A newly described fossil reveals that leeches are at least 200 million years older than scientists previously thought, and that their earliest ancestors may have feasted not on blood, but on smaller marine creatures.

“This is the only body fossil we’ve ever found of this entire group,” said Karma Nanglu, a paleontologist with the University of California, Riverside. He collaborated with researchers from the University of Toronto, University of São Paulo, and Ohio State University on a paper describing the fossil, which is now published in PeerJ.

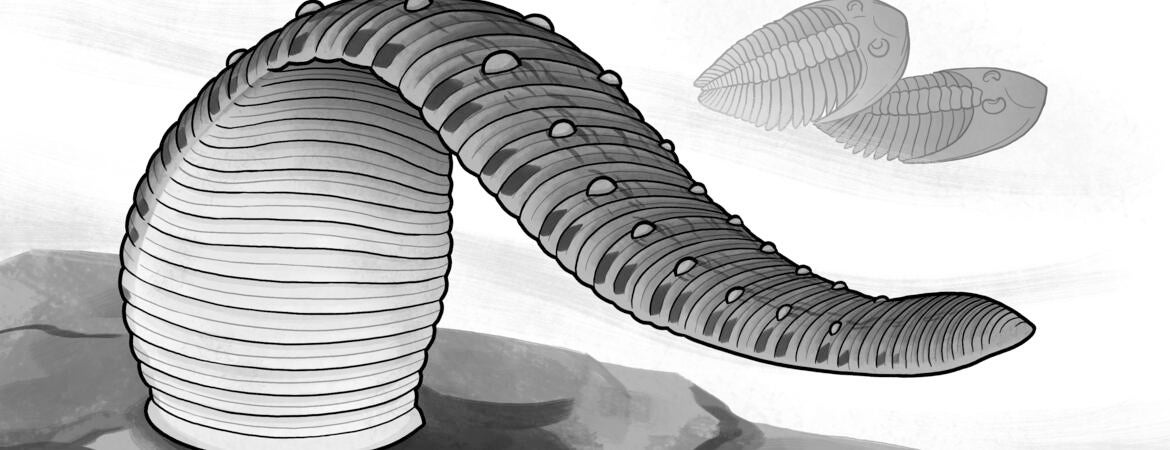

Roughly 430 million years old, the fossil includes a large tail sucker — a feature still found in modern leeches — along with a segmented, teardrop-shaped body. But one important feature isn’t found in this fossil: the forward sucker that many of today’s leeches use to pierce skin and draw blood.

This absence, along with the fossil’s marine origin, suggests a very different early lifestyle for the group known as Hirudinida. Rather than sucking blood from mammals, reptiles, and other vertebrates, the earliest leeches may have roamed the oceans, consuming soft-bodied invertebrates whole or feeding on their internal fluids.

“Blood feeding takes a lot of specialized machinery,” Nanglu said. “Anticoagulants, mouthparts, and digestive enzymes are complex adaptations. It makes more sense that early leeches were swallowing prey whole or maybe drinking the internal fluids of small, soft-bodied marine animals.”

Previously, scientists believed leeches emerged about 150–200 million years ago. That timeline has now been pushed back by at least 200 million years, thanks to the fossil found in the Waukesha biota, a geological formation in Wisconsin known for preserving the bodies of soft tissue animals that usually decay before fossilization.

Preserving a leech fossil is no small feat. Leeches lack bones, shells, or exoskeletons that are most easily preserved over millions of years. Fossils like this require exceptional circumstances to preserve, often involving near-immediate burial, a low-oxygen environment, and unusual geochemical conditions.

“A rare animal and just the right environment to fossilize it — it’s like hitting the lottery twice,” Nanglu said.

The fossil came to light during a broader study of the Waukesha site by researchers at Ohio State University, who are co-authors on this paper. Though initially unrecognized for what it was, the specimen caught Nanglu’s eye during the early pandemic years.

He consulted with leech specialists, including lead author Danielle de Carle of the University of Toronto, and the group worked together to confirm its identity. They were ultimately convinced they’d found a leech because of the tail sucker and the clear body segmentation, which is a combination only found in leeches.

Today’s leeches are found in freshwater, saltwater, and even on land. Their feeding behaviors are equally diverse, from scavenging to predation to parasitic blood feeding. But understanding their origin has been difficult because soft-bodied animals rarely leave fossils.

Nanglu, who studies creatures rarely found in the fossil record, said the find is part of a larger effort to trace the early history of complex life, and to challenge assumptions about the past.

“We don’t know nearly as much as we think we do,” he said. “This paper is a reminder that the tree of life has deep roots, and we’re just beginning to map them.”

“It’s a beautiful specimen,” Nanglu added. “And it’s telling us something we didn’t expect.”