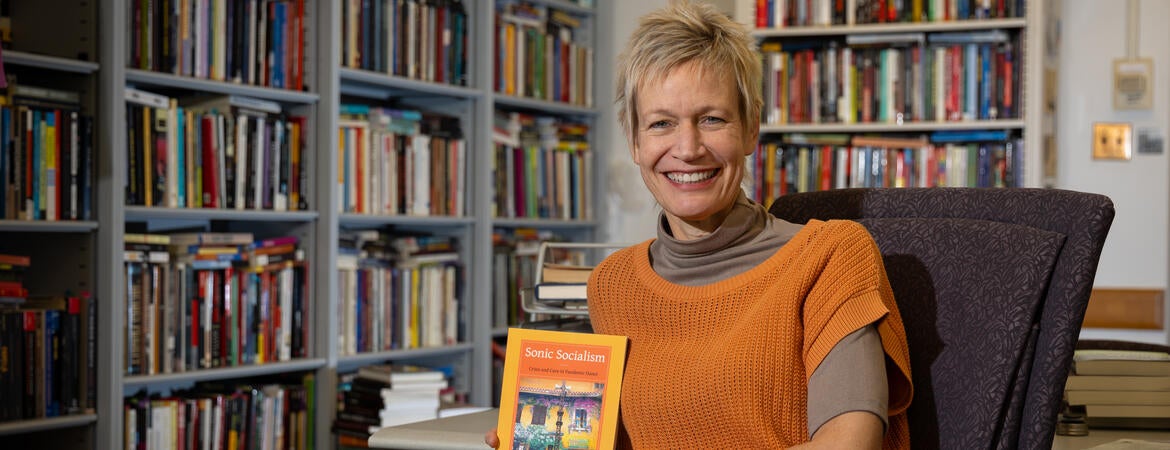

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Vietnam’s response stood out globally, not just for its low infection and death rates, but for how it mobilized sound as a tool of public health. In her book “Sonic Socialism: Crisis and Care in Pandemic Hanoi” (University of California Press, 2025), Christina Schwenkel, a professor of anthropology at the University of California, Riverside, explores how the Vietnamese government used both old and new media technologies to inform, regulate, and connect people during the pandemic.

In the open-access book, through what she calls “soundwork” and sensory autoethnography, Schwenkel explains how sonic interventions like loudspeakers, messaging alerts, and public health videos not only shaped public health outcomes in Vietnam but also reconfigured how people related to each other and the state.

“At the center of this response were two main technologies: the cell phone and the loudspeaker,” Schwenkel said. “The state sent out billions of text messages with updates about restrictions, health guidelines, and school closures. But the loudspeaker — a technology dating back decades — remained essential, especially for reaching older generations and rural populations less likely to use smartphones. These coexisting systems created a layered soundscape of governance, blending the analog and the digital.”

Schwenkel acknowledged there is a generational divide in media preferences, with younger people tending to prefer texts or online updates, while older people value the collective experience of loudspeaker broadcasts.

“This echoes the kind of cultural listening practices that have deep roots in Vietnam, like groups of elderly men gathering around a shared radio in the morning or whole villages attending mobile film screenings,” she said. “Collective listening still holds a kind of social and emotional resonance.”

According to Schwenkel, sound, as a sensory modality, offers something that sight alone cannot. During lockdowns in Hanoi, she conducted soundwalks — walking through neighborhoods while listening closely to the ambient sounds of life returning, like distant aerobics music or quiet conversations. These auditory cues revealed to her how people were subtly resisting lockdown rules.

“It’s what I call ‘sonic dissent,’” she said. “You could hear parties, construction, and other forbidden activities before you could see them.”

Her research led her to the concept of sonic governance: the use of sound — texts, loudspeakers, public songs — as a means of governing behavior, sharing information, and building collective responsibility. While this can include propaganda, in Vietnam’s case, it often took the form of practical and lifesaving information. For example, the government produced catchy public health music videos that went viral internationally, even airing on shows like Jimmy Kimmel Live.

“Vietnam’s success wasn’t because of sound alone, but sound played a critical role in informing and mobilizing the public quickly,” Schwenkel said. “What the United States often lacks in emergency communication — say, during wildfires or floods — Vietnam handled swiftly and centrally. I call this ‘disaster socialism,’ where rapid, collective mobilization is made possible through centralized infrastructure, including sonic media.”

Post-pandemic, Schwenkel continues to consider what role sound might play in fostering care. She explained that in Vietnam, there’s an ongoing debate about whether to deactivate the loudspeaker systems or keep them for future emergencies. The key, she said, may lie in maintaining adaptable communication systems that can be activated quickly when needed — combining trust, coordination, and a commitment to collective well-being.

This broader understanding of sound’s role in public life also shaped Schwenkel’s approach to teaching, inspiring new ways to connect students with the past and present through listening. During her Fulbright scholarship in Vietnam in 2023–2024, she applied this approach in courses for undergraduates at the National University in Ho Chi Minh City, exploring topics such as “medical listening.”

“I now integrate sound into all my classes,” she said. “I ask students to close their eyes and listen to wartime recordings or urban soundscapes. It helps them engage with history and humanity through a different sensory lens.”

Schwenkel hopes readers of her book walk away with a deeper respect for Vietnam, not as a relic of war or a place in need of Western instruction, but as a nation that has something to teach the world.

“The pandemic revealed how deeply human survival depends on mutual care, clear communication, and community mobilization,” she said. “And sometimes, it all begins with sound.”

Header image credit: Stan Lim, UC Riverside.