As aging populations and rising diabetes rates drive an increase in chronic wounds, more patients face the risk of amputations. UC Riverside researchers have developed an oxygen-delivering gel capable of healing injuries that might otherwise progress to limb loss.

Injuries that fail to heal for more than a month are considered chronic wounds. They affect an estimated 12 million people annually worldwide, and around 4.5 million in the U.S. Of these, about one in five patients will ultimately require a life-altering amputation.

The new gel, tested in animal models, targets what researchers believe is a root cause of many chronic wounds: a lack of oxygen in the deepest layers of the damaged tissue. Without sufficient oxygen, wounds languish in a prolonged state of inflammation, allowing bacteria to flourish and tissue to deteriorate rather than regenerate.

“Chronic wounds don’t heal by themselves,” said Iman Noshadi, UCR associate professor of bioengineering who led the research team. “There are four stages to healing chronic wounds: inflammation, vascularization where tissue starts making blood vessels, remodeling, and regeneration or healing. In any of these stages, lack of a stable, consistent oxygen supply is a big problem,” he said.

When oxygen from the air or bloodstream cannot penetrate far enough into injured tissue the result is hypoxia, which derails normal healing. The researchers’ approach to preventing hypoxia with a gel is detailed in a paper published in Nature Communications Materials.

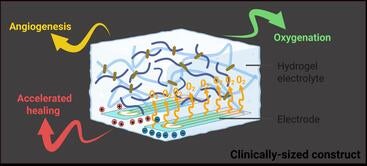

The soft, flexible gel contains water as well as a choline-based liquid that is antibacterial, nontoxic, and biocompatible. When paired with a small battery similar to those used in hearing aids, the gel becomes a tiny electrochemical machine splitting water molecules to generate a slow, steady stream of oxygen.

Unlike treatments that deliver oxygen only at the surface, the gel conforms to the unique shape of each wound, filling crevices where oxygen levels are often lowest and infection risk is highest. Before it sets, the material molds precisely to the contours of the damaged tissue.

Equally important, the oxygen delivery is continuous. Vascularization can take weeks, so brief bursts of oxygen are not enough. The new system can provide sustained oxygen levels for up to a month, helping transform a nonhealing wound into one that behaves like a normal injury.

In tests on diabetic and older mice, chosen because their wounds closely resemble chronic wounds in older humans, untreated injuries failed to heal and were often fatal. With the oxygen-generating patch applied and replaced weekly, wounds closed in about 23 days, and the animals survived.

“We could make this patch as a product where the gel may need to be renewed periodically,” said Prince David Okoro, UCR bioengineering doctoral candidate in Noshadi’s lab and paper co-author.

The gel’s chemistry offers an added benefit. Choline, a key component, has properties that help modulate the immune system and calm excessive inflammation. Chronic wounds are often overwhelmed by reactive oxygen species, which are unstable molecules that damage cells and prolong inflammation. By increasing stable oxygen while helping rein in this immune overreaction, the gel restores balance rather than triggering further stress.

“There are bandages that absorb fluid, and some that release antimicrobial agents,” said Okoro. “But none of them really address hypoxia, which is the fundamental problem. We’re tackling that directly.”

The implications of this project extend beyond wound care. Oxygen and nutrient deprivations are major challenges in attempts to grow replacement tissues or organs, which is one of the primary goals of the Noshadi laboratory.

“When the thickness of a tissue increases, it’s hard to diffuse that tissue with what it needs, so cells start dying,” Noshadi said. “This project can be seen as a bridge to creating and sustaining larger organs for people in need of them.”

There are some factors causing the prevalence of chronic wounds that cannot be solved with a gel. In addition to climbing rates of diabetes and aging populations, UCR bioengineer and paper co-author Baishali Kanjilal notes other factors.

“Our sedentary lifestyles are causing our immune responses to decrease,” she said. “It’s hard to get to societal roots of our problems. But this innovation represents a chance to reduce amputations, improve quality of life, and give the body what it needs to heal itself.”

(Cover image: Fat Camera/iStock/Getty)