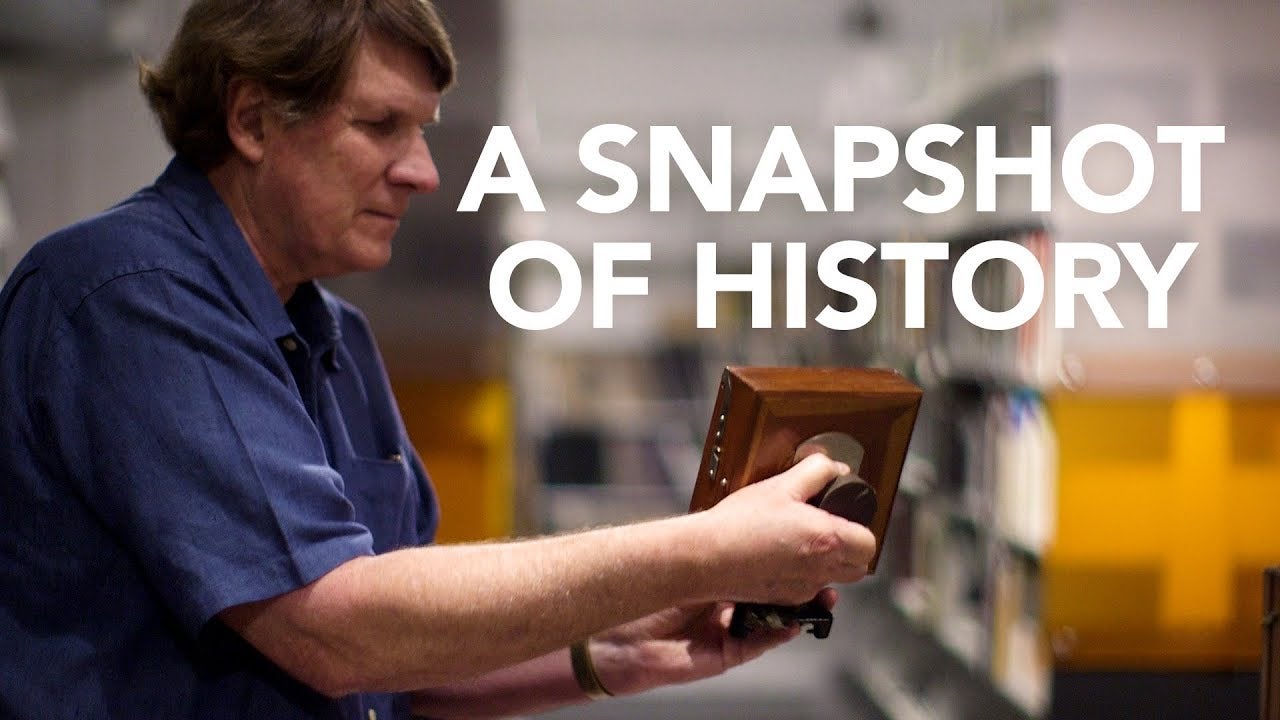

The California Museum of Photography has received a robust donation of American field view cameras, filling a significant gap in the museum’s collection. Donor Larry Pierce, a mineralogist and majority owner of Phoenix-based Fiberquant Analytical Services, gifted his collection of more than 500 cameras, as well as hundreds of related accessories and original catalogs amassed over the last 40 years.

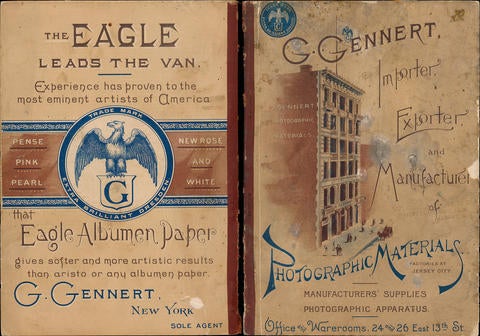

Primarily constructed of wood and brass, the collection includes cameras produced between 1850 and 1930 by American manufactures including Scovill Manufacturing Company, The E. & H.T. Anthony Companies, The George Eastman Companies, and others. Almost every field camera in the collection is a different model, ranging in size from 3-by-4 to 14-by-17 inches, and nearly half of the cameras include their original cases. Made prior to the mass production and standardization of related parts, the cameras represent a vast array of styles, components, and numerous corresponding patents that trace the evolution of field camera design.

“This collection is unique in how well researched it is, and how detailed and nuanced it is,” said Leigh Gleason, director of collections at UCR ARTS. “We have American field cameras in our collection, but nowhere near the numbers Larry had collected or the variety and differences that he has accumulated.”

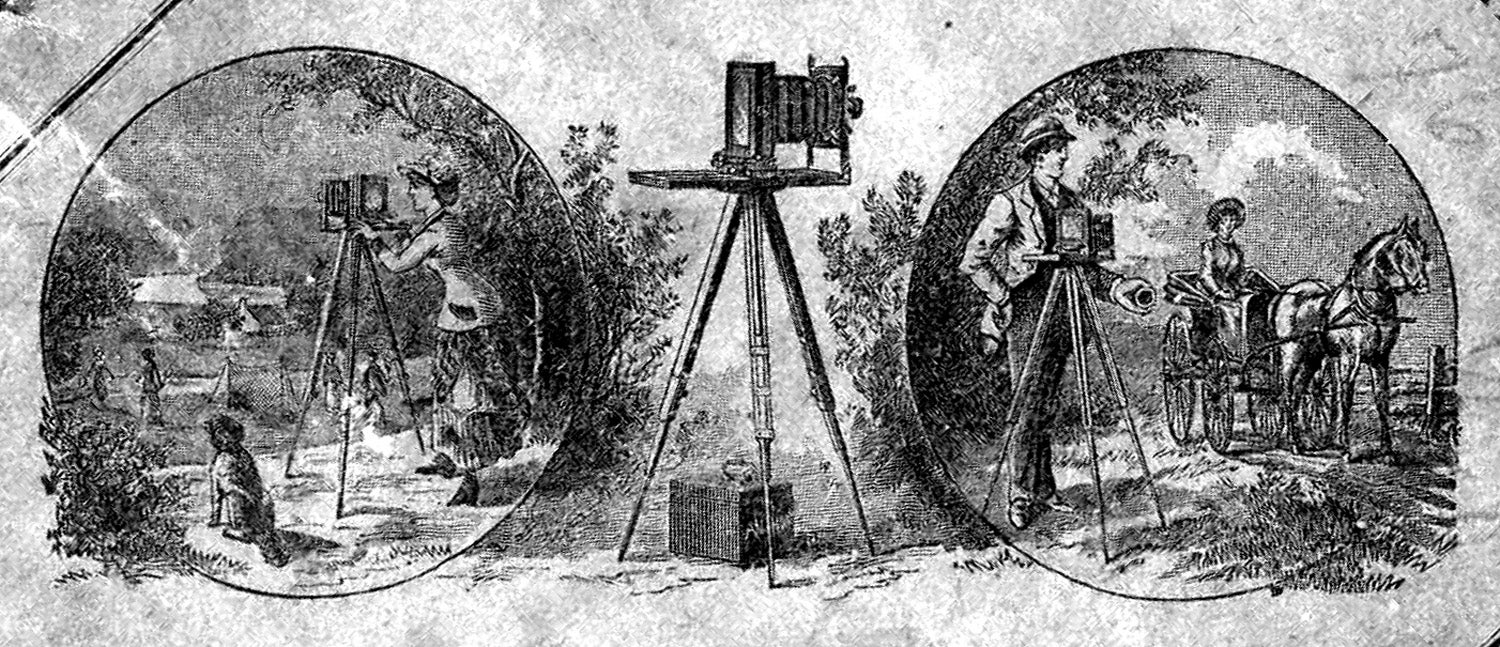

Field cameras play a significant part in the history of photography and proliferation of photographic images in early America. Unlike earlier camera models made entirely of wood, field cameras consisted of wood frames separated by bellows, which made it possible to fold the cameras into compact and portable sizes. This allowed the cameras to be taken into the “field,” where they were used to document major historic events such as the U.S. Civil War, presidential campaigns, and travels through the American West.

“These cameras represent some of the earliest access that everyday people had to photography,” Gleason said. “They predate, for example, when the Kodak Brownie came out, which is often pointed to as the early point, but this is really the start of everyday photography. They produced images that allowed people to collect pictures of America, so our own photographic history is told through these cameras.”

Although field cameras made photography more accessible to the masses, the process of generating photographs required both skill and significant disposable income, making it an endeavor primarily reserved for the middle class.

“There was no such thing as a snapshot at that time,” Pierce said. “It was the horse and buggy era, so people would take whole-day outings. They took these cameras with them but had a limited number of plates, so they would only be able to take between two and 10 pictures in total. When they got home, they had to personally develop and print them. It was a heavy hobby and it was also an expensive hobby.”

Pierce recalls being interested in photography from an early age, but it wasn’t until graduate school in the 1970s that he began collecting wood and brass cameras.

“I didn’t have two nickels to rub together through college or most of graduate school, but when I was in Tempe at Arizona State University, I walked into a photography store one day, and they had one of these old wood and brass field cameras sitting up on a shelf,” Pierce said, noting he had to convince the owner to sell it to him. “That was the first camera I had. I had no idea these things were available for private purchase. I assumed that they were all in museums, but I just liked the look of them, the wood and brass. It was just a beautiful manufactured item from the 1890s.”

Pierce continued adding to his collection by attending shows held by the Western Photographic Collectors Association in Pasadena, scouring for rare models. In later years, the advent of eBay brought more cameras out of attics and basements, making it easier for Pierce to locate field cameras and grow his collection.

“I definitely feel a history when I am holding these cameras,” Pierce said. “It was cameras like these that allowed early photographers to take images of the United States, whether it be Yosemite or Yellowstone, and share those images with the world.”

At the behest of Pierce and his wife, Sharon Moore, his broad collection of photographica has been moved from a crowded room in their Arizona home to the California Museum of Photography where it will be accessible to both researchers and visitors.

“Larry’s collection helps trace the history of photographic technology through some crucial decades,” Gleason said. “The entire collection will be available for research, including the cameras, all the accessories and cases, as well as all the catalogs that Larry has given to us, so people can come and look at this material and study these details and differences for themselves.”

An exhibition of the collection is scheduled to open in the summer of 2019 after which the cameras, catalogs, and related materials will be available to view by appointment at the museum.

“My wife and I decided to donate this collection to UCR ARTS because we knew there was a museum here that was trying to tell people a story about photography,” Pierce said. “I think it’s a really good fit for us and for UCR. The museum will preserve them better than I could.”