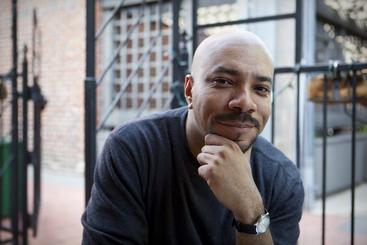

Despite growing up in what he described as a “financially challenged” home in rural Mississippi, John Jennings never wanted for books.

The son of a mother who majored in literature and passed along her passion for fantasy and mythology, Jennings has fond memories of devouring the works of Edgar Allen Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne before moving on to those of Stephen King and Clive Barker.

Now a professor in the media and cultural studies department at the University of California, Riverside, he continues to stoke his interest in speculative fiction, a subset of literature that encompasses fantasy, science fiction, and horror, among other genres.

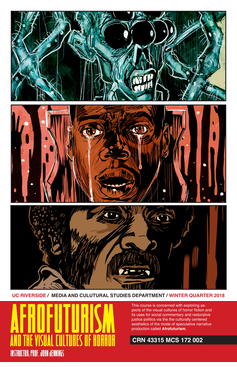

At the start of the winter quarter, Jennings launched a pair of courses that approach two forms of contemporary media — horror films and comic books — from the perspective of Afrofuturism. In the vein of speculative fiction, Afrofuturism draws on fantastical elements to explore the black experience in the wake of the African diaspora, often pointing toward a more hopeful future.

The courses, “Afrofuturism and the Visual Cultures of Horror” and “Afrofuturism and Comics,” are part of a battery of classes Jennings is developing to support the College of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences’ science fiction minor.

When discussing the courses’ origins, Jennings referred to his Southern childhood. Perhaps the most influential figure in his life, his mother, is a lifelong fan of horror films, he explained, and the two would often have lengthy, cathartic discussions about what scared them and why.

He suspects his maternal grandmother practiced rootwork, a strain of folk magic common in Southern states.

Jennings also started reading comic books at a young age — “Casper the Friendly Ghost” being among the first — and said he still cringes at the memory of “an early and horrible attempt at drawing Thor” on one of his mother’s Otis Redding LPs.

His dedication to comic books eventually led to a career in the visual arts. In addition to publishing his own original creations, several years ago Jennings began work on illustrations for a graphic novel adaptation of Octavia Butler’s classic Afrofuturist novel “Kindred,” released in 1979.

Produced in partnership with collaborator Damian Duffy, the adaptation debuted in January 2017, just one month ahead of the film that ultimately inspired “Afrofuturism and the Visual Cultures of Horror”: Jordan Peele’s Oscar-nominated directorial debut, “Get Out.”

“Once I saw ‘Get Out,’ I knew I wanted to teach a class about it,” Jennings said. “It really resonated with me because I’m so fascinated by how speculative fiction deals with social issues.”

The film, Jennings explained, was evocative of the “ethnogothic,” a term he helped coin to refer to the idea of using horror, supernatural, or gothic themes to examine issues around racialized trauma and discrimination.

Building on the idea of the black experience as “haunted” by the weight of centuries of historical violence, “Afrofuturism and the Visual Cultures of Horror” incorporates screenings and seminar-style discussions of 14 short and feature films. The selection runs the gamut from “Sugar Hill” (1994) to “White Zombie” (1932) to “Candyman” (1992).

The goal, Jennings said, is to highlight usages of a variety of horror tropes — think ghost stories and restorative justice narratives — and introduce students to the complicated legacies of ones they might already be more familiar with.

“I didn’t realize, for example, that a lot of people don’t know the different types of zombies,” Jennings said. “We have the original zombies that were generated hundreds of years ago by Haitian vodou, all the way up to the zombies we see nowadays in ‘The Walking Dead.’”

In lieu of a traditional final exam, students will map out their own versions of the “sunken place,” the space of psychological imprisonment navigated by the protagonist in “Get Out” while under hypnosis. According to the course’s syllabus, students are expected to create “a manifestation of their racialized fears or things that they find unsettling around race and its visualization” through video, collage, or any other mode of image making.

Jennings hopes his students leave the class with a stronger appreciation for horror as a technology that gives audiences the opportunity to come to terms with fears that aren’t always namable.

“Going to see a horror movie in a controlled space isn’t unlike riding a roller coaster,” he said. “These movies give us monsters we can defeat, and I think we like that. You look at a film like ‘The Babadook,’ and essentially it’s a monster movie about grief or loss.

“George Romero’s ‘Dawn of the Dead’ is a story about consumer culture and mindless consumption, which is why it takes place in a shopping mall. And ‘Get Out’ is about societal fears, mainly the fear of the other. In all these cases, the monster is the medium.”

Going forward, Jennings expects to see more and more horror movies hit the big screen for two key reasons: They’re relatively budget-friendly to make — by Hollywood standards, at least — and their popularity tends to spike alongside increases in social and political turmoil.

“We’re under a lot of stress right now as a country, and after tumultuous moments in time you usually see an uptick in horror films,” he explained. “We saw this after World War II and after 9/11, and we’re seeing it now in our post-2016 election era.”

Still, for seasoned horror fans like Jennings and his mother, the supposed horror “boom” feels more like an everyday occurrence.

As for her thoughts on “Get Out”?

“She thought it was great,” Jennings said. “Just absolutely great.”