Using robotic fins, researchers at the University of California, Riverside have learned how stingrays are able to swim with impressive control. These insights could help underwater vehicles avoid disastrous ground collisions.

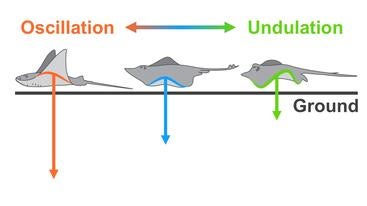

In the wild, rays fall into two broad camps: pelagic, like manta rays, soaring far above the ocean floor, and benthic, like stingrays, hugging the seabed. Their swimming styles reflect their habitats. Pelagic rays flap their fins in a smooth, bird-like motion. Benthic rays undulate with the motion of the waves.

Yuanhang Zhu, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at UCR, suspected these distinctions weren’t just aesthetic. He and his colleagues believed the variations were tied to swimming stability and, by extension, survival.

To explore this, Zhu and collaborators built a robotic fin that mimics ray movement. They tested it in a large water tunnel that simulates ocean flow, measuring how different swimming motions affect lift, which is the force that either helps the fish stay level or pulls it toward the seafloor.

What they found surprised them. Near the seafloor, rays experienced negative lift, that is, being sucked downward. This effect is the opposite of what birds experience when flying steadily near the ground. That difference, the researchers believe, is due to the dynamic way rays oscillate their fins, a phenomenon they describe as an “unsteady ground effect.”

Birds and airplanes hold their wings steady and benefit from a cushion of air beneath them. Rays, in contrast, constantly move their fins, which alters the physics.

"There are many reasons that rays might swim differently near the seabed that are unrelated to lift and thrust, so we weren't sure whether we'd measure any differences between the swimming styles," said Daniel Quinn, paper co-author and associate professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Virginia. "But the results were striking."

“This wasn’t what we expected,” Zhu said. “Instead of gaining extra lift near the ground, the rays were pulled downward. But nature seems to have already solved the problem.”

Indeed, real rays swim with a slight upward tilt. When the researchers adjusted the robot’s fin angle by just a few degrees, the negative lift disappeared. “It’s a small change with a big effect,” Zhu said.

The team also discovered that rays using undulatory, wave-like swimming had better ground clearance than those with purely oscillatory, flapping motions, mirroring how benthic rays navigate tight spaces on the seafloor. In a simulation, when the robotic swimmer was released near the tunnel’s bottom, those using undulatory motions stayed level longer, while oscillatory swimmers crashed into the ground faster.

These findings, published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, suggest that rays’ differing swimming styles are evolutionary strategies to maintain stability in their respective environments.

Zhu envisions a future where bio-inspired robots can toggle between swimming styles. A robot might glide like a manta ray in open water, then shift to a stingray’s undulations when approaching the ocean floor, shifts that would aid marine exploration, surveillance, or environmental monitoring.

Critically, mirroring stingrays’ ability to stay level at low altitudes can help underwater vehicles avoid catastrophic collisions with the ocean floor. Unintended impact, even momentary ones, can disable sensors, snap off fins, or stir up sediment that blinds onboard cameras. In underwater missions where stealth matters, staying a few inches off the seafloor can be the difference between success and failure.

"The results from this project help us think about why benthic rays may swim differently, and may also guide the design of ray-inspired robots that could be used to, say, map the ocean floor," Quinn said.

For this project, Zhu also collaborated with researchers from Lehigh University and Iowa State University. The project was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Office of Naval Research.

More broadly, Zhu’s lab studies propulsion inspired by biology. “Usually, human-made robots cannot both swim in the middle of the ocean, and maneuver easily near the ground,” Zhu said. “But, by watching how rays adjust between undulation and oscillation, we understand now how it is possible.”

(Stingray cover image: Charlotte Bleijenberg/iStock/Getty)