fear index," it reflects investor demand for hedges against potential market declines. The VIX reached around 25 in March 2025, which indicates elevated market concern but remains below crisis thresholds. In March 2025, the VIX reached approximately 25, signaling heightened market concerns, though still below crisis levels. Historically, the VIX peaked near 80 during the 2008 financial crisis, and values above 40 typically indicate severe systemic shocks, such as bank failures or the 2020 COVID-19 market collapse. Current risks that could drive the VIX higher include escalating trade tensions with the European Union and China, combined with supply chain disruptions in sectors like car manufacturing.

The U.S. Consumer Sentiment Index has fallen to a two-year low, to 57.9 percent. What does this represent, and foretell, in terms of peoples’ willingness to spend?

Grittersová: The U.S. consumer sentiment index has indeed fallen to a two-year low of 57.9 in March 2025, according to the University of Michigan's Consumer Sentiment Index. This represents growing pessimism among consumers about the economy. The decline is attributed to various factors, including concerns about President Trump's tariff policies, rising inflation expectations, and overall economic uncertainty. Despite low sentiment, consumer spending has remained resilient, especially among high-income households. However, lower-income consumers are facing more significant challenges, with housing costs consuming nearly half of their disposable income. Continued pessimism could eventually lead to reduced discretionary spending, particularly on travel, homes, and cars. The impact of tariffs is concerning, as their cost is ultimately borne by American consumers through higher prices on both imports and competing domestic goods.

What are the economic indicators that will be most telling to watch in the time ahead?

Grittersová: Several key economic indicators will be important in assessing potential economic problems. The Consumer Sentiment Index (currently at a two-year low of 57.9) will be a critical barometer of public confidence and spending behavior. Inflation expectations, both short-term (currently at 4.9% for the year ahead), influence consumer behavior and Federal Reserve policy decisions. The GDP growth rate is also an important indicator, with recent projections indicating potential negative growth for the first quarter of 2025, raising concerns about overall economic health. The yield curve, a historically reliable recession predictor, remains flat but has shown signs of inversion in recent months - a pattern that has preceded every U.S. recession in the past five decades. Rising tariffs and protectionist trade policies drive up costs for businesses and consumers, fueling inflationary pressures and slowing global trade.

Header image: Katrina.Tuliao, via Wikimedia Commons.