Understanding American history is a challenge, but what happens when some of that history is scattered, inaccessible, and in another language? Steven Hackel, a professor of history at the University of California, Riverside, knows these obstacles all too well.

Hackel was recently awarded an archival grant by the John Randolph Haynes Foundation to continue his work with The Pobladores Project Database, which aims to provide a greater understanding of the non-American Indian population in colonial California through 1850. Hackel, who described himself as being “very fortunate” to receive the award, noted the funding will also help establish an online presence for the database.

Throughout his 25-year research and writing career, Hackel has focused on the history of Spanish colonial California; the influence of Father Junípero Serra, the canonized Franciscan priest who initiated the system of California missions; and colonial North America. His research reveals the complexity of Spanish colonization in North America, a broad segment of American history that’s embedded in non-English sources — that is, ones that don’t begin in the original 13 English colonies of the East Coast.

“The history of Spain in North America, the history of Native Americans in North America, is a much deeper and longer history than is typically included in the national narrative of American History,” Hackel said. “And we have a very important history here in California.”

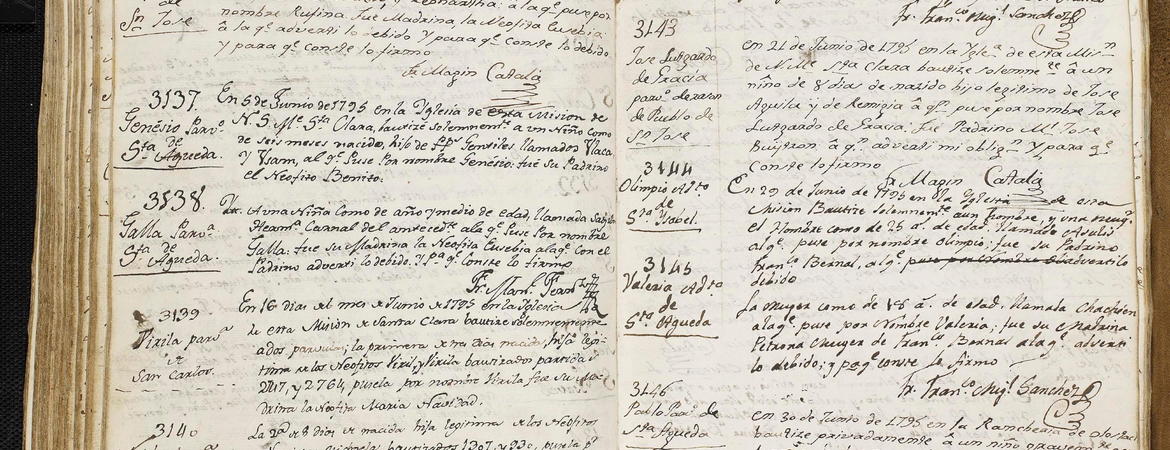

Hackel first sought to shed light on connections between the two by creating an earlier database called the Early California Population Project, or ECPP. Under the auspices of the San Marino-based Huntington Library, he developed the database between 1998 and 2006 to address the need for a comprehensive, accessible collection of information on California Indians and early settlers through 1850. Hackel, who served as general editor for the project while teaching at Oregon State University, led the consolidation of baptismal, marriage, and burial records spanning from 1769 to 1850.

But that effort yielded only “momentary views of non-Indians” and revealed the need for an additional database that could capture important demographic information on other populations.

“We had just the vaguest of sketchy impressions of the immigrants to California before 1850, but not a social-scientific understanding of who they were and how their communities were formed,” Hackel explained.

His current effort, The Pobladores Project Database, is intended to complement the ECPP. The database, the construction of which Hackel commenced in 2009, is named for the settlers and soldiers from Spain and Mexico who lived in California between 1769 and 1850.

Though the lineages of many contemporary residents of Los Angeles can be traced back to these early settlers and soldiers, little is known about them. Hackel found that existing research couldn’t answer fact-based questions about, for example, lifespan, familial relations, and geographic moves.

It should come as no surprise, he added, that both researchers and the general public lack an understanding of how these early groups fit into the larger context of American history.

Part of the challenge of making such groups’ histories more visible stems from the complexity of transcribing their original records. A bulk of the data is contained in documents from the California missions, whose records use language and abbreviations that make transcription a tedious process. Even gaining access to such records can be difficult, as their fragility and age complicate their conservation. Still, Hackel saw the potential in establishing the new database.

“We can make some very important and powerful comparisons between colonial Los Angeles and other regions, and other places that Spain settled in the early period,” he said. But in order to do so, that information first has to be collected, verified, and made available.

Under Hackel’s direction, two graduate student researchers in UCR’s history department, Kristen Hayashi and Evan Suda, are working this year to add to the database the information from the California mission records, the Los Angeles censuses of 1836 and 1844, and microfilm copies from various regional archives. To date, the project has sourced information on some 14,000 individuals.

By giving a fuller sociocultural understanding of early Los Angeles and its immigrant communities, Hackel hopes this database will “answer the most basic questions” in a non-genealogical format by asking different types of questions than existing research already has.

“We need to start sort of from the bottom — the building blocks for a new way of understanding early California history,” Hackel said. “This database will be a foundation for generations of new research.”